By Zelda Bronstein

AUGUST 19, 2014 — One of the top San Francisco business stories of early summer revolved around the question: Would the city allow Pinterest, the insanely successful— 53 million monthly active users in the U.S., a $5 billion dollar valuation—four-year-old, online bulletin board company to move into 2 Henry Adams Street, a.k.a. the San Francisco Design Center last June and push out dozens of the designers and dealers who tenanted the four-story, 311,000 square-foot, brick building?

Pinterest had already signed a lease with Bay West Development, which manages the property for its owner, the global, Chicago-based real estate investment firm RREEF; and many of the existing tenants had been placed on month-to-month leases.

Given the tech industry’s sway over San Francisco real estate, Pinterest’s popularity in the mayor’s office—Lee celebrated the company’s 2012 move from Palo Alto to San Francisco—and the immense money behind the Pinterest proposition, this may have seemed like a slam dunk for the social media phenomenon and its hulking, would-be landlord.

It turned out to be anything but. And the story of how tenants organized to fight off the displacement holds important lessons for the future of light-industrial jobs in San Francisco.

The displacement of the Design Center’s current tenants aside, the Pinterest/Bay West deal faced a legal difficulty: 2 Henry Adams is zoned for light industry—in local plannerese, Production, Distribution, and Repair (PDR). Yes, designer showrooms are considered warehouses. But Pinterest, like other tech firms, is officially designated an office use, and offices are generally not allowed in PDR-zoned properties.

There’s a loophole, however: if a PDR-zoned building is designated a historic landmark, the city’s Planning Code allows its owner to rent to offices — ostensibly because the cost of maintaining the historic character of a structure requires the higher, office-level rents.

Hoping to exploit that loophole, Bay West asked the city to landmark 2 Henry Adams. On March 5, the Historic Preservation Commission recommended approval of that request. But the landmark designation had to be finalized by the Board of Supervisors, which would consider it only after it had passed through Board’s Land Use and Economic Development Committee.

Supervisor Malia Cohen, who sits on that committee with Supervisors Scott Wiener and Jane Kim, drafted a resolution to landmark 2 Henry Adams, which lies in her district.

The resolution never got out of the committee.

It ran into three formidable obstacles: a mobilized design community; the mounting public resistance to tech’s hyper-gentrification of San Francisco; and Cohen’s re-election ambitions.

At the Land Use Committee’s June 16 and July 7 hearings on Cohen’s proposal, some of the tenants at 2 Henry Adams voiced their support for Pinterest’s move. More of them, however, opposed it.

But the decisive expression of community opposition to the Pinterest lease occurred on June 27, when Cohen met with about 125 people at one of the Design Center shops, Garden Court Antiques.

According to Jim Gallagher, who manages Garden Court Antiques, and who organized the meeting, Cohen asked how many present were tenants. About half raised their hands. “Who are the rest?” she wondered. The others explained that they represented the upholsterers, refinishers, movers, and other “back streets businesses” that provide crucial support to the designers and dealers at the Design Center.

At that moment, Gallagher says, Cohen realized that she was dealing with something much bigger than the landmarking of 2 Henry Adams.

That revelation gained force at the July 7 hearing.

By then more than 2,000 people had signed a “Save the SF Design Center” MoveOn petition. Most listed Bay Area residences, but Chicago, San Antonio, Kamuela, Hawaii, and Vancouver, Canada, among other distant locales, also appeared after signatories’ names.

Addressing the committee, designer Warren Sheets, who said he annually does “$10 million worth of business with these showrooms” and is “in there daily,” asked, “Why bust up a large community that has been here for 30 years?”

Besides testifying to the value of the invaluable and irreplaceable propinquity afforded by the Design Center location, opponents of landmarking the building decried the tech industry’s displacement of the city’s light industry.

John McEvoy, whose art gallery has been at 2 Henry Adams for 24 years, said he uses Pinterest and Instagram in his work. “But this,” said McEvoy,

is not about Pinterest. It doesn’t matter where Pinterest is located. [It] could be in India. The problem is putting office tenants in PDR space….It’s not just this one building.

McEvoy asked the committee view the situation “holistically” and “put together a citywide plan to deal with the shrinking PDR space in the city.”

