By Rebecca Solnit

“In the past, it was racists and homophobes who attacked newcomers to San Francisco. Today, anti-tech activists are promoting a new nativism, charging incoming tech workers with undermining the city’s traditional values,” wrote Randy Shaw recently in a not-very-subtle ultimatum: love the massive new tech population and its impact on our city — or be compared to Bad People. But San Francisco’s history, though brief, is still varied enough that you can find any example you like. Including a lot in which new arrivals weren’t welcome for very good reasons.

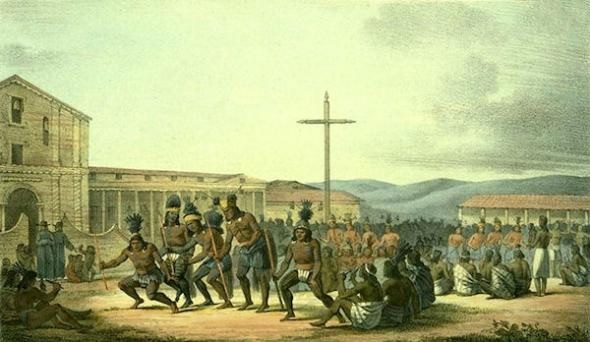

Let’s start at the beginning of the recorded history of what the Spaniards dubbed la Bahia de San Francisco, San Francisco Bay (the city didn’t get its name until much later). Relative newcomer (from Mexico City) and magnificent community member Adriana Camarena recently wrote about what may have been the first encounter between really really native San Franciscans and Europeans in her Unsettlers project:

“Ocean fog protected the Bay from European discovery, until 1769, when explorer Gaspar de Portolá viewed the body of water from a mountaintop. Six years later, on August 5, 1775, the ship San Carlos sailed through the golden gate under a moonlit sky. The Huimen Ohlone awoke to find a 193-ton, two-masted brig, 58 feet in length, floating in their landscape. In the following days, the crew of the San Carlos set out to sound the Bay in their longboats. Second Pilot Juan Bautista Aguirre took a boat Southeast to scout for good anchorage.

“On an inlet of a cove, he observed three native people weeping; their faces painted black and streaked with tears…. That day, we do not know for whom cried the Ohlone, but impressed, Second Pilot Aguirre named this cove after them La Ensenada de los Llorones or the Cove of Weepers; later to be renamed Mission Bay. On that day, the watershed of the Mission was first christened by the Spaniards in the name of tears.”

You could be fanciful and imagine they were weeping for Mission Bay itself, due to be filled in with garbage, sewage, rubbish, and sand from leveling the dunes nearby to develop the South of Market area. The new-made land housed the great railroad and terrible political power known as the Southern Pacific , then the huge biotech complex that is a triumph of Willie Brown’s manipulation of San Francisco demographics and economics and the biggest single development in the city’s history. Or you could imagine that the Ohlone were weeping at the arrival of the Europeans who would dispossess them of their land and attempt to annihilate their culture and, to a fair extent, their existence. Though there are still Ohlone here, who would still like some of their land back.

One Ohlone descendant, Andrew Galvan, recalls that in 1806, among the indigenous people in what would become San Francisco, “Out of a population of 850 people, 343 died of measles in a period of 36 hours. Every child under the age of five died.” Measles came with the newcomers, and along with the pretty marked graves with Irish and Spanish names in Mission Dolores Cemetery are the unmarked graves of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Ohlone people. Though probably delighted by some of the technology of the newcomers, they were not, so far as we can tell, thrilled by the newcomers themselves.

We don’t blame them for not being thrilled. Not all newcomers come with their hat in their hand, humbly, to learn the ways of the people there and meld with the existing culture.

In 1846, Captain John C. Fremont of the American Army came into Mexican California and began a campaign of murder and plunder known as the Bear Flag Revolt. It merged with the larger war on Mexico, by which the United States stole Mexico’s northern half and turned most of the Euro-Mexicans living here into a dispossessed underclass. Though the Californianos were legendary for their hospitality, they were not delighted by the arrival of the shabby, rag-tag, mixed-bag of an army Fremont and his gang assembled. “A marauding band of horse thieves, trappers and runaway sailors,” one witness called them.

