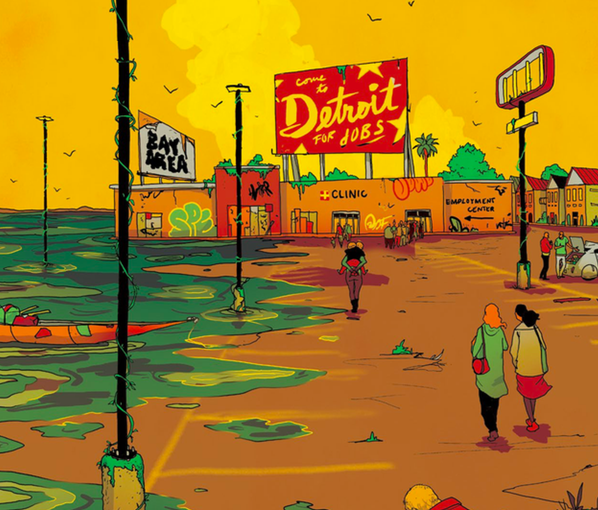

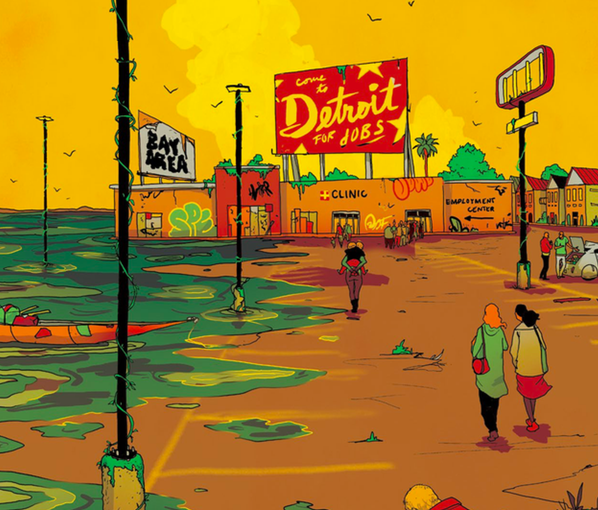

CNBC calls it a picture of a “dystopian future.” The Chron calls it a vision for “a better San Francisco.”

That’s what we get with SPUR’s provocative report on Four Scenarios for Bay Area, 2070.

The idea of the report: Project what the future could look like, depending on political decisions made by the voters.

I’m kind of amazed by the idea that more and more growth in a region that lacks the transportation infrastructure to handle the existing population, on the edge of the ocean in an era of climate change, is the best alternative.

But that’s how it comes down.

Three of the scenarios presented in the report are, indeed, dystopian. In one projection, the region becomes a “gated utopia” with a great life for a small number of very rich people:

But our collective choice not to expand the housing supply, nor to make investments in other public forms of social support, has pushed everyone except the wealthy out of the region. … Public transit is high-quality in urban downtowns, but most residents still take private transit, usually in the form of small autonomous vehicles summoned with an app. Travel is expensive because of permanent congestion pricing, but congestion has largely been solved in the core of the region.

Bay Area schools are good, with the distinction between public and private schools having blurred long ago. Everyone here can get a great education, but everyone who is educated here is already well-off.

Outside the core of the region, it’s a different story. Service workers endure long, crowded commutes from a sprawling supercity in the northern San Joaquin Valley that encompasses the formerly separate cities of Tracy, Stockton, Manteca and Modesto. Among its neighborhoods of inexpensive single-family homes, the supercity includes a number of shantytowns and tent cities.

Sounds horrible. How could such a thing happen?

A generation of middle-class people became multimillionaires simply through their luck in having bought houses at the right time. To make sure they hung onto their wealth, they exercised their power to prevent new housing from being built, and they elected leaders who opposed new housing construction.

Then there’s Bunker Bay Area:

The Bay Area has become a place of declining economic opportunity. Small pockets of wealth in highly manicured, highly protected neighborhoods are surrounded by slums — a pattern of extremes previously seen most often in developing nations.

There is little to no social trust or cohesion. Most people do not know anyone who is of a different class. There are virtually no pathways leading out of poverty. Many low-income people work in the informal economy of illegal products and services.

How did that happen?

As our focus turned inward, inequality metastasized. More and more of the region’s wealth ended up in a small number of hands. The shift was masked for a time by overall economic growth, but eventually there were simply many more people in poverty than not. We began to lose faith that everyone was in it together. Without a sense of shared fate, we abandoned the public realm.

We allowed those with money to control politics, which led to lower taxes and reduced the capacity of the public sector. We didn’t retrain people for new jobs or create the social safety net needed to keep up with the pace of economic restructuring.

