This is a critical time for our city. There are a lot of important issues at stake that matter to all of us. Income inequality. Homelessness. Drugs. Auto burglaries. Educational reform. The list goes on and they are all important.

From my perspective as a former mayor, though, the biggest issue that is to be decided in San Francisco is this question:

“How big does SF want to be, and who do we want to build for and where?”

The answer will determine where most people like us or their families will be able live here in the future.

You see, the mistakes we build today cannot easily be fixed by future generations.

It took us 35 years to eliminate the monstrosity of the Embarcadero Freeway.

It took 30 years to eliminate the ugly Central Freeway as it cut through the heart of Hayes Valley.

More recently, how many years will it take to fix the Millennium Tower as it leans and sinks into the ground because of a faulty foundation approved by our Planning Department?

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

How are the new homeowners in the Hunters Point Shipyard going to be assured they bought safe homes when we now learn toxic cleanup studies were falsified by corrupt contractors?

No matter what you think of it, how many more Salesforce buildings should we build to meet whose demand?

All too often these questions have been decided exclusively in favor of developer profits.

SF citizens must take back control of the planning process in City Hall that has been dominated by the big developers from all over the country.

In my opinion, the Planning Dept has become a permit processing department for the developers who have but one incentive: huge profit, how much money can they make for themselves and their investors.

This has created a new Gold Rush in SF.

In 1850 SF witnessed its first gold rush.

That one was about precious metal to be found in the ground. And that gold rush was open to everyone who wanted the opportunity and most were not rich.

They came from everywhere for the opportunity to achieve success for themselves and their families.

Today’s gold rush is also about something precious connected with land again — but not what’s in it. It’s about what you can build on top of it — high rise luxury housing and office buildings.

And today’s gold rush is only available to the wealthy that come from everywhere.

SF is surrounded by water on three sides with Daly City on the south.

Thus in a mature city like ours, the only space to build is upwards.

So the question is this:

How big do we want to be – and for whom?

Right now, we are 785,000 people living here.

Shovel ready projects — ready to go and approved — will take us to 1.3 million residents without anything else being built. That doesn’t count the million or so who commute in every day to work.

Big enough?

No?

Ok. Just how big do we want to build this city to be in population?

Two million? Two and a half million? Three million? Four million?

And for whom do we want to build?

Where?

That decision begins with our elected leadership in general and the mayor in particular.

That decision should be followed by an immediate citywide discussion neighborhood by neighborhood, led by a mayor who understands SF values of inclusion, diversity, affordability, and quality.

This is a city that has always promised newcomers the opportunity to come here, find a place to live, find a job, be who they wanted to be, with whomever they wanted to be it with, as long as it did not interfere with someone else’s opportunity to the same thing.

Not so much anymore. That promise is severely diminished today because of the cost of housing.

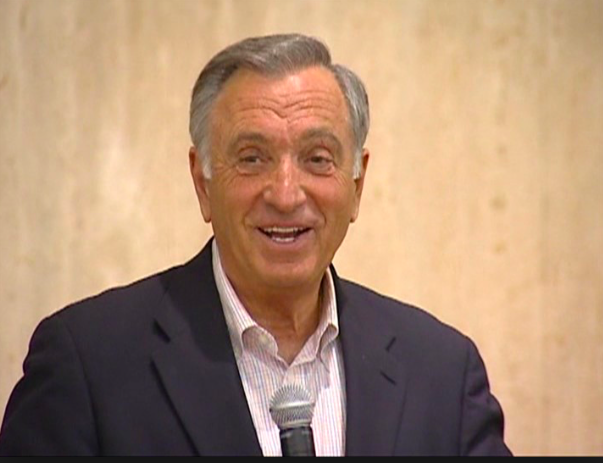

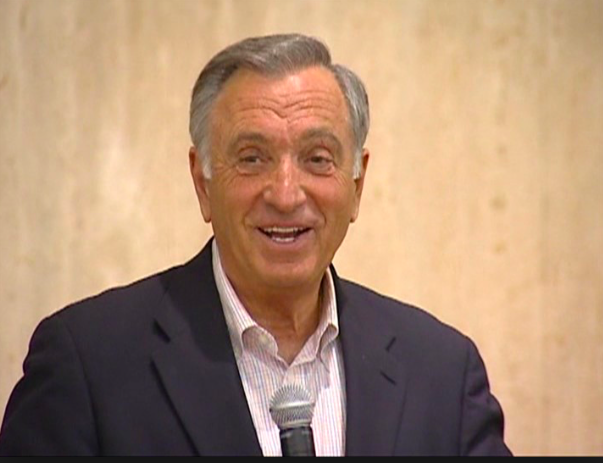

My story is the story of the SF Promise.

