Early on in the pandemic, San Francisco was celebrated nationally for its swift and organized response to COVID. In particular, its Shelter in Place hotel program, which temporarily housed homeless people in subsidized hotels, was seen as a national model for responsible pandemic planning. A recent medical study attributed San Francisco’s early policy decision to house homeless individuals who may have come in contact with coronavirus in hotel rooms with preventing the spread of the virus and potentially freeing up thousands of hospital beds city-wide.

But many homeless advocates have regarded the city’s program as halting and inconsistent, requiring community-funded efforts to fill in the gaps. Over the past 12 months, homeless allies have pressured the city to include more people in the SIP program, District Supervisors rented their own hotel rooms ahead of official approval, and groups like Hotels Not Hospitals continue to pay for hotel rooms for people who don’t qualify for city-sponsored rooms.

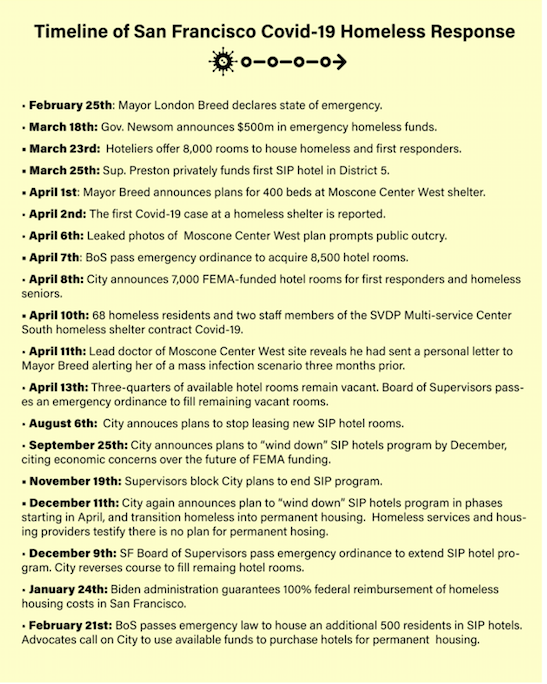

On February 25, 2020, San Francisco Mayor London Breed declared a state of emergency due to the global outbreak of coronavirus. By the beginning of March, cases in the Bay Area began to multiply, and on March 5, San Francisco’s first case of community-transmission was reported. A week later, Governor Gavin Newsom announced the first of what would be many directives to Shelter-in-Place, ordering California residents to shelter inside their homes. The dilemma was obvious: thousands of homeless Californians have no homes in which to shelter. This included the approximately 40,000 seniors living on the streets of California. Local jurisdictions were instantly forced to confront the unique threat posed by the overlapping public health crises of homelessness and COVID.

In San Francisco, as in other cities such as Los Angeles, the process has been convoluted and marked by periods of inaction. At first, the city opted for high-risks choices like congregate shelters, even when hotel rooms were available, then began the hotel program only after pressure from advocates and the Board of Supervisors. The city made attempts throughout the year to downsize or close the program, but instead expanded it following community pressure.

According to the city’s most recent data, 1,929 people are currently occupying SIP hotel rooms. Those hotel rooms have temporarily housed 9,564 individuals since they were first made available. But that number is still just a fraction of the total number of people that could have been housed had the program been utilized consistently throughout the past 12 months, and to its full capacity.

Inaction on the part of the city lead to District 5 Supervisor Dean Preston renting out the first SIP hotel rooms at the Oasis Hotel paid for with private funds, as well as to the formation of Hotels Not Hospitals, a group that “exists to book hotel rooms and provide safe, temporary housing for our homeless neighbors—and in doing so, lay bare the city’s poor excuse for its inaction.” The group of volunteers works independently of the city or non-profits to raise funds to put homeless people into hotel rooms who would otherwise not qualify for the city’s official SIP program.

The effort, say members, began very early on in the pandemic but took several months to get off the ground. Initially focused on advocating for the city to utilize all available money to fully fund the program, the group also temporarily organized to help replace tents seized by DPW and SFPD during street sweeps. Hotels Not Hospitals volunteers say they then spent a number of months approaching the vast network of existing homeless charities, non-profits and service and housing providers. But none said that they capacity to help with the goals of autonomously renting additional SIP hotel rooms for people outside of the city’s requirements for FEMA reimbursement.

Thus, the biggest challenge Hotels Not Hospitals has faced so far is to successfully create their own framework for the organization’s members that reduces individual liability as well as other financial barriers. As it turns out, there are a number of barriers to renting hotel, motels or SRO rooms on behalf of homeless people. Many SROs now require credit scores and rental histories to rent for longer than a week. Many also have rules against co-signing on behalf of a guest—making renting a hotel room on a long-term basis very difficult for someone who wants to help.

