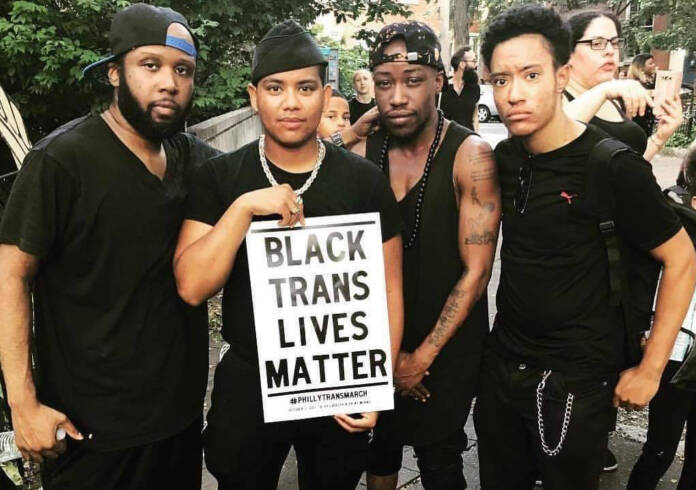

Black queer people exist. Stonewall was a riot against police. The fight for Gay Liberation was lead by queer and trans women of color. Why do we need to learn these things over and over?

June is Pride month, and the streets are full of protesters against police murder and for Black lives—never has the connection between queer and Black struggles for justice been more plain, even if the histories of both those struggles are very different. With Pride going virtual this year due to COVID, this month is an opportunity to reconnect with its radical roots, and stand up for Black lives.

It’s been heartening to see many commentators drawing a line from the direct action of the 1969 Stonewall Riots—a grassroots revolt against homophobic police violence which is celebrated annually as Pride—to the George Floyd protests taking place all over the country today, without erasing the tremendous work Black activists have done in the past.

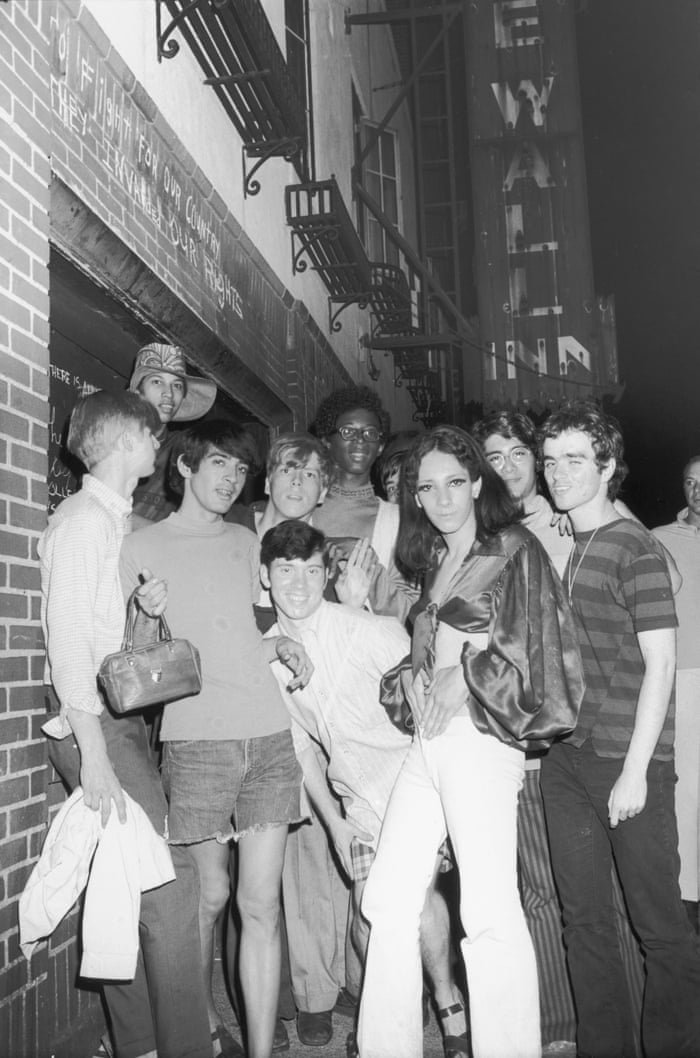

The uprising after a raid on the Stonewall Inn bar on New York City’s Christopher Street remains the default birth of the contemporary LGBTQ rights movement, far from finished, but considered a successful spontaneous uprising that changed the world for the better. It was a days-long conflagration, rowdy and celebratory, which brought a then-diffuse community under one banner to agitate for civil rights. Bars were graffitied, windows were smashed, businesses were damaged, and some stores were looted.