General Mariano Vallejo himself recalled in later years ‘the vandal-like manner in which the ‘Bear’ soldiers sacked the Olompalí Rancho [just north of modern-day Novato on the Marin/Sonoma border] and maltreated the eighty year old Damaso Rodriguez Alférez, whom they beat so badly as to cause his death in the presence of his daughters and granddaughters.” The Californios were not pleased by this. Nor were they happy to be shot at, taken prisoner, or stripped of much of their land. We don’t think of them as impolite for not welcoming the invaders.

San Francisco got its name a few years later, as the sleepy hamlet of Yerba Buena exploded into the capital of the west and the gold rush. Hordes poured in, and it was those gold-seekers spreading into the hitherto-unviolated homelands of the foothill and Sierra tribes of California who committed, by sheer brutality and by numbers, and by ecological devastation, and by plan, the worst genocide in our state’s history. It’s in that decade, more than any other, that the rich, diverse native nations were devastated.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

Shaw points out the Chinese weren’t welcomed. My friend Philip Fradkin, in his magesterial history of the 1906 earthquake, writes of how the epidemic of bubonic plague a few years before was used by Mayor Phelan as an excuse to call “for the razing of Chinatown and the removal of its inhabitants to detention centers on either remote Mission Rock or Angel Island in the middle of the bay.” But there were still Chinese immigrants and Chinese-Americans in the neighborhood when the 1906 earthquake happened, and some of the city fathers used it as an excuse to try to eliminate Chinatown all over again.

It wasn’t about newcomers and oldtimers as it was about the powerful versus the vulnerable—though the powerful wanted to get rid of the oldtimers to move newcomers, as residents or businesses, into that prime real estate in downtown San Francisco. But the intended victims weren’t helpless: the Chinese government and various other forces helped them fight back. Chinatown still stands where it always has.

South of Market and the Fillmore don’t, however: Both buildings and inhabitants were eliminated in a furious project of “urban renewal,” the official name for a kind of 1950s-1970s urban cleansing that drove poor people and people of color out of their neighborhoods nationwide and rebuilt them according to the lights and at the service of the powers that be. This wave of erasure preceded gentrification—and like gentrification was often hailed at the time as an improvement on the old neighborhood.

But it didn’t improve it for the old neighbors; they were thrown out like trash in many cases, and new populations were brought in, or new regimented developments replaced the old independent space. I remember when the Fillmore’s vacant lots were finally filled in in the 1980s, decades after the beautiful, shabby Victorians there were razed. In between: vacant lots. With cyclone fences around them. In what had been the Harlem of the West.

Just this month, residents of the Fillmore Center’s high-rise towers, completed in 1991, were saved from having their homes turned into condominiums and sold out from under them. You could call this a way of not welcoming the newcomers who would have undoubtedly snapped up those condominiums as they have thousands of apartments from which tenants have been unwillingly removed, but you probably wouldn’t.

The old South of Market that had been safe harbor for generations of the poor, and was, even into the 1970s, a haven for old waterfront workers living in the neighborhood’s numerous residential hotels on small pensions and Social Security, was destroyed to make the shiny, amnesiac, upscale commercial-and-cultural place you probably know. Those old men, union men, organizers, survivors of the 1934 General Strike, knew how to fight, and fought a fierce, protracted battle. The monuments to their wills are the nonprofit highrise housing for seniors still in the neighborhood, among the parking garages and museums and mall-like complexes. But San Francisco became a harder place in which to be a poor person.

Newcomers—refugees from conservatism, from homophobia, from small-town intolerance, from the dirty wars in Central America in the 1980s and the Jim Crow south of the 1940s and 1950s, seekers of education, liberation, social experiments, and cultural possibilities—have arrived here mostly as trickles, not floods. They’ve become part of the city, often its heart — its muralists and its Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, its poets and professors and doctors and dreamers. But that’s not the only history of San Francisco. As Shaw well knows, there is another history, the history I’ve been relating, of invasion and eviction and evisceration. It didn’t stop with the Ohlone or the Californios or urban renewal.