The most rhetorically resonant comment came from former Mayor Art Agnos. Calling the loophole in the Planning Code that allows office in landmarked PDR buildings “a commercial version of the Ellis Act,” Agnos urged the Land Use Committee to “kill this bill” and “close that loophole.”

According to the media, the committee did kill the bill. “Pinterest headquarters deal in Design District tabled,” read the headline over Chronicle reporter J.K. Dineen’s July 8 story. “As the sponsor of the property’s landmark legislation, Cohen,” wrote Dineen, “Cohen is the only supervisor who can revive it. She said she has no intention of doing so.” San Francisco Magazine, “Socketsite,” “SFCurbed,” and the Bay Guardian all filed similar reports.

In fact, the proposal to landmark 2 Henry Adams was not killed; parliamentarily speaking, it was only anesthetized.

Which is to say that instead of tabling the item, at Cohen’s behest the committee continued the bill to the call of the chair, as the minutes from the July 7 meeting indicate:

140307

[Planning Code – Landmark Designation of 2 Henry Adams Street (aka Dunham, Carrigan & Hayden Building)] Sponsor: Cohen Ordinance designating 2 Henry Adams Street (aka Dunham, Carrigan & Hayden Building), Assessor’s Block No. 3910, Lot No. 001, as a Landmark under Planning Code, Article 10; making environmental findings, and adopting findings pursuant to the General Plan, and the eight priority policies of Planning Code, Section 101.1.

….

CONTINUED TO CALL OF THE CHAIR by the following vote:

Ayes: 3 – Wiener, Kim, Cohen

I asked the Board of Supervisors’ Clerk’s Office to explain the difference between tabling and continuing. Arthur Khoo emailed this reply:

Tabling – items that are no longer active and filed away

Continuing – items that are still open but dormant

Continued to the Call of the Chair – Items to be called up in the future at the Chair’s discretion

The source of confusion in the media and, to this day, in Cohen’s office, was apparently her initial motion “to table [the item] at the call of the chair.” No such motion exists. Hence, Wiener asked her: “Table or continue to the call of the chair?” “Continue,” Cohen replied. And that’s what the committee did.

Technically speaking, this means that only Wiener can bring back the landmarking proposal. It’s unlikely that he will do so: The supervisors customarily defer each to other on items that concern their respective districts. Her parliamentary miscue notwithstanding, Cohen surely means it when she says that she doesn’t intend to revive the landmarking of the Design Center—at least not before the November election—for such a move would undermine her presentation of herself as a protector of PDR.

In cultivating that image, she often alludes to the legislation she sponsored earlier this year that’s intended to provide new PDR space on 16 parcels in the Mission by subsidizing that space with new office development.

As 48 hills reported, Cohen’s original bill left much to be desired. In response to appeals from the Council for Community Housing Organizations, the Mission Economic Development Association, and the SoMa Leadership Council, Cohen extensively amended her original proposal: She added a three-year sunset clause; deleted child care, residences, and religious and educational institutions from the list of permitted uses in the new non-PDR spaces; and required a project owner annually to report current rents or lease terms for the PDR spaces to the Planning Department.

But she refused to make a crucial change sought by both these longtime PDR advocates and Supervisor David Campos: require at least 50 percent of the spaces in the so-called Small Enterprise Workspace projects to be for PDR. In other words, under the new law, an entire SEW development can be offices for tech start-ups.

Cohen’s legislative initiatives around 2 Henry Adams display commensurate shortcomings. I’m thinking partly of the 18-month interim controls on landmarking PDR buildings that she proposed at the Land Use Committee’s July 7 meeting. Approved by the Board of Supervisors on July 25, those controls require:

- an applicant to provide the Planning Department with a complete economic impact analysis of the proposed use, prepared by an independent licensed professional; and, if necessary a tenant relocation plan

- the Planning Commission to consider the availability of space for PDR uses in the surrounding neighborhood, the compatibility of the proposed commercial office use with PDR uses, and the land use and planning effects of displacement of any existing tenants

All this is regrettably vague. Exactly what factors are to go into the economic impact analysis, and how are they to be evaluated? Ditto for the compatibility issue. Will proximity to clients and other PDR businesses be considered in relocation plans? What kind of voice will existing tenants have in the decision?

