Nicole has resorted to storing her wages in an office desk drawer at her place of work after funds she was saving for a rental deposit were garnished from her checking account for child support.

Due to the deceptive mortgage loan Teresa was sold, which she thought was a fixed rate, she was forced to sell the home she had inherited from her grandmother. Amanda was receiving on average 50 phone calls a day from debt collectors demanding payment. After taking out a payday loan, Dominic ended up paying over twice his original loan.

These are four real stories I learned about during my research on how the financial services industry is exploiting consumers in San Francisco.

Consumer financial protection is a 21st-century civil rights issue. These protections are regulations thatprotect consumers from unfair, deceptive, or abusive financial products and services. They favor the consumer over the financial services industry. The financial services industry comprises a widerange of businesses that manage money,which include banks,credit unions, and credit card companies, as well as more nefarious companies such as debt collectors, payday lenders and check cashers.The industry controls many aspects of people’s lives — from the ability to access credit, to cashing a paycheck, to keeping their homes, and everything in between. Consumer rights are vital for protecting and building financial assets, particularly for low-income communities, people of color, the elderly, and immigrants.

In response to the 2008 financial crisis, the Obama administration created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the federal agency responsible for protecting consumers from abusive, deceptive and predatory practices of the financial services industry. The CFPB’s Consumer Complaint Database has been an important resource for the American public for the past seven years. The Consumer Complaint Database is a publicly available collection of complaints made by Americans across the country on a range of consumer financial products and services.

This tool has helped to enable the bureau to recover more than $12 billion in relief for almost 30 million consumers and identified bad actors of the financial services industry.[1] For example, the database was instrumental in revealing that Wells Fargo opened 3.5 million fake accounts without consent of its customers.[2] This data has also been harnessed to create stronger consumer financial protections and increased regulations that promote industry accountability.

There is very limited data to describe the specific problems San Francisco residents face with financial products and services. This deficit creates difficulty for city policymakers to accurately identify the trends and agents responsible for financial practices causing harm specifically in San Francisco. One resource that has yet to be fully leveraged is the Consumer Complaint Database, which has almost 3,400 consumer complaints filed by San Francisco residents.[3]

Unfortunately, recently there has been an alarming rate of deregulation of consumer financial protections at the federal level by the interim acting director of the Bureau, Mick Mulvaney, who was appointed by Donald Trump last November. Consumer advocates are extremely concerned that the Consumer Complaint Database may not survive the Trump era of the Bureau’s leadership.[4] In April 2018 those fears were realized when Mick Mulvaney suggested that he might remove the databaseof complaints to the agency from public view.[5]

In June, the White House nominated Kathy Kraninger to succeed Mulvaney to lead the CFPB. She reported to Mick Mulvaney at the Office of Management and Budget and managed the budgets for the Department of Homeland Security. If confirmed, Kraninger would lead the CFPB for a term of five years and it is believedshe will attempt to execute Mulvaney’s plan of taking down the Consumer Complaint Database from public view.[6] Kraninger’s nomination was postponed earlier this month by the Senate Banking Committee after Democrats questioned her lack of experience in financial regulation and her role in executing the “zero-tolerance” policies that have led to thousands of immigrant family separations.[7]

I asked Deborah Jackson, who works on financial empowerment programs for the San Francisco Housing Development Corporation, about what effect the removal of the database would have on the communities SFHDC serves, who predominantly live in Bayview-Hunters Point, the Western Addition and Potrero Hill. She said, “we already are dealing with an overwhelming problem in the Bay Area with uninformed people, and the possibility of them being ripped off more, without any recourse, will be greater.”

Given the precarious fate of the CFPB Consumer Complaint database, I conducted the first deep data analysis of the 3,400 public complaints filed by San Francisco residents. With an estimated 353,287 households living in San Francisco, these complaints provide a robust sample size to understand some of the financial struggles of the wider population of the city.[8] My research highlights how predatory financial services are a citywide problem: San Franciscans living at every income level and in every part of the city are struggling to resolve their financial issues with the wolves of Wall Street, the financial services industry. Putting this revelation in context of what’s happening at the national level, cities like San Francisco need to step up where they can to take the place of the federal government and provide consumer financial protections and education for city residents.

