By Tim Redmond

DECEMBER 1, 2014 — You talk about housing in this city, you get lots of response. And when you suggest something as crazy as the notion that seniority ought to be a factor in allocating affordable places to live in this city, you bring out everyone. Witness all the comments on my last housing piece.

For the record: I am not serious in saying that decent affordable housing should only go to people who have been here 20 years. In fact, what I wrote was

If you’ve been in San Francisco for 20 years, and helped create and build this community, you have a right to stay here that trumps the right of someone with more money to move in.

The same should apply to someone who’s been here five years, or ten. Or two. You live here, you should have what in college we called “squatter’s rights:” It used to be a pretty well-accepted idea that nobody can force you to leave a place you rented legally, you pay for, and you take care of. Not except in unusual circumstances (the owner, for example, actually wants to move in).

What I’m really suggesting, though, is that we take a rather radical approach here, and ask some painful, honest questions — that start like this:

How do you allocate a valuable resource (affordable housing in SF) when demand greatly exceeds supply?

You can punt by saying: Build more supply. That’s the easy answer that everyone likes because it assumes that the free market works – and avoids the much harder issues. But let’s face it: Supply isn’t going to solve the problem. Certainly in the near term. We can’t possibly build enough housing in the next year or two to meet the demands placed on the city by the explosion of tech companies attracting high-paid workers from all over the nation – right now, today.

Right now, we need to solve the immediate problem. Then we can talk about the long-term issues.

And as I said last time we got into this, we need the tech community to help.

Ask the right questions

When you look at the city budget battles every year, you can argue that that city departments and services shouldn’t have to fight over scarce resources and the supervisors and the mayor shouldn’t have to make hard choices — because if we just taxed the rich there would be plenty to go around.

Maybe true, but again: That avoids the immediate challenge. Taxing the rich is hard in California. The underfunded mandate is huge – the city probably needs half a billion dollars a year to make up a structural budget deficit, and we aren’t going to get that from tax revenue in the next year. Right now, today, there isn’t enough money to go around, so how do we split it up? That’s what the budget hearings and discussions are about.

Same for housing: There isn’t enough to go around. We can talk about how to change that – and I will – but right now, we have a structural imbalance between supply and demand. How do you address that?

And my basic – and I suppose crazy, radical — answer for housing is: Not just on the basis of income and wealth.

Once you accept that concept – that the poor and the middle class have just as much right to live in San Francisco as the rich – and you accept a second concept – that the current situation is inhumane, horrible, unacceptable, and worse than just about anything else we could do — then you start looking for other solutions.

There is no perfect answer. But doing what we’re doing now – allowing speculators to toss out longtime residents just for quick profits, destroying communities in the process – is so bad that we’re beyond looking for perfect.

We’re looking for better. And we aren’t going to get there until we say that the current situation is so bad that almost anything – seriously, almost anything – would be an improvement over what we have.

Which means that the current system – driven by the private market – is so far from working that it’s more of a problem than a solution.

So I want to raise the question: How do you allocate housing by a means that is not purely economic competition?

How do you make sure that the critical necessity of life for long-term San Franciscans and their communities – that is, stable, affordable housing – is not destroyed by a cruel economic auction?

How do you balance the needs of the current residents who may not be rich with the needs of the well-funded companies that want a place for their workers to live that’s near where they work or near where the private buses pick them up and take them to work?

And is there a way to create a consensus around a housing plan that would serve everyone’s needs?

There are always welfare cheats

Whatever we come up with will be flawed. There will be people who cheat. When I started at the Bay Guardian a million years ago, the publisher, Bruce Brugmann, told me that you can always find a welfare cheat. Someone always games the system. If you let that drive your policy decisions, you’ll go the wrong way.

Most people on public assistance are not Ronald Reagan’s Welfare Queens. Most are barely making it. Pick one bad example and you undermine some very good programs.

There are people with rent-controlled apartments that can afford market-rate rent. You take those people and make them the poster kids, and you can argue that rent control needs “means testing.” I can take the same approach and say that many landlords are so rich they don’t need anywhere near the rent they’re charging; let’s means-test property owners and force the rich ones to charge less rent.

Those are pointless political games. There is an exception to every rule. You have to look at the overall picture, which is pretty clear: Most landlords are better off than most renters.