Even more problematic are the additional interim controls that Cohen has proposed in a bill filed with the Board of Supervisors’ Clerk (File No. 140876) that will shortly come before the Land Use Committee.

The draft legislation shares a significant weakness with existing law: it doesn’t require an application to demonstrate the financial need to convert a PDR property into offices. Thus, the staff report to the Historical Preservation Commission contained no information about the cost of restoring and maintaining the historic character of 2 Henry Adams or how that measured up against the revenues yielded by current, PDR rents.

Instead of requiring an applicant to provide such data, Cohen’s bill offers a mechanistic formula:

no office use in a 1-story building; 1 story of office use in a 2-4 story building; 2 stories of office use in a 5-7 story building; and 3 stories of office use in a building of 8 or more stories

Somehow Cohen missed a major lesson of the 2 Henry Adams episode: not every PDR building needs office rents to restore and maintain the building’s historic qualities.

Here, for example, are the financials for the Design Center, as Gallagher laid them out in a Bay Guardian op-ed:

According to the building owners, there are approximately 262,000 square feet of rentable space in the building. The Common Area Maintenance or CAM fees that tenants of the building pay beyond their monthly rent is $1.25 per square foot per month. This would mean that the owners of the Showplace building are currently bringing in nearly $3,500,000 just in Common Area Maintenance fees annually. In what universe is this not enough money to maintain a building that was fully retrofitted 15 years ago and is only five [sic] stories high?

The idea that this building needs to granted Landmark status from the city in order to create enough revenue to maintain the building just does not pass the smell test! This is a case of simple greed on the part of a Chicago based investment company.

Both the proposed and enacted interim controls have another problem: they apply only to PDR buildings in Cohen’s district. But the loss of PDR space is not peculiar to District 10; as speakers repeatedly told the Land Use committee, it’s an issue for the entire city. The businesses that support the shops in the Design Center are scattered throughout San Francisco.

The same goes for Supervisor Jane Kim. A little-noticed provision of the deal Kim struck with Ed Lee over her Housing Balance ballot measure calls for “interim planning controls in the Central SoMa [i.e., in Kim’s District 6] to prevent displacement in advance of the approval of the Central SoMa Plan.” The details are being worked out in the City Attorney’s office.

Given the Central SoMa Plan’s open admission that its approval will wipe out nearly 2,000 PDR jobs, any curbs on that destruction would be welcome. But as with Cohen’s bill, the question is: will the details have any teeth? Even if they do, to be truly effective, PDR policy needs to be formulated on a citywide basis, not supervisorial district by district. That will be a formidable project.

For starters, the laws governing the conversion of PDR space into office vary according to each zoning district. Even more daunting, the creation of new office space of less than 25,000 sf does not require Prop. M authorization, meaning that it can be done without a public hearing or formal documentation.

That’s how one of the two properties that currently houses Pinterest’s headquarters—527 7th Street—was converted from PDR to into offices. The building is in a UMU (Urban Mixed Use) zone, where conversion is allowed, but not on the ground floor. The owner of the property got around that restriction by having the property listed on the California Register of Historical Resources and then going to the Historical Preservation Commission with a Historic Building Maintenance Plan (no financial data supplied).

The Planning Department found that the plan would support the preservation of the building, and on April 3, 2013, the commission approved that finding. The application to convert the PDR use to offices then went to the city’s Zoning Administrator. Because 572 7th St. comprises “only” 14,973 square feet, the Zoning Administrator legally could and did approve the change over the counter. From the perspective of Salesforce or Google, 14,973 square feet looks negligible. As viewed by most PDR businesses, it’s huge.

Since no formal documentation is required when less than 25,000 sf of new offices is involved, is there any way of knowing how much PDR space has been lost to offices in this fashion?

Even if the 25,000-sf loophole were closed—a change that would take a vote of the people—along with the loophole that almost enabled Pinterest’s move into the Design Center—a change the supes could make themselves, San Francisco’s industrial lands would still face another threat: the Planning Department’s lackadaisical enforcement of the city’s zoning laws and its anti-PDR, pro-office (especially tech office) bias. Eliminating that danger would require a basic re-orientation of the department’s culture and ideology.