You welcome guests into your home. But when people are trying to push you out of your home, they don’t exactly count as guests. So although many individuals in the new tech population are undoubtedly lovely — the ones who aren’t putting out screeds against the homeless, misogynist rants, paranoiac comparisons of San Franciscans and tech critics to Nazis, or pushing their Google glasses in your face — this huge and hugely well-paid population is displacing a lot of us. Or rather, they are giving landlords and speculators and lawyers a reason to evict, by Ellis Act, by threat and intimidation, by other means, many longtime residents, by being very willing to take their housing and pay exorbitantly for it (and occasionally doing their own owner move-in evictions).

The evicted include vulnerable residents—the ill, the elderly, the economically fragile. And important contributors to San Francisco’s culture—poets, teachers, human rights activists. The epidemic of evictions threatens to change the culture of San Francisco or just evict it, as downtown galleries, social organizations, longtime neighborhood bars, affordable housing, and the vision of a city where you can live for something more and other than working 60 hours a week for a megacorporation, are all driven out.

So the incoming tech population, as we all already know, is contributing to making life really hard for a lot of San Franciscans—those who have been evicted, who fear eviction, or who just see a lot of what they love being thinned out and dying off and maybe even looking doomed. This is what’s not being welcomed.

And Randy Shaw knows it. It’s thanks to his work in earlier decades, and that of other activists, that so much of the Tenderloin is protected as nonprofit housing. People aren’t being driven out there—though a crazy tech flophouse called the Negev is nearby, renting beds in dorms for $1,000 apiece.

Here’s what I’m not welcoming to San Francisco. The eviction of a friend’s mom who stood out in the rain at a demonstration a week or so ago, holding a sign that said, “I am a senior evicted from my home of 36 years.” The eviction of Rene Yanez ,who did more than anyone to make the Mission the rich Latino cultural center it’s been for forty years—evicted he and his wife both had cancer. The eviction of my friend Aaron Shurin, the great poet of gay life here and a witness to it since the mid-1960s. The pricing-out of Esta Noche, the Latino drag queen bar, so that San Francisco can have yet another cocktail lounge for straight white people who already own most of the turf in this country and don’t really need a few hundred square feet more.The driving out of a host of nonprofits serving human rights, the environment, education, and more.

The eviction of the vehicularly housed from 61 new locations, announced just this week—and what does it mean that we are a city that has allowed corporate buses to crowd our public bus stops without payment or permission but won’t let the poor park their homes? Because this city is becoming a place that serves the affluent and does disservice to the rest of us.

When hordes of prosperous young white men piss all over Dolores Park, the city plans to build special urinals for them — while continuing to arrest homeless people even for sitting or lying in public, let alone urinating. (Even muralist Megan Wilson, who has given so much to this city over the past couple of decades, was threatened with arrest when she sat down to rest while painting a mural on Clarion Alley.) Because the welcoming city Shaw speaks of is itself being evicted. And being replaced by some form of gated community. We’re going from inclusive to exclusive.

This city’s history begins with weepers. Maybe it’s ending that way too, or at least an era is. But the real issue is why Randy Shaw is telling people how to feel rather than addressing why they feel that way. And why he’s portraying as the victims in this confrontation the powerful newcomers who are displacing longtime and often more vulnerable and diverse (in age, race, class, vocation, and income) residents.

Diane DiPrima, who was a newcomer to this city forty years ago and who is counted as one of the great poets of her generation, wrote a very short poem a long time ago. It goes like this: “Get your cut throat off my knife.” It’s spoken in the voice of the attacker, and it’s the very essence of blaming the victim, of mixing up what’s happening, of denying who has the power. Which is why it’s called “Nightmare 6.” I hope San Francisco will live to harbor more generations of great poets, but right now things aren’t looking bright in that respect.

And there isn’t an app that’s going to fix it. Welcome to Nightmare 2014.