Again, let’s be honest: Rent control is a form of housing seniority. The longer you’ve been here, the better you do. If we had real rent control, like Berkeley had in the 1980s, then the price of a place to live would be set when it’s first rented and stay the same no matter how many people move in and out, but the state Legislature outlawed that.

So now we have the blunt-instrument: Long-term residents get a great deal compared to newcomers. That gives landlords some bad incentives – they want to rent to people who won’t stay long, and they want to get rid of long-term tenants. That is, if all they care about is profit.

I agree that the situation is unfair to some landlords. You have a tenant paying $800 a month for a unit you know you can rent for $5,000, and you feel cheated – especially if your friend down the street has an apartment where the old tenants died or moved out, and now she’s cashing in. The worst thing that can happen to you, I’m told, is to have your best friend get rich. You didn’t need a yacht until he got one; now you’re bitter.

But let’s remember that you aren’t losing money on the $800, since that price was set based on the value of the property when you bought it. You’re making money, just not as much as you could.

I repeat: The state of California has forced cities to make imperfect policy. And it was the landlord lobby that outlawed rent-control on vacant apartments and created this mess. Don’t blame me; I was on the other side.

So let’s go back to the problem: Too many people want to live in a small city right now, and there’s no room for them without forcing current residents to leave. Under today’s laws, current residents who are forced to leave by speculators and greedy landlords get no benefits at all; they’ve paid rent (and basically paid the landlord’s mortgage) for many years, but when the Ellis Act notice comes, they get a few thousand dollars (unless the Campos legislation survives in court) and a kick in the ass.

Facts are facts. Some people who work in San Francisco are going to have to live somewhere else, since there’s no way to build enough housing for the half-million commuters who arrive in town every day. So who decides which workers have to live in Stockton and waste four hours a day in transit — and which ones get to walk to work and have more time for their kids, for art, for music, for life?

If you let the current laws and private market decide, you are allowing a level of cruelty that is hard for anyone to justify. You’re also destroying the diversity of the city.

Some of the transitory nature of any city works itself out; some people want the extra space and the big back years and the culture that comes with suburbia, and are willing to pay the cost in transit time to get it.

But many more people – particularly young people – want to be a part of the very cool culture of San Francisco.

There are a limited number of housing units in this city that count as affordable; most of them are the existing rent-controlled apartments where tenants have been living for more than five years.

Pretty much everything that’s being built today is beyond the means of the vast majority of local workers. Maybe if we built 100,000 or more units, those prices would come down; I don’t believe it, but maybe. Could we do that without destroying the human-scale character of the city (Vancouver didn’t; the place looks like Hong Kong) and without demolishing the amazing historic architecture and diverse neighborhoods that draw so many people here in the first place?

There’s a fundamental flaw in the logic of the build-our-way-out crowd: The basic cost per housing unit in SF, I’m told, is $500,000 or more – and the private financiers demand such a high return on investment that no new privately built unit will ever go on the market for anything remotely affordable to the middle class, much less the working class Building 100,000 new units won’t bring down the price of land or construction materials. Build until kingdom come, and you won’t get places that sell for $300,000 or rent for $1,500 a month.

Another problem: We might very well wind up with 100,000 new condos for people who don’t actually live here.

And even if we decided to go that way, unless we went back to the bad old days of Redevelopment seizing property and bulldozing neighborhoods, it would take ten years. Maybe 20 years. Meanwhile: Evictions every day. Bitter fights over who gets to be here and who has to leave.

The Stockholm problem

If I could do it my way, and we had a housing lottery that took seniority into account, and people who have been here five years and wanted to start a family had more right to a bigger place than people who arrive last week, and people who have been here 10 years had more rights than that, and a lot of the new tech workers would have to live far out of town and accept the commute and the hotel workers and dishwashers who have been in the Mission for a long time would be able to move into nice hip flats with bedrooms for their kids, I think we’d have a better situation than we have now. Not perfect; nothing is perfect in a city under this kind of pressure. I said better, more fair.

In Stockholm, they have opted for fairness over capitalist opportunity; there’s strict rent control – and a 20-year waiting list for housing. That doesn’t work. The result: A lively black market in sublets. Lots of cheating, people selling spots on the waitlist, all sorts of things that undermine what the law set out to do.

That system, like ours, is imperfect. But at least the sublet money goes to tenants, not real-estate speculators. And the tenants have some choice in the matter.