Absent the requisite legal and bureaucratic overhauls, Production, Distribution and Repair space is going to keep shrinking. According to a report that planner Steve Wertheim delivered to the Planning Commission on June 12, San Francisco now has only 1,274 acres, or 5.6% percent of the city’s land, zoned for PDR. And a sizable portion of that land may not currently be devoted to PDR uses.

In explaining her decision not to pursue the landmarking of the Design Center, Cohen cites her concern about a million square feet in fourteen buildings on 16 parcels in currently zoned PDR-1 D [Design] and PDR-1 G [General] areas (all in District 10) that are eligible for landmark status and thus vulnerable to office conversion.

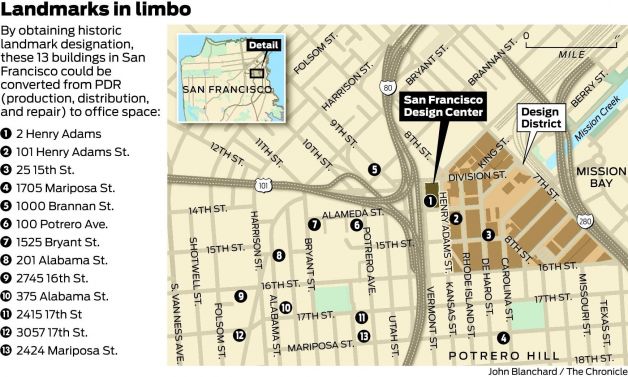

The lead story in the June 20 Chronicle included a map showing the location of thirteen of those buildings that, it said, was based on a list that Cohen had asked planning staff to compile.

48 hills obtained a copy of the list and the accompanying report from the Planning Department. We discovered that by the planners’ own reckoning, only 75% of that million square feet of PDR-zoned space is actually being used for light industry. Fifteen percent has already gone to offices.

The loss is parceled out among five addresses on the list: 1000 Brannan (24,998 sf), 2 Henry Adams, (10,401 sf), 100 Potrero (70,070 sf), 375 Alabama (29,668 sf), and 2424 Mariposa (3,607 sf).

Here’s the breakdown:

Land Use Gross Total Sq. Feet % Sq. Ft.

PDR 724,230 75%

Office 139,744 15%

Vacant/Storage 74,691 8%

Retail/Entertainment 11,273 Cultural/Institutional/Educational 10,000 1%

Grand Total 960,208 100%

And the planners’ report, dated March 14, 2014, included a caveat: “Please note that these are estimates based on the best available data, and that uses within buildings may change.” You can bet that the change is in the direction of less PDR.

Reversing that change is going to take the same thing that defeated the landmarking of 2 Henry Adams: the mobilization of the PDR businesses and workers whose livelihoods are at stake.

In some ways the Design Center tenants were lucky: Cohen is up for re-election, and the dearth of PDR space has already been well publicized by SFMade, the most prominent advocate for manufacturing in the city.

But if the tenants hadn’t banded together and vigorously made their case to Cohen and the public, chances are that Pinterest would be preparing to move into the Design Center (instead, it’s leased space at 888 Brannan, the same building that houses AirbnB).

The importance of a vocal and organized community be seen by contrasting the situations at 2 Henry Adams and the 16 parcels in the Mission affected by Cohen’s PDR/office development legislation. Unlike the Design Center, with its established group of businesses, workers, and supporters, and a large, contiguous base of operations, the Mission properties were scattered throughout the neighborhood. The demands for stronger zoning protections than what Cohen was proposing came from non-profits (CCHO, MEDA) and activists who’ve long advocated PDR throughout San Francisco (Sue Hestor, Jim Meko), not from the tenants at the Mission properties themselves.

Perhaps those tenants would have come forward if, as at the Design Center, the office—make that tech office—takeover of their spaces had been an impending reality, not an abstract possibility.

And perhaps they will if they see that resistance to the creeping, Borg-like land grab by tech offices is not futile, that PDR space can be saved. That’s the lesson of 2 Henry Adams.