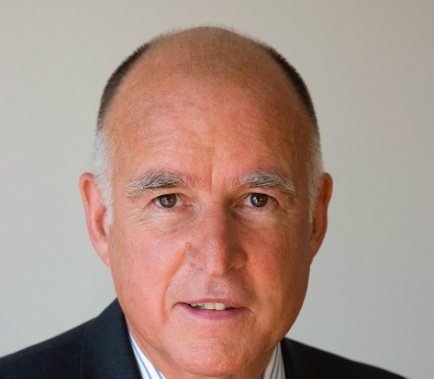

Scott Shafer’s conversations with former Gov. Jerry Brown are running as a series on KQED, and the section on his work in Oakland, which aired Sunday afternoon, makes very clear something that Brown’s critics (including me) have hinted at for years:

Mayor Jerry Brown didn’t care about poor people.

His words were shocking, except that they weren’t. For all his prior manifestation as a populist who blasted big campaign donors and fat cats, by the time he was running Oakland he was all about capitalism, down on government assistance, and a huge fan of real-estate developers.

At times in the interview he sounds almost like Donald Trump.

Brown told Shafer he wanted no affordable housing in the downtown area when he was mayor. His goal of bringing 10,000 new residents to Oakland was really about bringing 10,000 rich new residents. He said that if he allowed affordable housing, the people who lived there wouldn’t have enough money to spend in the upscale restaurants and entertainment venues he wanted to see spring up.

He said he didn’t want to require builders to add subsidized housing because “people who want the government to pay for their medicine and their housing, that’s not how we’ve been doing it in this country.” Yes: He said that.

He spoke of hearing from an African American woman who complained that his policies were driving up rents and forcing Black people out of Oakland. His response: Rents were going up because Oakland was getting more popular for rich people. That was a good thing.

In one of the more shocking segments, he seems to be defending the “riders,” a group of rogue cops who were accused of beatings, planting evidence, and a wide range of other offenses. The city wound up paying more than $10 million to settle civil suits in the scandal.

Brown first talked about how tough it was to be a cop, and how much he liked the OPD. Shafer pushed him and asked if he was defending the planting of evidence and police brutality.

Of course not, Brown said dismissively; those things were illegal. But he said that the cops were “at war,” that very bad people (at that point he sounded like Trump again) were trying to kill the police, and that, apparently, a bit of brutality was in order.

It’s pretty amazing. Except that for low-income people and people of color who lived in Oakland during that period, it’s not going to come as a big surprise.

City College is very much on the agenda this week: The supes will be voting Tuesday/28on whether to give the school the $2.7 million it needs to restore class cuts for this spring.

Mayor London Breed has shown no indication that she supports the supplemental appropriation, so it will need eight votes to pass with a veto-proof majority.

Critics – including the chancellor – are saying that this is just a band-aid, and that the school needs to downsize for the long term. But Leslie Simon, an Interdisciplinary Studies Department faculty member and former chair of Women’s and Gender Studies, said that’s the wrong approach: It’s a bridge, not a band-aid. By next fall, two ballot measures, one local and one statewide, will offer voters a chance to provide a steady stream of new revenue for the school.

Simon notes in an oped piece:

City College of San Francisco has been under attack for the last seven and a half years by conservative forces whose goal is to shrink the college. Education “reformers” seek to turn community colleges into junior colleges removing from the college’s mission “cultural enrichment, civic engagement, and life-long learning.”

Here is a sampling of what was cut for the spring:

Older Adults serving low-income elders lost 90 percent of its classes.

In the era of #Me Too, City College lost its last Women’s History class and both of itslast remaining self-defense classes. Art lost 51 classes and PE/Dance 45. Music, Journalism, Child Development, and Culinary Arts suffered serious losses. Engineering lost 40 percent of its classes

Paralegal Studies students lost the elective (Immigration Law) they needed to graduate from the college’s proud ABA approved program. The coordinator had to scramble to find the students classes elsewhere in the Bay Area.

Since enrollment reductions this year become permanent, cuts set the school in a downward spiral. Fewer classes means fewer students means less state funding – which means more downsizing.

Then on Friday/21, Sup. Shamann Walton, who is sponsoring the $2.7 million measure, has called a hearing at the Joint City, School District, and Community College Committee to discuss the impact the class cuts have had on low-income and communities of color and high-school students.

He tried to do this earlier this month, but none of the key people from City College (including the administrators and the trustees) showed up. The hearing starts at 10am in the board chambers.

The supes are going to vote Tuesday/28 on a settlement agreement in a law-enforcement-abuse case that would cost the city $160,000.

The case involves a boy who was arrested by SF police at 15 and held in juvenile detention in defiance not only of the city’s own risk-assessment tools but the orders of a Superior Court judge:

This case arises from the unlawful incarceration of K.R., an African-American teenage boy, in San Francisco’s juvenile hall. The San Francisco Juvenile Probation Department booked K.R. into the county’s locked juvenile facility on Thursday, June 29, 2017, overriding a risk assessment indicating that he should be released. On Friday, June 30, a judge of the San Francisco Superior Court ordered K.R.’s release. Officers of the Juvenile Probation Department received that court order, but failed to release K.R. Instead, the Juvenile Probation Department held K.R. in custody until the following Monday, July 3, when the judge again ordered him to be released.

As a result of the actions by the San Francisco Juvenile Probation Department, K.R. was held against his will in a locked cell, deprived of his freedom, separated from the care and love of his family, and subjected to the control of the custodial officers.

The city, as usual, will admit no wrongdoing in the settlement. But Bay Area Legal Aid says the case shines a light on a much more persistent problem: In more than 60 percent of juvenile cases in four Bay Area counties, authorities ignored their own rules and kept young people locked behind bars.

The new SF district attorney is likely to change that – although everything he does is getting attacked in the news media. The latest: Boudin has decided, for now, that he can’t charge Jamaica Houston with a crime while he is deciding whether the police officer who shot him also committed a crime.

That actually makes sense, from a legal standpoint: Boudin was a public defender, and he knows exactly what would happen in a trial if the prime witness against an accused assailant – the cop who shot him – is also under investigation (and potentially indictment) in the incident. The defense would shred that witness.

But Boudin didn’t just let a guy accused of assaulting a cop walk away a free man. The Chron has it wrong:

District Attorney Chesa Boudin, a former public defender whose election was opposed by the police union, decided not to pursue criminal charges against Jamaica Hampton, who was shot after he allegedly attacked two officers with a glass vodka bottle in the Mission District in December.

Boudin hasn’t decided “not to pursue charges.” He has withdrawn the charges without prejudice – meaning that any time in the next three years, after he has decided what to do about the officer-involved shooting, he can refile those charges.

And Hampton isn’t going anywhere anytime soon: He’s still in SF General Hospital, where he just had his leg amputated.

The Chron needs to stop feeding Fox News.