I’m really lucky; I own my home. Bought the place 15 years ago when an alternative newspaper editor and a public-sector lawyer could still buy a house in this city. We never saw it as an investment; it’s the place we live, where our kids are growing up. These days, I’d be scared to have kids if I was renting; imagine trying to explain to a five-year-old why she was losing her bedroom, her neighborhood, her school, and her friends because her parents have less money than a tech worker who wants their apartment.

But as an owner, as long as I pay the mortgage on time, I have a choice. If Mark Zuckerberg wants to buy my house for millions of dollars, I can always say: No, thanks. I like it here.

If I’m a renter in a city with real eviction protections and a tech worker wants to sublet my $800 rent-controlled flat for $4,000, I can also say: No, thanks. My kids like their home and their school and their friends next door. Or I can do the math, say yes, and get some real financial reward for the loss of my home. My choice; not the choice of a group of speculators from Texas who care only about extracting cash from the SF market.

If I am a tenant whose landlord sells to speculators who use the Ellis Act to toss me on the street, I have no choice at all.

Is the Stockholm model perfect? Clearly not. Is it, overall, better than what we have in San Francisco? I don’t know. Because that gets into a much, much bigger question we will address in a moment: Do we have to plan our city around the needs of the current economic fad?

My analysis of the housing problem assumes, or course, that you accept what was once pretty mainstream thought but is now radical: The notion that a rent-paying tenant who takes care of the place and never violates the lease has the same rights to stay there as an owner, except in very unusual circumstances.

Is there a solution we can all accept?

I also realize that this is the United States, and it’s a capitalist society, and things you can do in Stockholm aren’t legal here. If we took 70 percent of the marginal income and wealth of the richest people in America, the way we did during World War II and the 30 years after, if we taxed corporate profits and prevented offshore tax havens, then there would be enough public money to buy up much of the available housing stock in cities like SF, and to build enough public housing for everyone who needed it. That’s the RIGHT answer to urban housing woes; it’s not a realistic one, not today.

So what can we actually do? Is there some kind of Grand Bargain that tech folks, who want a lot more housing, and housing activists, who want to protect existing communities, can all accept? There might be.

Let’s think about how it might look.

Community activists on the left would have to agree that the city is going to grow and we need to build a lot more housing. (I’m a bit shaky on this premise, see below, but I’m willing to compromise.) The tech folks would have to agree that the private market can’t possibly meet the city’s housing needs — and that all as much as possible of the new housing would have to be done through the public sector and nonprofits.

That, in other words, part of the answer to the housing crisis has to be removing housing as fast as possible from the private sector.

That should be fine, right? If tech firms want housing for their workers, they shouldn’t care who builds it. If new apartments are forever out of the private market, young engineers can still live in them. There’s just no money to be made buying, selling, and speculating in real-estate. Why should the tech companies care? They do that in the stock market. Different venue.

My commenters who are in the residential real-estate market say that rent control makes it unpalatable to own buildings in this city. I’m not seeing that; prices keep going up. But if we passed policies that brought down residential real-estate prices (yes, including mine), I wouldn’t be crying. The cheaper the housing, the easier for the city to buy it up, which is what could happen if landlords really decided to sell off in large numbers.

Here, I think, are some of the elements of a practical housing plan for San Francisco, something that could bring together well-meaning people across the spectrum:

First, do no harm. The evictions have to stop; everyone has to agree that long-term tenants can’t be thrown out to make way for better-paid newcomers. Tech money needs to fund a massive anti-eviction effort, from 100 new tenant lawyers or more to a new anti-spec tax to an agreement by all employers to ask workers to sign a pledge not to move into a unit cleared by eviction. Ron Conway has to join Erin McElroy on the picket lines every time there’s an Ellis Act notice. No candidate for any public office can accept a penny from anyone involved in evictions. We turn the Ellis evictors into social and political pariahs.