And while we will forever be arguing over “who threw the first brick at Stonewall” there is no doubt that one of the loudest voices right at the beginning was that of Black butch lesbian Storme DeLarverie, who may have thrown the first punch. The early Gay Lib movement was led by two emphatic and fabulous trans women of color who were at the riots, Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson. They didn’t advocate for the warm fuzziness of “equality,” with its comforting assimilationism in support of an immoral system, but the hard work and utopian vision of Liberation with a capital L for all people.

Future trans, AIDS, and prison justice leader Miss Major was also at the riots, and later brought that revolutionary energy with her to California. Here in San Francisco, we sparked our own queer rebellion three years before Stonewall. The 1966 Compton’s Cafeteria Riot in the Tenderloin was an uprising of trans woman and sex workers, Black women included, against police harassment and abuse.

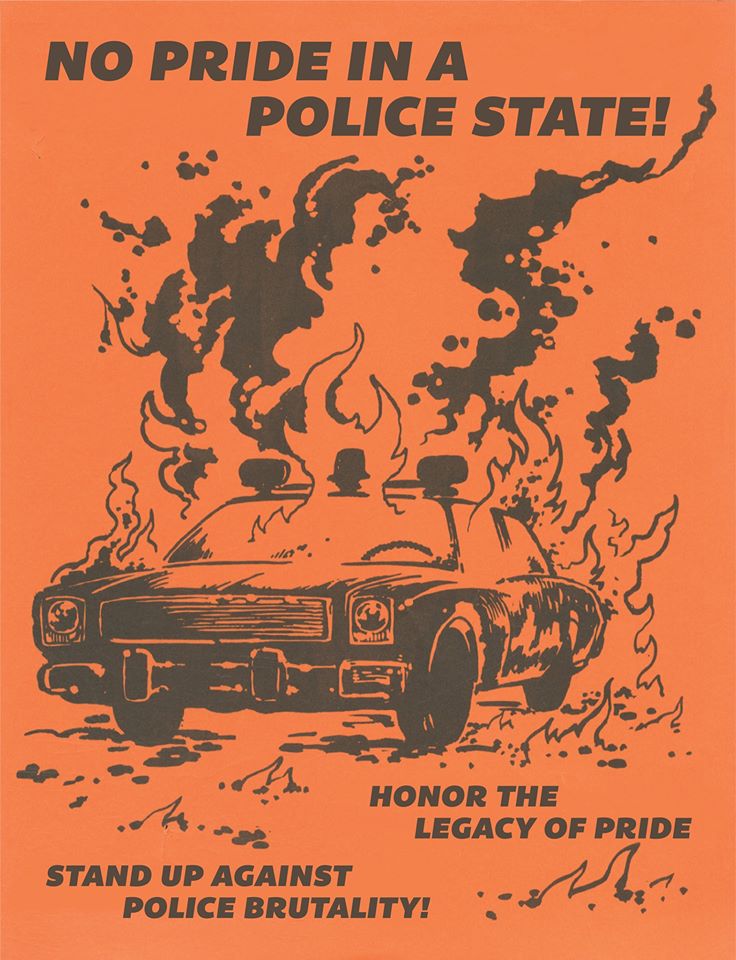

But it’s another, more violent, local revolt from 41 years ago whose memory has been revived as a queer correlation to the George Floyd protests. The White Night Riot—when cops descended on gay people in the Castro protesting Dan White’s conviction of mere manslaughter instead of murder for killing Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone—is being talked about more than I’ve ever heard before, and by mainstream media figures. On May 21, 1979, SF gays fought back after being beaten down, burning police cars, smashing storefronts and City Hall windows, and blocking streets. “No Apologies!” was the rallying cry.

Searing images of the White Night Riot, paired with scenes of radical resistance from ACT-UP and other AIDS activists, have been making the rounds on social media, helping to connect today with yesterday. And an inspiring wave of queer Black activists who have inherited that spirit, like Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza and Transgender Cultural District co-founder Honey Mahogany, have been leading us onward.