I was born to Greek immigrants one year after they arrived in this country.

Like most immigrants, my parents spoke Greek at home to me so I didn’t speak English when I went to school.

My father shined shoes, and I shined shoes next to him until he died of cancer when I was 15.

I ran the shoeshine store until my mother learned to do it so I could finish high school and be the first in my family to go to college.

But in my hometown in Massachusetts, I couldn’t date certain girls.

Their fathers said I was too. “Mediterranean.”

I wasn’t invited to join certain social groups

In short, I don’t think I could have been elected mayor of my hometown.

So I left, for as far as I could go, from one coast to the other, and came to San Francisco on a Greyhound bus not knowing anybody west of the Mississippi river.

Got off the bus on my birthday in September 1966 and started looking for a place to stay and a job.

In a week, I found both.

Nobody asked me who my father was, where he went to college or what clubs he belonged to.

They asked me who I was and what I did.

Ten years after I got off that bus in September of 1966. I was elected to the California State Assembly.

Twenty years after I got off that bus, I was elected mayor of this great city.

I still marvel that a city like San Francisco gave this shoeshine boy, son of immigrants, the opportunity it did 52 years ago.

Friends — I could not do that today!

It would be too expensive for me now.

Like many working middle class folks looking to come here today. I would be looking at Oakland, San Jose, or Sacramento instead because of affordability.

We are all aware of the physical infrastructure impacts that prevail in our city.

But in my opinion, the situation for housing middle class workers is so critical that it also threatens the socialinfrastructureof our city.

How do you maintain excellence in our schools if you cannot attract good teachers to come here because they can’t afford to buy a home or rent at a starting salary of $57,000 a year?

We have a great medical system here, but who will support the doctors in our hospitals and clinics if the nurses, nurses’ aides, X-ray technicians and the other essential personnel can’t live here but have to commute from Tracy?

Too many of our public safety-first responders live outside the city for the same reason.

The list goes on – artists, librarians, restaurant workers,department store workers — you get the idea about social infrastructure.

We are told there are 37,899 subsidized units in SF.

Only 3,382 of those — about 9 percent — are for qualified moderate or middle-class applicants. A recent housing lottery for 28 new units to replace the old public housing next to Candlestick drew 4,000 applicants.

Some capitalist cynics might say so what? That is the way the market works and those that can afford high prices will come and those who can’t afford it will leave.

Progressives say not so fast.

We can require that the market in San Francisco to do better for all of us, not just the rich.

For the most part city government was passive in responding to the crisis of affordable housing in any significant way.

In the absence of leadership from City Hall. some of us have used the Citizen Initiative to require housing for the poor and middle class.

In 2014, citizen activists qualified a first of a kind, revolutionary measure entitled Prop B to require a citywide vote for any development seeking to raise heights on the 7.5 miles of city owned port property.

The first developer to seek a citywide vote at Pier 70 on the southern waterfront was Forest City.

And look what happened.

In order to gain the support of citywide voters, the Pier 70 plan offered 2,000 units of housing with 33 percent affordable housing for people with incomes up to $140,000 for a family of 4. One third of the project was for open space and parks paid for and maintained by the developer but given to the city. New low rent space on site for 90 artists. Strong remedies for sea level rise. All paid for by the developer who always said they will make money!

The people of SF loved it, and showed their appreciation at the polls with a landslide favorable vote of 72 % to approve the Pier 70 project in November of 2015.

Right behind that vote came the SF Giants Mission Rock proposal for another 2,000 units on their current parking lot.

