By Zelda Bronstein

SEPTEMBER 18, 2014 — There’s lots of news on the light industrial/PDR (Production, Distribution, and Repair) front.

- On September 9, District 6 Supervisor Jane Kim introduced a bill that would prohibit office or residential conversions of property zoned for light industry, a.k.a. PDR in the Central SoMa (né Corridor) Plan area for 45 days

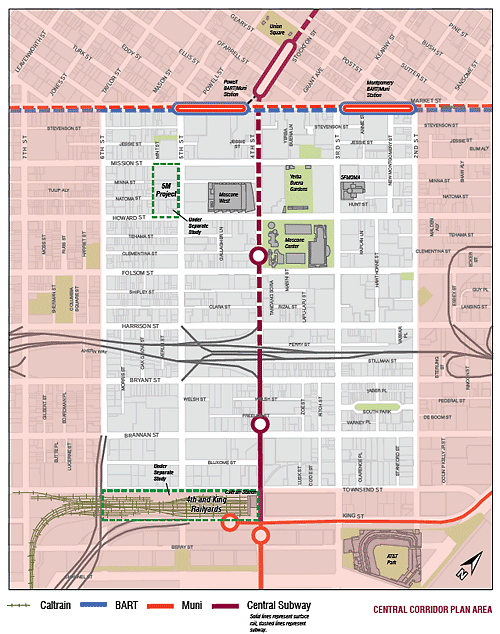

Bounded by Market St. on the north, 2nd St. on the east, Townsend St. on the south and 6th St. on the west, the plan area lies wholly within District 6.

Stating that “recent economic trends,”—“the current economic boom cycle” and associated “development pressure”—are making PDR-zoned property “particularly susceptible to displacement and outright loss,” the bill seeks “to provide stability to the neighborhood during the time that the draft Central SoMa Plan is under development and public.”

The intention is admirable. As always, however, the devil is in the details. A few questions, then, about some of the bill’s details:

Since the plan isn’t going to come before the Planning Commission, much less the Board of Supervisors, until 2015, why is the moratorium initially proposed for only 45 days? The section in the city’s Planning Code, 306.7, cited in the bill, says nothing about a 45-day maximum for the initial duration of interim zoning controls.

Kim aide April Veneracion Ang explained to me that because the interim controls involve a prohibition on development, they fall under State law, specifically, California Government Code Section 65858, which stipulates the initial 45-day duration. That law provides for extensions up to a year.

“Our intention,” Veneracion Ang said, “is for the interim controls to be in place until the Central SoMa Plan is adopted.”

Another questionable detail: The bill exempts six unspecified projects from the moratorium. What are those projects, I asked, and why are they being exempted?

Veneracion Ang told me that her office made “a policy call” based on recommendations from the Planning Department to exempt projects that are

— “in the pipeline”—specifically, that are on the list of “pending” developments and, in the case of the office projects, that had submitted an Environmental Impact Report, or

— in zoning districts that permit residential and office development.

Five of the six meet those two criteria:

— 363 6th: a 12,396 sf industrial building proposed for demolition, to be replaced by an 8-story, 85-feet tall mixed use building that includes 64 dwelling units, 30 parking spaces, and 2,332 sf of commercial space on Sixth Street, MUR (Mixed Use-Residential district)

— 255-259 Clara: a one-story, 5,622 sf industrial building proposed to demolition, to be replaced by a 5-story residential building with 8 dwelling units and nine parking spaces, MUR

— 750 Harrison: a one-story, 5,324 sf commercial building, currently occupied by a nightclub, Manor West, proposed for demolition, to be replaced by an 8-story, 75-foot tall, 43,067 sf mixed use building that includes 77 Single Room Occupancy dwelling units, one parking space, and 2,862 sf of commercial space, MUO (Mixed Use-Office)

— 938 Howard: a 25,500 sf, 1924 industrial building that is on sale for $4,975,000 or $195/sf, MUR

— 645 Harrison: a 148,076 sf, formerly industrial building that appears to have been converted into office space without permits that’s renting for at least $55/sf, SSO (Service-Secondary Office).

The parcel is included in a proposed, 1.3 million sf development that also encompasses 653 Harrison, 657 Harrison, 665 Harrison, and 440 Second St. and features a 478,000 sf office building, a 406,000 sf residential tower and a 300-room hotel.

The outlier is 660 3rd, which is, or more precisely, was—it was approved last Thursday at the planning commission—in the planning pipeline but in a zoning district, SLI (Service-Light Industrial), that generally prohibits offices. (More about 660 3rd below.)

The speculative frenzy

If it’s hard to see how exempting any property in the Central SoMa Plan area from the interim zoning controls could help stabilize the neighborhood, it’s impossible to see how exempting 938 Howard and 645 Harrison in could do so. If anything, both properties exemplify the current speculative frenzy. They also show how that frenzy is being juiced by the Planning Department.