What the data tells us

As of March 1st, the Consumer Complaint Database had collected a total of 978,213 complaints. Californians had 137,701 complaints published, and 3,390 of those complaints have been submitted by San Francisco residents.

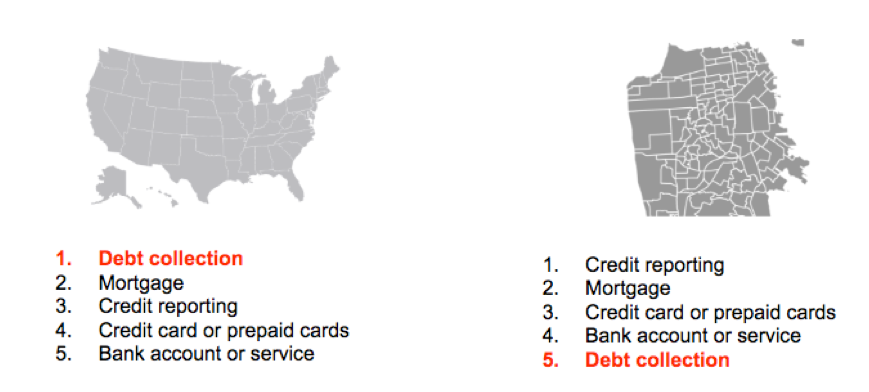

Fig. 1. The top five product complaints at the national level and at the local level between December 2011 and March 2018

The product complaints at a national level do not mimic the complaints at the local level. It’s important that city policymakers are aware of the unique financial challenges in San Francisco, so they can create policy and programs that address the distinct issues local residents are having with financial services and products. Additionally, if city policymakers are unaware of these nuances, they could be developing policies and prioritizing programs that don’t actually address the specific needs of San Franciscans.

The broad range of complaints about financial products and services speaks to the diversity of the consumers themselves. Different types of consumers use different types of financial services and products. Although the database doesn’t collect information on the consumer’s race or income, we can nonetheless make certain inferences about who the consumer might be, as demonstrated with a few examples. For instance, a mortgage complaint would come from someone who is a homeowner, who, according to Prosperity Now’s 2017 Scorecard, makes up 36 percent of the San Francisco population. A debt collection complaint would come from someone who is behind on bill payments and is likely struggling financially. Someone complaining about a payday loan is underbanked, meaning that they might have a bank account but use other alternative high-cost services to meet their financial needs.

The same Prosperity Now report found that 16.9 percent of San Franciscans are currently underbanked. Complaints about money transfers or virtual currency include remittances, a service that is used by immigrants who send money back to their home country. Assessing the different types of products and services San Francisco residents demonstrates the diversity among the consumers going to the CFPB for help.

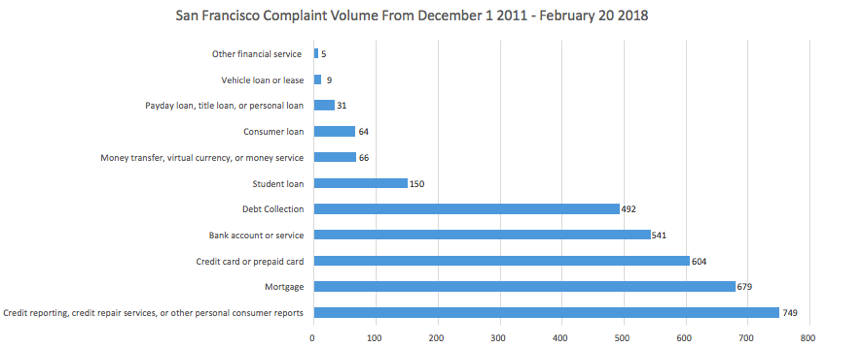

Fig. 2. The number of published complaints submitted by San Francisco residents to the CFPB organized by product

Most of the consumer advocates and direct service providers I interviewed were surprised that payday loans were not ranked higher. Mohan Kanungo, director of programs and engagement at Mission Asset Fund, suggested that this might be due to the fact that the payday lending industry is highly regulated in San Francisco.[9] Ernesto Martinez of Mission Economic Development Agency reacted to the data findings by saying that he thought payday lending, check cashing and money transfers seemed underrepresented from this data set.Both agreed that it is highly likely that lower-income, non-English speakers are less likely to submit a complaint to the CFPB.