Eventually, they created an LLC called Solidarity Works through which hotel rooms have been rented. The group say they that were kicked into high gear and began the program in earnest after Mayor Breed indicated she would ignore the Board of Supervisors resolution to house 8,000 people. “Living on the street during the pandemic is life and death,” says Judy Jiajing Wang, a volunteer since summer. There are now nine individuals who have been continuously sheltered in hotel rooms through Hotels Not Hospitals since they began in June.

John, 42, has spent the past four months in a Hotels Not Hospitals room in the Haight by Golden Gate Park. Originally from Los Angeles, he has experienced poverty and intermittent homelessness his whole life. But it wasn’t until the early 2000s, when John contracted West Nile Virus and developed severe and prolonged neurological symptoms that he couldn’t afford to treat, that he became chronically homeless. Being homeless lead him to start using drugs, “mostly just to try to sleep.”

Having a place to stay has “turned my life around,” says John. “Having housing helps your sanity. When you’re sleeping outside, you never really sleep… it’s like being in a war zone, you lose your sense of reality.” Prior to finding a free hotel room through Hotels Not Hospitals, John would sleep wherever he felt safe, avoiding streets with a lot of traffic and never staying in the same place twice. He was constantly looking for a place where he would be out of the way, in order to avoid sweeps, as well as angry neighbors and their video cameras.

Since finding the room, John has had the time and resources to find a job but is still trying to make enough money to buy a car. “When you’re homeless, you have to take every day one day at time. When you have housing, you can plan for the future.”

Hotels Not Hospitals say their ultimate goal is to set a precedent and create a model for “community-supported housing.” They also want to demonstrate that a community of housed allies can care for people on the streets and in doing so, “break down the barrier between housed and unhoused people,” according to volunteer Ian Wilson. A significant aspect of the project is its desire to “change the culture of violence and disrespect towards homeless people.”

Ultimately, the group says that the city, in collaboration with homeless activists, should seize hotels, as well as the thousands of empty residential units in San Francisco, in order to fill the need for this housing. “There are empty units all over the city waiting to make profits for the title-holders, while people are dying on the streets, and that needs to change. Housing needs to be seen as shelter, not as monetary investment,” says Tyler Rougeau, an eviction defense lawyer and a founding member of Hotels Not Hospitals.

Shelby, 54, says that being able to stay in a hotel room for these past several months has “saved [his] life in more ways than one.” Giving one example, he describes spraining his ankle and how his injury was quickly exacerbated by sleeping on the street. “Staying in a hotel saved me. I think I wouldn’t have ever been able to walk properly again if I didn’t have the time to heal and be off of my feet.”

Even though his rental car was broken into the day he arrived in the city almost 10 years ago, Shelby “fell in love with San Francisco.” After a month of living here, he got a job cleaning boats. Shelby has a prolific social media presence on Facebook through which he solicits volunteers for homeless support projects—he’s currently working on an effort to help homeless people wash their clothes in laundromats, similar to the weekly Laundry Day sponsored by Rad Mission Neighbors.

Shelby has been on the supportive housing waitlist for two years. In the past year, 18 people that he knew personally knew died on the streets—of COVID, pneumonia and overdoses—including his best friend. “People helping people directly… it’s a hundred times better than the city. I don’t mean the city workers, because they are all very nice. But the city is just not effective.”

One source of frustration is the lack of oversight of the city agency responsible for directing homelessness prevention. In San Francisco, the decision-making power regarding the COVID response for homeless people lies with the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, the only major city department that does not have an oversight commission and instead reports directly to the Mayor. In 2019, District 6 Supervisor Matt Haney proposed creating an oversight commission for the department, but Mayor Breed objected that it would encumber the department’s work. Instead, the mayor opted to create a “working group” to perform oversight; That working group is closed to the public and has not met since 2019.

At the moment, the city has a historic opportunity to create permanent homeless housing. The solutions have been articulated; the funds are available (on the federal level through FEMA grants, on the state level through Project Roomkey, and on a local level through Prop C, which created a stable source of funds to acquiring homeless housing through corporate taxes); and the properties are available too—70 hotel owners have reached out to the city to indicate that they would like to sell. The model is there, the money is there, and the space is there.

The city has recently given money to non-profits who have acquired just two hotels for permanent homeless housing but the city has has not bought even one hotel itself.

San Francisco now has a greater opportunity to permanently house our city’s homeless – and end homelessness in San Francisco as we know it – than it has in years. The question is: will we do it?