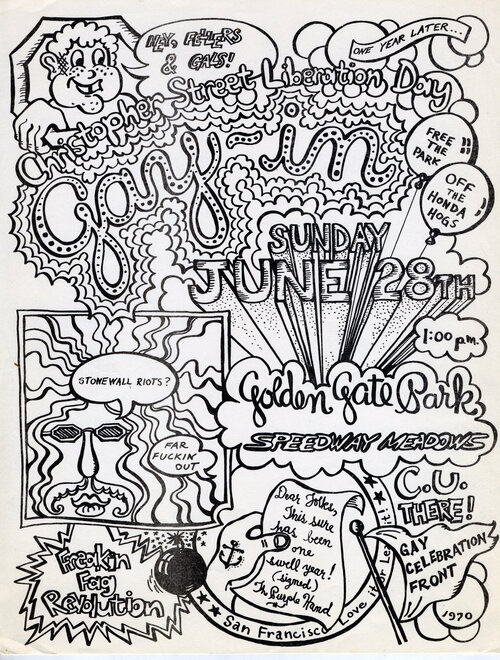

So why is this queer history of violent police resistance and Black and trans leadership continually erased in the popular image of Pride? It has a lot to do with its history of commercialization. Pride, of course, hasn’t always been about corporate sponsorship and glitzy floats leading thousands in matching company logo t-shirts up Market Street. It used to be authentically freaky and homespun, a potluck with sly intentions. As latest GLBT Historical Society Museum and Archives newsletter “How was Pride born?” puts it:

“It all started with an impromptu march and a picnic. On June 27, 1970, a small band of hippies and ‘hair fairies’ marched down Polk Street, then San Francisco’s most prominent LGBTQ area, to celebrate an event they called ‘Christopher Street Liberation Day.’ The following afternoon, some 200 people congregated for a ‘Gay-In’ picnic in Speedway Meadows at Golden Gate Park. These two modest gatherings inaugurated the annual celebration we now know as San Francisco Pride.

“As difficult as it is to believe that every single Pride participant in 1970 could fit into a small area of the park,” the newsletter continues, “it’s also remarkable that just 10 years later, Pride was drawing some 250,000 participants and spectators.” (The Society’s online exhibition “Labor of Love: The Birth of San Francisco Pride 1970–1980” opens June 15.)

This phenomenal growth attracted money and power. For a while, seeing corporate participants and sponsors declare themselves gay-friendly, and witnessing workers step out in public as queer, felt truly liberating. The police want to march with us instead of beat us? Wow, neat, even if they arrest us later for cruising in the bushes.

Increasing commercialization was a trap, though, transforming Pride into a marketing opportunity: Corporations have to target consumers—mostly straight, white, middle class—and guard their “neutral” brand image. Cries to tone down our radical, sexual, and diverse past often came from white gay men themselves, terrified of losing a growing grip on mainstream acceptance.

Thus Pride gradually became the weirdly sanitized spectacle it is, a Disneyfied White Party in the public mind’s eye, albeit one where young queer people can still encounter others like themselves, strange magic can happen, and older people can find community. (I cry every year at the PFLAG contingent, come on.)

And even though corporations need us now way more than we need them, Pride may be unable to escape their strangling, rainbow-feathered embrace. Earlier this year, I attended a meeting of the new Pride Board of Directors intended to address a non-binding vote from Pride members to ban Google and the Alameda Sheriff’s department from participating in the 2020 event.

Google was in the hot seat for its lax policy around homophobic YouTube harassment and resistance to workplace organizing. The Alameda sheriffs, who had never marched in the parade, were being spotlighted due to of their militarized crackdown on Moms4Housing, a group of homeless Black women who had occupied a vacant home in Oakland. (The police in general were also on the outs for arresting protesters who blocked the 2019 parade, who were calling for, yes, an end to police and corporate involvement in Pride.)

Board President Carolyn Wysinger declined to implement the vote due to its non-binding nature and “legal and financial concerns”—including the possibility that Google might sue the Board members themselves. Wysinger described the vote as a perilous move that could endanger her as a Black woman who was herself experiencing homelessness, which demonstrates how racial and housing injustice block advancement on all sides. The sheriffs issue was left unaddressed.

The whole matter was made moot when COVID forced Pride to move online, but Google was recently exposed as rolling back diversity initiatives to please conservatives and cops are out here teargassing people as they protest for Black lives. Groups like Gay Shame, which have creatively protested the commercialization of Pride for years, could have seen that coming. But watching a proposed experiment to wield Pride’s power for social change being quashed by a potential corporate threat was chilling.

My hope is that Pride going virtual for its 50th anniversary may be just the reboot we need to re-engage with its original spirit, minus the Mentos floats and Lite Beer banners. While we’re fighting against a pandemic virus that very much triggers AIDS trauma, in a country that still endorses public, extra-judicial executions of Black people in the name of “law and order,” we need to channel our inner irascible Larry Kramer (RIP): Get out there, put our (masked, socially distanced) bodies on the line for Black people, and be totally loudmouthed pains in the ass for justice.