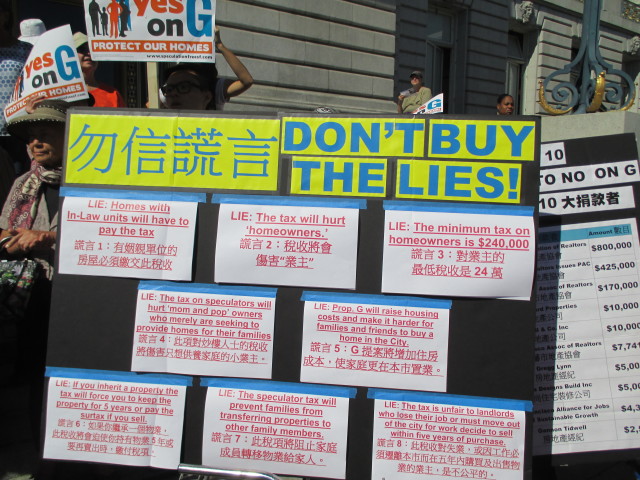

Not one tech mogul or tech executive gave one dime to the Prop. G campaign. With the kind of money Conway throws around on other issues, Prop. G could have won. Yes, Conway endorsed the reforms to the Ellis Act in Sacramento, but everyone know that was a long shot at best. He and his crowd have done nothing, zero, to help solve the problem right here in town. Come to the table not just with demands but with offers to help, and maybe we can all talk.

Eliminate other threats to the housing supply. Airbnb may have caused more problems for affordable housing in San Francisco than the Twitter tax break and the influx of high-paid tech workers. The current legislation won’t solve that problem. The city has to mandate that rental apartments are rental apartments, not hotel rooms. You have a spare bedroom you want to rent out to tourists? Great; apply for a permit to operate a Bed and Breakfast inn. City Planning gets them all the time. Most are approved. If too many come into one neighborhood, people will complain and the planners will have to slow down.

Oh, and the $25 million in back taxes that Airbnb owes would subsidize a lot of housing.

Something has to be done to stop the new housing from being sucked up by corporations and international travelers. A tax on non-primary residences is one option. That’s got to be part of the agenda.

Set a target for new housing at all levels – and let nonprofits build all of it. We need 30,000 new units? First, let’s make sure that’s a real figure, not something driven by short-term boomtown thinking. Is this tech growth real, for the next 10, 20, 30 years? If it is, let’s identify places where density can be increased (not just the Eastern Neighborhoods, and not just places where there are already low-income communities facing displacement). Then turn the whole thing over to the excellent, effective, proven nonprofit housing infrastructure that already exists in San Francisco.

If you assume a base cost of $500,000 per unit, a private developer will sell that unit for $1 million. A nonprofit only needs to get back the $500,000. At that price, a monthly mortgage payment is $2,881. Two people with middle-class salaries can almost afford that; it’s a lot lower than current rents.

Put up a modest $100,000 up-front public subsidy per unit, and use public land whenever possible, and those numbers come down to affordable housing for the middle class. Put up larger subsidies at the start and you can build housing for all levels.

Where does that subsidy money come from? How about tech agrees to support whatever taxes we need and can get on, say, commercial rents, development fees, non-primary residences is, transfer taxes etc.? How about every new office building gets assessed a realistic fee to pay for housing for workers?

And Ron Conway and his pals should help underwrite a campaign for a massive, multi-billion affordable housing bond act. That means higher taxes on homeowners; not perfect, but under Prop. 13, we all are getting a huge public subsidy already.

These tech folks are experts in the world of finance; let them come to the table and find the venture-capital startup money for a massive influx of public-sector and nonprofit housing.

Remember: This sort of development is sustainable. If nonprofits build housing and sell or rent it, they bring in revenue to do the next project. It takes upfront money, but not so much long-term money. If speculators and international investors can make a fortune on SF real estate, then there’s no reason the public and nonprofit sector can’t make it work, too.

Labor would like it; union carpenters, electricians, ironworkers, and plumbers make the same wage working for international speculators as they do working for local nonprofits. Building affordable housing creates construction jobs, too.

Could neighborhood folks accept a substantial new number of housing units and more density across the city if all of them were built outside of the private sector for the existing workforce? (And if they were sensitive to existing neighborhoods and weren’t horribly ugly?) Over time? At maybe 3,000 units a year? I think so. It’s worth a try.

I’d like to allocate those units by a lottery that gives precedence to current residents, by seniority. A couple living in a studio in the Mission who have been here for five years and want to start a family get a better shot at a two-bedroom unit than a young worker who just arrived. Of course, if the much-vaunted market works, that opens up their studio for the newcomer.

But we can’t legally do that. So we have to make a clear statement to the world: You want to move to San Francisco to take a job in a tech startup? Cool. But accept the idea that you might have to live a ways out of town, with a serious commute, when you first arrive.