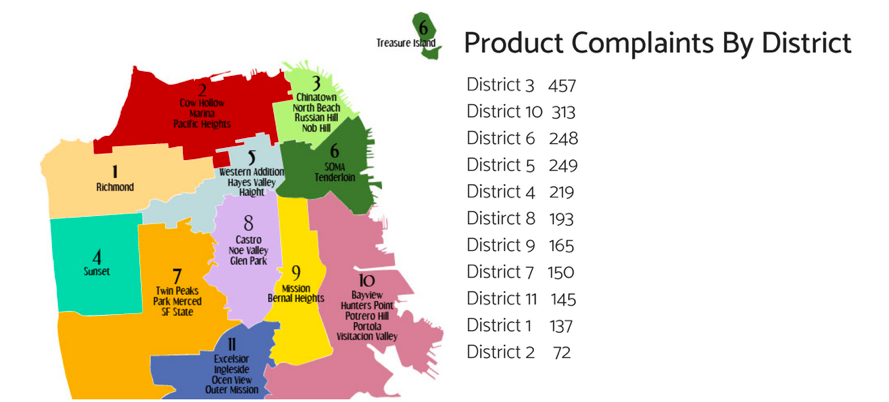

Almost 70 percent of the public complaints were associated with a specific San Francisco area of the city. The top five neighborhoods that submitted complaints to the CFPB were Nob Hill (189), Inner Mission / Bernal Heights (165), South of Market / Downtown / Civic Center (152), Ingleside-Excelsior / Crocker-Amazon (145) and North Beach / Chinatown (145). A majority of the 22 neighborhoods had roughly the same amount of complaints: the median of the data set was 109.5 complaints and the average was 106.9. This shows that problems with the financial services industry are widespread and not concentrated in certain areas of the city.

Fig. 3. San Francisco complaints organized by district[10]

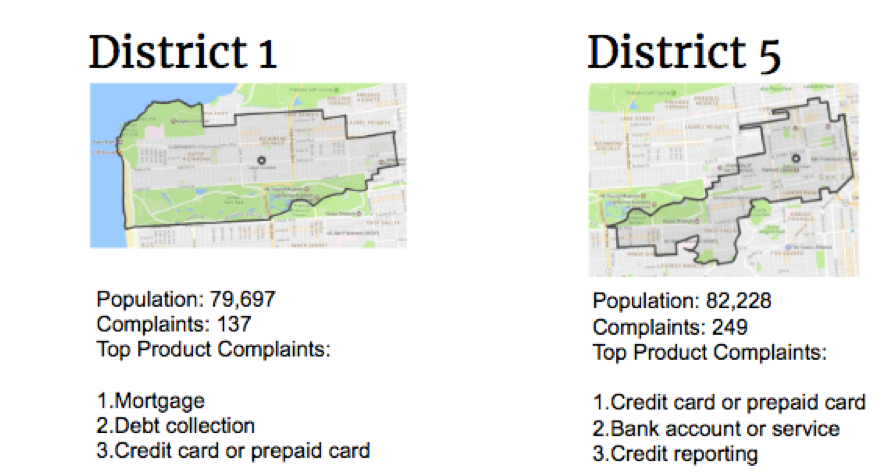

Breaking the data down by district highlights the fact that complaints can vary by district. For the purposes of this article, I compared my district, District 1, to District 5. As you can see, the two districts have similar population sizes but District 5 has double the amount of complaint. Their respective top three product complaints are also very distinct.

Fig 4. Comparison of top three product complaints for District 1 and District 5[11]

This finding should be used in three powerful ways. First, the information can help inform each district supervisor of the specific issues with which their constituents struggle with. Second, the finding will help them assess the proper actions to prioritize in an effort to help their residents resolve issues with their financial products and services. This information can also help policymakers develop better curated consumer education for different areas of the city, and provide that information to their partner agencies who are involved in financial empowerment integration.