The mega-project on Harrison would not be permitted under the current SSO zoning. The Central SoMa Plan would change that zoning to MUO. A more precise acronym would be AAG, short for Almost Anything Goes.

That’s only one of the many zoning changes in the plan, all of which would “upzone” the area, meaning that they would allow much greater heights and densities than existing zoning.

The city’s planners note that the project on Harrison even “exceeds the height limits” for the new plan’s taller, “proposed designations” But instead of recommending that it be scaled back, their “preliminary project assessment” finesses the problem:

While the proposed project’s height is greater than the proposed scenario, the Planning Department will analyze the project’s proposed height as part of the higher height limit alteration in the Central Corridor Plan EIR.

In other words, it’s not just “the market” or some invisible hand that’s driving up the real estate prices in Central SoMa and driving out the light industrial businesses and their blue-collar jobs. It’s the official policy coming out of the Planning Department and the mayor’s Office of Economic and Workforce Development.

Kim’s bill lists among “the primary objectives of the Central SoMa Plan…maintain[ing] the area’s vibrant economic and physical diversity.” Indeed, the Plan does claim to be fostering diversity. But that claim is belied by the effects of the zoning changes it envisions. The Central SoMa Plan itself states that the proposed new zoning will displace at least 1,800 blue-collar jobs with high-rent, high-rise office development, much of it designed for the tech industry.

Assuming this bill becomes law, the real question is: what difference is it going to make after the moratorium ends or even while it’s in force? The text reads:

The Board urges the San Francisco Planning Department to balance the need for retaining PDR with the desire to have more affordable housing, a vibrant small business community, and high density housing and office space in the future Central SoMa Plan Area.

Nothing in Planning’s recent history suggests that it is capable of achieving such a balance. On the contrary, the evidence indicates that the department regards the city’s light industrial economy as dispensable.

The impetus for retaining, protecting, and promoting San Francisco’s blue-collar businesses and jobs comes from the PDR community itself. The proposed legislation needs to specify a way that that community’s needs and advice will have to be taken seriously by the city’s planners.

- On September 12 attorney Andrew Junius attacked Kim for trying to stem the “inevitable” tide of gentrification

Junius took aim at Jane Kim in a post,“Back to the Future: South of Market Again the Target of Patchwork Zoning,” that appeared on the website of his law firm, Reuben, Junius & Rose.

There he accuses the supervisor of “opening Pandora’s box and restarting the debate [“over where to put PDR”] that took more than ten years to resolve the first time around,” and that “was supposed to have ended when the City adopted the Eastern Neighborhoods Plan” in 2008.

Junius claims that under the new rules,

significant areas of the City were down-zoned for the express purpose of saving space for PDR businesses….[There is almost no legal use of these PDR-zoned buildings other than light industrial activities. And PDR zones cover large amounts of area in Showplace Square, the Mission, Potrero Hill, and the Central Waterfront.[Curiously, he leaves out Central SoMa.]

The Eastern Neighborhoods Plan took a decade or more to finalize. While many people are not satisfied with how the Eastern Neighborhood Plan turned out (including, but not limited to, the property owners whose buildings were downzoned and are now vacant because of it), there at least seemed to be an understanding that this issue was settled. Apparently not.

In a marvelous display of incoherence, Junius continues:

As market pressure continues to build in San Francisco for available space of any kind for residential, office and other projects, Supervisor Kim steps into the fray to stem the tide that seems inevitable: the slow evolution of South of Market from a former industrial and warehouse district to a high-density, mixed office and residential neighborhood near transit and jobs.

So on the one hand the “issue” of “where to put PDR uses” was settled, but on the other, there’s an “inevitable…evolution” or “tide” of de-industrialization washing over SoMa.

Sorry, but you can’t have it both ways.

There’s nothing inevitable about de-industrialization. It’s the outcome of policy decisions made by officials who are supposed to be accountable to the public but instead cater to real estate and financial interests.

What’s unsettling the zoning that came out of the Eastern Neighborhood process is not a supervisor’s proposal for a temporary moratorium on PDR displacement, but the Central SoMa Plan, whose upzoning feeds developers’ anticipations of obscene profits.

In fact, the Eastern Neighborhoods rezoning moved both “down” and “up”: it prohibited residential development in some “job districts,” but it also shrank the city’s industrial lands by rezoning a substantial part of the old M-Manufacturing areas for mixed use, a change that forever precluded their survival as light industrial neighborhoods.

The essential point is that light industry cannot compete with high-rent uses—above all, offices and residences. If a community wants PDR, it needs to zone for it and, just as crucial, enforce that zoning.