I am told that some tech companies wanted to move to the East Bay, but their workers rebelled – they like living in the city where they work, because they don’t want to commute. Good for them. Lots of hotel workers and health-care workers and public-sector workers would like to live in the city where they work and not commute, too. And they have as much of a right as the software engineers. Back to my first point: Just because you have more money doesn’t mean you get that privilege. Maybe the Google buses need to create routes in El Cerrito and Richmond.

Use public money to buy existing affordable housing as quickly as possible and take it out of the private sector. In a housing crisis, the cheapest housing is the housing already there. It’s less expensive to save a rent-controlled unit than to replace it. If speculators can buy a four-unit building and flip it for a profit, the city ought to be able to buy it and keep it under rent-control and at least break even. Even at a loss, the city would spend less money buying buildings that now go to speculators, keeping them affordable, and avoiding evictions than it would trying to replace that housing with new construction.

I’ve never understood the reluctance to this concept at City Hall. You would think there might be creative solutions to making it easier and more affordable for the city to buy rent-controlled apartments. We gave Twitter a tax break to move here; how about we give property owners some sort of tax break if they sell to the city instead of to a speculator?

If we don’t want the city to be a landlord (and given our record with public housing, that might be reasonable), there’s an easy solution: The city just transfers every unit it buys into a community land trust, a limited-equity co-op or a nonprofit housing provider. Those already exist. We have demonstrated that the models can work.

Stop pretending that we’re an island. Why hasn’t anyone from the Planning Department, or the local tech leadership, or the Mayor’s Office, gone to Cupertino and Mountainview and informed the civic leaders there that San Francisco can’t and won’t be entirely and singularly responsible for solving the housing problem created by building massive tech campuses in places that build zero housing?

Could the tech leaders sign on to an agenda that gets them the new housing they need — housing that would actually be occupied by people who work in San Francisco, including their workers — but requires them to first help stop the evictions? Could they come to the table and say that, since the market has failed, public-sector nonprofit solutions are our only hope, and work with the community on that?

Could they accept the concept that they may be disrupting the economy but they don’t own the city and have to work with all the people who see this not just as an economic unit but as a community?

I hope so. I’ll go to those meetings.

Do we need all these tech companies?

The second question is equally interesting: Should we, and can we, slow down the influx of rich tech workers? The answer, of course is yes we can… If we want. We can simply refuse as a city and a region to allow the office space that attracts those workers. Cut off all new office space in SF, stop building tech campuses on the Peninsula, and the startups will go somewhere else.

We can argue whether that’s a good idea or not (I think it’s not entirely wrong to discuss it; when we passed Prop. M a lot of big companies—Chevron — moved out to Pleasanton, which incidentally put them closer to a lot of their workforce and took some pressure off SF. That wasn’t a bad thing. It didn’t destroy the local economy. You have to be careful not to destroy innovation and the local economy, but it’s okay to say: too much, too fast.)

The city has certainly gone the other way: SF has, as a matter of policy, done everything possible to attract more tech firms. If we hadn’t done that, some might have gone somewhere else. If we had a national industrial policy (how Commie of me!) they would be directed to Detroit and places that need the jobs and investment. Meanwhile, though, we can say that the carrying capacity of SF is limited and we can only handle so much influx.

Would the unemployment rate in town be higher if we hadn’t become Tech Central? Probably. But how much of that change is due to unemployed residents without tech skills leaving town and new people who come here from someplace else to take jobs replacing them? That’s not a program to improve the local employment picture. That’s a program to change the population.

We seem to have tremendous demand for office space in this town; for now and the forseeable future, tech people want to be here. Near Stanford, near Cal, near the VC world on the Peninsula … if we turned away some tech firms, slowed down a bit, I don’t think we would wind up as a ghost town without any innovative new employment.

Remember: San Francisco has been a dynamic, world-class city for 150 years. The top employers are not tech: Government, health care, and hospitality dwarf the digital sector. This city has so many advantages that it’s not going to hit the dark ages of Detroit and other economic disaster areas just because the growth of one sector of the economy cools from superheated to just hot.

In fact, superheated isn’t good for innovation; what the real creative people – artists, writers, and yes, programmers – need at first is affordable space to live and work. You can price yourself out of the innovation world – and we’re getting pretty damn close.

I guess what I’m making is a plea for rational, community-based planning. And for all of us, including the tech community, to join in.

Worth talking about anyway.