The limitations of the database

There are a number of limitations to the database. Although it’s another valuable resource the city should use to inform its local consumer financial protection policies, the database should not be viewed as the sole means for having a comprehensive understanding of all the major consumer harms experienced by the entire San Francisco population. By understanding the database’s limitations, we can then propose how to find supplemental information to fill the identified gaps.

Unfortunately, many consumers haven’t ever heard of the CFPB, much less that the database exists. Many low-income people who are working multiple jobs just might not have the time to submit a complaint. This is where the data might be skewed, with an overrepresentation of complaints from wealthier individuals. However, this research can only make intelligent inferences because income is not a piece of data the CFPB collects when a consumer submits a complaint to their database.

Since the CFPB doesn’t track race, gender or income, this study is limited in better understanding who is represented in these submitted complaints.

Two demographics who are likely to be severely underrepresented that were mentioned in my interviews with community non-profits were the homeless population and immigrant communities. Jennifer Friedenbach of the Coalition on Homelessness told me that because many people who are experiencing homelessness are most likely living in crisis, they probably only have the mental bandwidth to focus on their immediate needs and don’t have the wherewithal to submit a complaint.

There are two major reasons why the immigrant population might be underrepresented in the data. First, the public complaints on the CFPB website are only viewable in English. This might be a huge problem because according to the US Census, 44 percent of people living in San Francisco speak a language other than English at home.[12] A consumer can call the CFPB, and help is available in 180 languages but only 6 percent of consumer complaints are received via telephone calls.[13]

Secondly, given the Trump Administration’s xenophobic rhetoric and harsh stances on immigration, immigrants, especially the Latino community, are fearful to access any type of government resource or take advantage of any legal rights due to the threat of deportation.

Lastly, given that the CFPB’s Consumer Complaint Database has transitioned from a pro-regulation and pro-consumer administration to a deregulation and pro-industry administration, it’s also important to think about how many San Francisco residents have not submitted complaints because they didn’t believe or trust the Trump administration would do anything to resolve their issue. It would be difficult to quantify this number, but it will be interesting to see if the number of complaints filed in 2018 fall now that the CFPB is being led by the Trump Administration, who is focused on defanging the entire agency.

What should the city of San Francisco do with this data analysis?

The federal government is quickly absolving itself from the responsibility to protect consumers from the wolves of Wall Street. Local governments should not stand idly by when the Trump administration is creating an environment that will enable the financial services industry to once again abuse consumers without any major repercussions. Luckily, San Francisco is taking proactive actions to develop its own local consumer financial protections, and they will need to leverage all the data and resources available to create policies that address the specific needs of their city residents.

My recommendations

All relevant city stakeholders should review this research’s findings to inform the direction of the city’s local consumer protection policy

This data analysis can be used to help improve existing programs,develop future policy and share information with community partners.The findings that surfaced from this research should interest a variety of stakeholders which include: Mayor London Breed and the Board of Supervisors, the Office of Financial Empowerment, and other city departments that are relevant to consumer protection or are interested because of how it affects their constituents. For example, given that mortgages were consistently a top consumer complaint, this data should be shared with entities like the San Francisco Housing Authority and the Mayor’s Office Of Housing and Community Development. The City Attorney’s Office and the District Attorney’s office might be interested in specific companies who have harmed San Francisco residents and would be able to pursue legal action against the bad actors. Given that economic inequality is a major campaign topic, city candidates running in the November 2018 should be aware of the consumer financial harms happening in the city and in specific districts, especially given the product complaint differences across the districts. Industry experts, non-profit partners, and consumer advocates should also be interested in these findings as they develop strategies in the Trump era.

- San Francisco should develop a Consumer Bill of Rights

The reality is that many consumers don’t know all of their rights. This paces them at high-risk of getting taken advantage by the financial services industry, which could result in devastating and debilitating consequences. The bill of rights could be passed by the Board of Supervisors and it would outline the rights related to the financial services industry that consumers already have. Such rights could be taken from both state and federal law in order to avoid preemption. The bill of rights should be written in plain language that is easy to understand and made available in many other languages besides English. The San Francisco Consumer Bill of Rights should be showcased on various city departments’ websites and shared electronically and on printed material with community partners and other relevant stakeholders.