Given the dire shortage of PDR space in San Francisco—a shortage that has been extensively publicized by SFMade and repeatedly marked in 48 hills as well as in the Chronicle and the San Francisco Business Times—I invite Junius to reveal which owners of PDR-zoned land have vacancies and exactly what rents they are asking.

While we await his response, it’s worth noting that Junius and his colleagues represent property owners who want to convert their PDR property into offices and other high-rent commercial uses, or, in some cases, have done so illegally and now seek official authorization of their illicit action.

For example, an attorney from Reuben, Junius & Rose, David Silverman, was hired by the Rabin family, which own the building at 660 3rd St., to plead its case to the Planning Commission, an effort to whose recent outcome we now turn.

‘Why did you screw up?’

- On September 11 the Planning Commission approved the ex post facto conversion of only half of the building at 660 Third St., illegally converted from PDR into offices 15 years ago

In a perfectly just world, the commission would have just said no to any conversion at all. To allow this change of use is to condone the property owner’s illegal conversion of the building from PDR into offices and the Planning Department’s dereliction in allowing that to happen.

But a big loophole in the Planning Code permits office conversions of landmarked PDR property in the SLI (Service-Light Industrial) district, and 660 Third had been landmarked by the Historic Preservation Commission.

A key factor in the landmarking was Silverman’s testimony at the Historic Preservation Commission that the building was vacant because the owners could not find PDR tenants. But 48 hills investigated and found that the building was actually occupied by office tenants.

Silverman also filed a submittal with the city stating that PDR couldn’t work at 660 Third because the building had no loading capacity. We looked into this claim, too, and discovered that the property has a loading dock and two freight elevators in the rear—features, moreover, that were indicated on the floor plans attached to the staff report.

Consistent with its pro-office, anti-PDR stance, the Planning Department originally recommended that the commission authorize the entire illegal conversion.

Taking the prudent course, the commission voted 5-1, with Moore voting No and Fong absent, to authorize the conversion of the top two of the 80,000 sf building’s four floors, a total of up to 40,000 sf.

With that vote, the commission approved another important but unremarked change from the Planning Department’s original recommendation.

Alerted by Sue Hestor, 48 hills reported in June that the planners have been cheating Muni by not applying the full, legally mandated fees for the impacts of new office development. The May 1 staff report for 660 Third levied a Transit Impact Development Fee of $488,000 on the total office conversion of 80,000 sf. The September 11 staff report got it right, imposing a TIDF of $660,487 for the conversion of only half the building (49,999 sf). This is progress and, we hope, a precedent for future calculations.

During public comment, Hestor assailed the Planning Department for having allowed the illegal conversion of the building by approving permits for “tenant improvements.” “Where is the history?” Hestor asked. “How did it get to this state? How did [you] screw up? Why did nobody catch this?”

In reply, Planning Director Rahaim claimed, rather ambiguously, that “the Department did not review these permits,” and that “there were no permits.” What he meant was that the Planning Commission had never approved the conversion, which is true.

But what Hestor was referring to were the 65 permits issued by the Department of Building Inspection since 1984 for work at the building costing millions of dollars.

As 48 hills reported in May, when the project was last before the planning commission, this work included some substantial alterations—for example, $725,000 to cut new openings in the exterior brick walls, $330,000 to improve the 4th floor, and $304,250 for electrical work.

Two DBI officials, Communications Director Bill Strawn and Deputy Director of Ed Sweeney, told me that their agency runs everything by the Planning Department. “Planning has reviewed [660 Third Street] many times,” said Sweeney.

The routing on the DBI website does not, however, document the Planning Department’s reviews.

Someone’s not telling the truth.

During last Thursday’s hearing on 660 Third, Rahaim made another notable comment: He said that the Planning Department is working on a policy that would allow for one-to-one replacement of PDR space that would be displaced via the rezoning of the Central SoMa Plan. When new Planning Commissioner Dennis Richards asked him to be more specific, Rahaim said: “It’s not established yet whether it’s going to be on-site or off-site replacement.”

Whom, if anyone, in the PDR community is the Planning Department consulting on this project? The last time the city’s planners came up with a proposal for saving PDR was Supervisor Malia Cohen’s PDR-office hybrid bill. The original proposal would have been a disaster, permitting, for example, totally incompatible uses (dormitories, educational and religious institutions, for example) in the non-PDR space of a hybrid project.

Cohen said her office had been working on the proposal for 18 months. It turned out, however, that major PDR proponents and veterans of the Eastern Neighborhoods rezoning—the Council of Community Housing Organizations, the Mission Economic Development Agency, and the Central SoMa Leadership Council—had not been involved.

Thanks to their late inclusion in the planning process, some of the worst aspects of the bill, which is now law, were eliminated, and some of the best aspects of the new legislation, such as making the office-PDR hybrid experiment a three-year pilot project that could only be renewed by the Board of Supervisors, added.

