So how are we supposed to think about 2020?

Was it the year that a few news media outlets (including even Bloomberg) finally figured out that trickle-down economics doesn’t work?

Was it the year, as Paul Krugman argues, that Reaganism died, that the American public, after 40 years of lies, got the message that the public sector can be (and often is) the only source of help in a crisis?

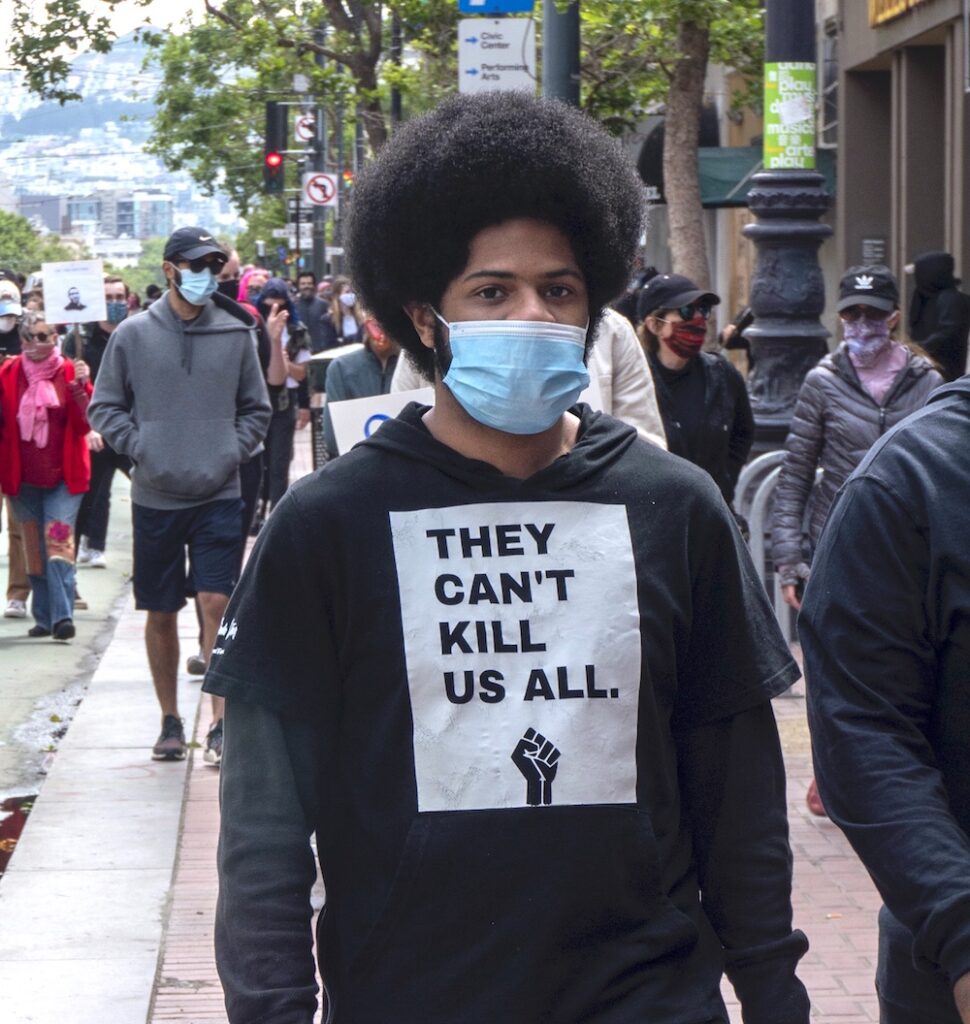

Was it the year that massive public protests forced changes to the way the country thinks about race and policing?

Was it the year that taught us that going “back to normal” is not going to work?

Or are we all just going to get the vaccine, mourn our losses, and allow the Biden-Harris Administration to act like “moderates” and preside over four years of late-stage capitalism that lets the very rich get much richer and the rest of society to approach collapse?

When my kids look back on 2020, a year that disrupted their educations and jobs, that saw the personal relationships young people take for granted shattered, that upended the global economy, will they think it was a turning point?

Or was it a chance for the people who have manipulated the economy for their own interests to find new ways to make greed the determining factor in society (while the government at best looks the other way)?

I am always an optimist. It keeps me alive. But right now, I am not all that optimistic.

Let’s start with the good news. On January 20, Donald Trump will be out of office. There are vaccines on the way, and by April or May, it’s likely that most of us will get one. So by summer 2021, people will be able to do what people do in the summer – travel, see friends and family, vacation … and if all is well, go out to eat, go to bars, go to dance clubs, and live the way we lived before COVID.

That’s if there are many restaurants, bars, and clubs left. It’s entirely possible that the nation’s nightlife, arts, and entertainment world will be so deeply damaged that it can’t easily recover.

The federal “stimulus” money is radically inadequate. The term is all wrong; this isn’t a “stimulus,” it’s disaster relief.

By fall, 2021, schools will be open again. But students, particularly at the K-5 level, will have lost a lot of time, and it will require a lot of money – public money – to help them catch up.

Colleges will be open. Students will come back to campus. I know from personal experience that teaching on Zoom doesn’t work as well as teaching in a classroom. The students know that too. College is an experience that goes beyond classes; if schools can survive the next semester, they will be back in business in the fall.

Some economists, like Paul Krugman at the NYTimes, say that if unemployment payments and stimulus money keeps people alive through the rest of the spring, the economy will rebound in the summer and fall as all of the “pent-up consumer demand” starts getting spent. Millions of people are going to want to travel, to vacation, to shop in person, to eat in restaurants. But that assumes that people who have been out of work for months still have any money to spend.