- City Hall should commission a household level study to obtain more qualitative information about the financial struggles of San Franciscans, particularly low-income communities and families of color

As mentioned, the limitations of the CFPB Consumer ComplaintDatabase seem to suggest that there might be overrepresentation of middle to high-income consumers, and an underrepresentation of low-income consumers. We also don’t know other important information about the consumers (ex. Race, gender, employment status, level of education) that would be very helpful to know. A household level study would complement the data findings to help reveal how consumer harms are impacting real people’s lives. It would also be able to demonstrate the intersectionality of the consumers who live in San Francisco and are experiencing problems with the financial industry. For example, a consumer might be a low-income immigrant who predominantly speaks Spanish and had a problem with a money transfer. The household level study would further humanize the problems San Franciscans are having with predatory financial practices.

- The methodology of this report should be shared with other cities around the country so they can utilize the CFPB Consumer Complaint Database while it’s still available to the public

Other cities should be contacted and notified about the precarious fate of the CFPB Consumer Complaint Database and be strongly advised to download their city’s information so they can conduct their own analysis of the consumer financial harms affecting their residents.

Moving forward

Given that the CFPB Consumer Complaint Database is a relatively new resource that many people are not aware of, it’s striking that almost 4,000 SF residents have filed a complaint to the CFPB in an attempt to get a response from the company and resolve their issues. If this many people were able to find the Consumer Complaint Database and were upset enough to take the time to file a complaint, how many other city residents are struggling alone with their financial company?

We are living in a time where consumer financial protections cannot be taken for granted; they must be fought for. It’s clear that for the foreseeable future we cannot depend on the leaders in Washington to hold the financial services industry accountable. Instead, it will be up to progressive cities like San Francisco to remain fierce champions of consumer financial protections; people’s lives depend on it. Jessica Lindquist received her Master’s degree In Public Affairs from the University of San Francisco in May. This article is adapted from her Capstone thesis.

[1]Kathryn Vasel, “The CFPB’s Giant Database of Consumer Complaints,” CNN Money, November 27, 2017, https://money.cnn.com/2017/11/27/pf/cfpb-database-complaints/index.html.

[2] Jackie Wattles et al., “Wells Fargo’s 17-month Nightmare,” CNN Money, February 5, 2018,

[3] “The Consumer Complaint Database,” The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, accessed March 1, 2018,

[4] Wendy Brown, “Undoing Democracy: Neoliberalism’s Remaking of State and Subject,” in Undoing the Demos(New York: Zone Books, 2015), 27.

[5] Sylvan Lane, “Acting CFPB Chief Mulls Taking Down Public Complaint Database,” The Hill, April 24, 2018, http://thehill.com/policy/finance/384697-acting-cfpb-chief-mulls-taking-down-public-complaint-database.

[6] Irina Ivanova, “How Kathy Kraninger Plans To Run The Consumer Financial Protection Burea,” Money Watch, July 19, 2018, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/how-kathy-kraninger-plans-to-run-the-consumer-financial-protection-bureau/.

Debbie Goldstein, “Would Trump’s CFPB Pick Silence Consumers?” American Banker,July 20, 2018, https://www.americanbanker.com/opinion/would-trumps-cfpb-pick-silence-consumers.

[7] Neil Haggerty, “Panel Vote On CFPB Nominee Delayed As Senate Plans To Recess,” American Banker,August 1, 2018.

[8] Prosperity Now, “San Francisco County, CA Prosperity Now Scorecard 2017.”

[9] In May 2008, the city worked with the Planning department to pass the “Fringe Financial Service Restricted Use District (Municipal Code section 249.35),” which prohibits new or relocating check cashers and payday lenders from six special districts, and prohibits them from within a ¼ mile of an existing fringe financial service.

[10] Map taken from here http://www.sfhomeblog.com/tag/chinatown.

[11] District information taken from here

[12] “Quick Facts: San Francisco County, California,” The United States Census, accessed April 24, 2018, .

[13] The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “2017 Consumer Response Annual Report,