To avoid repeating this unfortunate precedent, the Planning Department would have to immediately convene a task force of PDR advocates who can advise the city on how to ensure the retention of Central SoMa’s light industrial businesses and jobs.

- On September 11 the takeover of the San Francisco Flower Growers Association by Kilroy Realty and likely eviction of the merchants at the Flower Mart was approved by 38% of the SFFGA shareholders — and a dissenting shareholder and merchant sued the SFFGA Board

The plaintiff, David Repetto, runs Repetto Nursery, which has been in existence since 1955, grows flowers, and leases space at the Flower Mart. He also owns eight shares of SFFGA stock. Filed at Superior Court in San Francisco by attorney Robert Kane, Repetto’s lawsuit alleges that the SFFGA Board has neglected its fiduciary duties and thereby damaged the organization’s shareholders.

According to the complaint, the SFFGA was formed as a California non-profit corporation in 1923 by San Francisco residents who grew “flowers, bulbs, plants and the like…to foster and encourage the spirit of cooperation among growers of flowers.”

In 1990 the association’s articles of incorporation were amended and restated to allow the SFFGA “to engage in any lawful business pursuant to general corporation law.” Shareholder eligibility, however, still required individuals to be “a present or former actual bona fide grower or seller of flowers, bulbs, plants, or floral related products” or “an heir of such a person.”

Today the SFFGA has 540 outstanding shares, with ownership limited to 16 shares per person. About 90 shareholders hold between one and 16 shares. The Board has seven directors.

The complaint states that in 2000, the Board developed some of the Flower Mart property as live-work rental lofts. After the development lost a lot of money, the Board, including four of the defendants, Angelo Stagnaro, Ronald Chiappari, Richard Schenone, and Donald Garibaldi, traded “SFFGA’s interest in that project for four out-of-state investment properties.”

Entering into “secret discussions with Kilroy Realty,” a REIT (Real Estate Invetment Trust) about a possible merger with the SFFGA, the “defendant Board members” learned that their prospective partners “wanted to acquire and redevelop the Flower Mart as office space [to] displace the existing tenants who sell flowers.” Kilroy, however, was not interested in acquiring the four out-of-state holdings.

Defendant Board members, without the approval of SFFGA’s shareholders, sold these properties in July of 2014, even though they were earning a return of approximately six (6) percent and as a result of the sale created a taxable event for the shareholders of SFFGA without giving [them] notice or an opportunity to be heard.

The complaint further alleges that, having failed to notify the shareholders of the sale, the Board then “engaged in secret negotiations with Kilroy that culminated in an Agreement and Plan of Merger” dated July 11, 2014. That agreement would end the SFFGA, which “would become a part of Kilroy’s wholly owned entity, KR SFFGA, LLC, a Delaware limited liability company.”

On or about August 20, the Board allegedly notified the shareholders about the agreement with Kilroy and informed them that a meeting to vote on the proposal would take place on September 11.

Accompanying the notice was a single-spaced document prepared by Kilroy that is over 160 pages long. Any requests for additional information had to be received by Kilroy on or before August 29, 2014. The Defendant Board Members encouraged shareholders to provide their proxy to the board so that the Merger would be approved. No one other than the shareholders can attend the meeting[,] making it impossible for shareholders to have advisors present to help them analyze the Merger.

Repetto also contends that “as part of the Merger,” Stagnaro and Chiappari “would be appointed as SFFGA’s exclusive agent in connection with the Merger[,] and that there would be no further involvement by the shareholders, including in the redevelopment plan for the Flower Mart.”

He alleges that other developers are interested in acquiring the Mart for more than Kilroy is offering—developers who, unlike Kilroy, “would continue to maintain and improve the site as a flower mart.” The defendants, however, have refused to deal with them.

Surveying the actions described above, the complaint charges the defendants with having failed to “exercise the care required of directors” by giving the shareholders inadequate notice of the merger and seeking “to monopolize the use of information to support the Merger.” As a result, Repetto “and other similarly situated will [sic] and have allegedly suffered damages based on the loss of their use of the Flower Mart.”

In addition, “the maximum proceeds of any sale will be lost”; the shares of the SFFGA “will not be maximized; and “the development of the Property will done in a way contrary to the interests for which SFFGA was organized and those of the CCSF [City and County of San Francisco].”

Legal cases take a while to wind their way through the courts, and in the meantime, it’s not clear what will happen with the Flower Mart. Any development plans would have to wait until the litigation is settled, one way or the other. And the city planning process would have to move forward.

So the future of the Flower Mart is fuzzy.

Kilroy has not returned my call. Neither has Dan Frattin, the lawyer who is representing Kilroy in its dealings with the city’s Planning Department.

By the way, Frattin’s firm is—you guessed it—Reuben, Junius & Rose.