I don’t know how seriously the new administration will take the climate crisis – but at least Biden admits it’s a real problem. Which is pretty hard to ignore. But solving it will require a massive public-sector effort, and Biden’s been dismissing the idea of a Green New Deal.

In a fascinating SF Chron article, reporter J.K. Dineen talks about what’s going to happen to the local housing market. Here’s the first paragraph:

Market-rate housing development in San Francisco will grind to a halt in 2021 as a crop of new buildings opens up and tumbling rents and condo prices combine to shut off the flow of capital into the city’s real estate markets, builders and analysts say.

That’s one of the most important sentences the Chron has run on the housing market in a long time.

Dineen, who is a good reporter and has extensive contacts in the real-estate industry, is telling us how the housing market really works: It’s not about zoning, or regulations, or Nimbys. It’s about investment capital.

And when prices for market-rate housing start to drop, the flow of investment capital stops.

In other words: The entire Yimby narrative is out of touch with economic reality. You can’t bring down housing prices by eliminating zoning restrictions and allowing more market-rate housing – because as soon as prices start to drop, investors stop putting money into new housing.

Tumbling rents, which we all want, mean an end to new housing construction. The housing market in San Francisco is dependent far more on the needs of international speculative capital than on zoning decisions and neighborhood appeals.

As one of Dineen’s sources notes:

While L37 Partners has two apartment projects totaling 500 units that have yet to start construction in the South of Market neighborhood, Tao doesn’t expect investment funds to be available before 2022.

“I’m a conduit for large capital investment and can only deploy capital to build housing when the math is right,” he said. “Right now the math isn’t right.”

So the good news is that housing costs are coming down. The bad news is that the likes of state Sen. Scott Wiener still seem to believe that allowing more density – by itself – will bring down prices.

The reason housing prices are coming down in SF is not because of the elimination of “red tape” or looser zoning rules. Prices are coming down because demand is weak. COVID convinced lots of people who had enough money to move out of congregate condo buildings and into single-family units in the suburbs (where housing prices are soaring – not because of zoning but because that’s where rich people want to live now that they can work from home anywhere and they don’t want to ride in crowded elevators).

The Yimbys always seem to ignore the demand side of the equation. Maybe now that we have a clear case study the politics of housing will change.

I don’t know what happens to the office culture in the next few years. Maybe a lot of downtown office buildings never fill up again; maybe they can be turned into housing.

I don’t buy the idea that cities are done, that COVID and Zoom have taken away all the reasons that people live in places like San Francisco. Cities are eternal. In the past 2,000 years, probably 250 different entities have governed what we now call Italy – but Rome has survived it all. Paris, London, Bejing … New York, San Francisco – long after the United Kingdom and the European Union and the People’s Republic of China and the United States of America are gone, great cities will remain.

If housing prices and office rents crash in San Francisco (and a 20 percent drop in rents isn’t relevant – a $3,000 a month apartment that now costs $2,400 still isn’t affordable) maybe the city will once again become a mecca for artists and writers and musicians and people with crazy wild ideas that don’t involve an IPO.

I can live with that.

But here’s the bad news: The COVID era is creating a new debt crisis, on the level of student debt – and nobody at any level or government is dealing with it.

We have a moratorium on evictions all over the country (although some are starting to expire). Landlords have been told that they can’t throw a tenant out on the streets because missed rent payments while so many have been out of work.

But that back rent doesn’t just go away. It becomes consumer debt, like student loans and credit-card debt. And for a lot of low-income and working-class people – and even a lot of professionals – that’s a debt they are never going to be able to pay without putting themselves into poverty.

And so much for the “pent-up consumer demand.”

I’m glad Bernie Sanders is pushing for $2,000 stimulus checks. But seriously – how far will that go to pay off eight months of back rent?

And what about the small landlords who haven’t been able to collect rent, and might be avoiding mortgage foreclosure but can’t forever?

This is an issue with profound implications, on the level of the past foreclosure crisis that pretty much broke the economy in 2008.

The US economy doesn’t have to collapse again in 2021. It’s actually pretty easy to address this. What we need to do is stop relying on individual initiative and start acting like a civil society.

And that will involve income and wealth redistribution.

The money that US billionaires have made since the crisis started is close to $1 trillion. There are about 122 million households in the US.

Do the math: An excess profits tax just on the wealth that the richest 600 people in the country made since March could give every US household about $8,000. That’s a start.

But Joe Biden isn’t talking about that. Kamala Harris isn’t talking about that. Nancy Pelosi isn’t talking about that.

When the US economy fell victim to stagflation – huge amounts of unemployment and inflation at the same time – in the late 1970s, the Milton Friedman types who wanted an end to the Keynsian bargain of taxes, unions, and government action in the economy had their own plans in place. They had been working on what we now call trickle-down economics and neo-liberalism for decades.

And when Ronald Reagan was elected president, he called on them to put their plans into place.

We now know that the result was a disaster. The Reagan approach didn’t work. It made things much worse for most people, and aided only the rich, and created vast economic inequality.

There are plenty of people (and Sen. Sanders is only one of them) who have well-formed alternative economic proposals that could be put in place in the wake of the pandemic to radically shift the economy away from the failed policies of the past 40 years.

But they are not in the Biden cabinet. They are not his economic advisors. They will not play the role in his administration that Milton Friedman and his disciples played in the Reagan White House.

No: What we have is mostly a team from the Obama years, and in some cases from the Clinton years.

We have people who have embraced neo-liberalism. We have nobody who wants to make economic equality and racial equity a defining issue.

So we are going to face a massive crisis, with nothing but solutions that we know are not going to work.

Happy new year.