The Giants project took note of Pier 70’s success and called for 40% affordable housing for families up to $150,000 a year, as well as all the same community benefits as the recently approved Pier 70 project.

And get this: The Mission Rock project includes 20 low rent units for emancipated foster kids — not in some crummy SRO hotel in the Tenderloin, but on the waterfront where the rich people live!

Again the people of SF voted in favor of the Giants housing development with 73%. And the Giants also say THEY are going to make money.

Perfect. The developer makes money. SF gets affordable housing for the poor and middle class as well as community benefits that mean something and make a difference right away.

All this was done — 33% affordable housing at Pier 70 and 40% affordable housing at Mission Rock — when official city policy was still 12% on site and 15% off site in a law passed 18 years ago by then-Supervisor Mark Leno.

Why?

When developers go to city hall to get attention, they offer a $500 campaign contribution or they donate hundreds of thousands in donations to an independent expenditure committee to support a candidate for city office. or they give millions to the mayor’s favorite project like the America’s Cup or the Super bowl host committee.

When developers come to the neighborhoods to get attention for a vote in accordance with Prop B to support their waterfront project, a campaign contribution means nothing.

What means something to a neighborhood is affordable housing, parks and open space, transit, child care, the arts, schools, local hire jobs, neighborhood serving shops so that there is a place for all of us in this great city of opportunity.

That is the San Francisco promise.

So these two projects. Forest City Pier 70 and the Giants Mission Rock have set a new standard for affordability and community benefits in this city because of a citizen initiative — not City Hall.

Sure, the capitalist critics said, that is easy to do on public land. but the private land deals don’t pencil out like that.

Not so fast. Just three years ago, Forest City, the same developer who broke new ground at Pier 70 on the waterfront, negotiated another totally private development deal with the Hearst Corporation known as the 5 M project at the Chronicle building on Mission Street.

That project will pencil out at 40% affordable housing in a private deal between two private companies enhanced by the advocacy of Supervisor Jane Kim.

We would not be talking about a housing crisis if we had continued to build on Mark Leno’s original legislation or Jane Kim’s advocacy to require 40% affordable housing.

So it is possible to get what we want if we have leadership in City Hall that recognizes and responds to the needs of our neighborhoods.

Our mayor must remember San Francisco neighborhoods by putting them in Room 200 where she sits.

I know that room.

You know who is always in that room?

It is the developer, the department head, the lobbyist, the business leader, the contributor, the planning director, the commissioner.

You know who is not in the room?

You.

If you want to be heard, you leave work, go to the Board of Supervisors, sign up to speak at a committee hearing, wait a couple of hours to speak for two or three minutes and then get “gonged” into silence if you take longer.

That is not enough by itself. We must have a mayor who remembers you and what your neighborhood needs for our city to remain affordable and livable for all of us who do not have big checkbooks.

The best policy is for the mayor to appoint strong pro neighborhood commissioners to the Planning Commission, the Board of Permit Appeals, and other important bodies from a list compiled by neighbors just as Mayors Moscone and Agnos did in their time.

The mayor must insist that City Hall policy on inclusionary housing match what the neighborhoods have done on the waterfront — 40%.

The mayor must be strong enough to tell developers that if they don’t think they can make money with our newest standards, then step aside. Don’t do the project if you think you will lose money.

We will take the next developer in line and see what they can provide within our policy.

And if we run through the line of applicants and there is no one who can meet our community affordability standards and still make money the way Forest City and the Giants did, then we bank the land and wait for a developer who can meet our terms as we define them.

In this modern real estate gold rush we won’t have to wait long.

If the mayor fails to address election our neighborhoods’ interests. we will return to the Citizen Initiative to protect the San Francisco promise.

We can seek a requirement for a Prop B like citywide vote on projects over a certain size.as we did on the waterfront.

We can seek a requirement to decentralize the Planning Department to support neighborhood planning committees like those in New York city and Washington DC.

No matter who is in charge of City Hall, the ultimate power resides with us, the people of San Francisco.

No one can take it. But we can lose it by not staying informed, organized, and engaged every step of the way.

This piece is adapted from a talk Agnos gave to the District 11 Democratic Club June 1.