We came to believe that the pie was not big enough for everyone. We accepted fear as a way of life.

And then there’s Rust Belt West. Pay attention:

With the admirable goals of supporting low-income workers and building inclusion, our activist communities took on big business — and won. This significant cultural shift has resulted in a strong sense of social solidarity, but as a result resources have dwindled and quality of life has suffered. Many residents experience an internal conflict: They support the values underlying the new policies but have grown cynical about the realities entailed in living with less.

While the Bay Area actively restricted businesses, other regions were courting them. Silicon Valley firms have moved to Seattle, New York, Austin, Shanghai, Toronto and Berlin. We have high unemployment and little to no new job creation. The Bay Area is no longer where the most highly educated workers choose to make a living; we’ve become somewhat of an economic backwater. As in Italy, our population grows older as younger people leave to find opportunity elsewhere.

How did this happen?

As the home of the American left, the Bay Area became increasingly radicalized. Over time, a series of new regulations made it increasingly difficult for businesses to function. A tax on stock options was so significant that startups had to leave the region before they could go public. Affordable housing requirements became

so onerous that developers could no longer raise the investment capital needed to build. As elected leaders competed with each other to show who was the most progressive, important protections for workers were taken too far: Minimum wage eventually grew to $75 per hour. Local hire laws made it hard to bring in workers from around the world, eventually regulating wages and restricting who could get red.The result was a vicious cycle: As companies left, there were no business leaders to contest the policy choices, which over time became more and more extreme.

But there’s hope. There’s another scenario that makes everything work for everyone:

In this scenario, the Bay Area has embraced the belief that we can grow the pie and divide it more equally. This principle of shared prosperity has led to high levels of investment in social housing, public transit, education and other foundations of an equitable society.

Fast and reliable transit, managed regionwide by a single rail and transit authority, provides the backbone of our transportation system, connecting to the lower-density parts of the region via shared autonomous vehicles, ebikes and new forms of personal transportation. Because we worked to bridge the digital divide, these services are available to everyone.

Our communities are designed to encourage walking and biking. Many neighborhoods have car-free commercial blocks like those found in European cities. Autonomous vehicles and drones deliver some of our goods, but the sidewalks are for people.

We welcome new people and new ideas, which has allowed a dynamic economy to prosper. Over time, some industries have gone away, but new jobs keep emerging as we continue inventing new things.

How did we get to this glorious future?

The residents of the Bay Area had to make some real sacrifices to bring about this outcome. Realizing that immigration politics were deeply related to housing politics, voters changed course on housing policy, reversing 30 years of neighborhood protectionism and allowing significant new construction.

Residents also voted to raise taxes on themselves repeatedly in order to fund social housing, public schools, public transit and other programs that helped bring about a high quality of life for people regardless of their income level.

People who had become wealthy in business were generous as philanthropists and invested heavily in the region. And businesses worked to develop a new employment bargain that translated the worker protections of the post-World War II era into a modern, flexible form with portable benefits, high investment in training and high wages.

As a result, the Bay Area population is much larger than people ever imagined was possible. It serves as a model of what a sustainable, prosperous, socially just metropolis can look like.

So let’s talk about all of this for a second.

When we talk about a “socially just” metropolis, I think about Susan Fainstein, the Harvard professor of Urban Planning who wrote the definitive book on “The Just City.” Fainstein makes a distinction between equality and equity; equality means everyone gets a level playing field, and equity means people who start off with less get a boost.

She also says: Equity is, by definition, redistributive. Equity in a Just City means that the government takes from the rich and gives to the poor.

Redistribution is not done by philanthropy; it’s done by taxing the wealthy.

With that in mind, let’s take a look at some of these scenarios.

Scenario One is actually starting to happen. But it’s not in any way the result of homeowners electing leaders who opposed housing construction. It’s because we’ve elected leaders who decided that it was a great idea to give tax breaks and benefits to attract tens of thousands of new tech workers to move here from somewhere else with no plan whatsoever for where they would live. Then we elected leaders who thought that building housing for rich people, many of whom won’t actually live in that housing since it’s just an investment, would solve the problem.

That didn’t work.

Scenario Two is about a loss of civic engagement – and that’s linked not to losing “a sense of shared faith” on the part of the general public, but to a dominance in politics by a small, very rich, elite, people like Ron Conway who care more about their own profits and wealth than about the common goal of a livable community.

Scenario Three is, I guess, aimed at people like me. It’s the idea that, by using local authority to make demands on the rich and big business, we have ruined everything.

And of course, Scenario Four is about how we all came together to reverse “neighborhood protectionism” and “voted to raise taxes on ourselves” to create a much larger, denser, and socially just Bay Area.

Scenario Five – in which large parts of the Bay Area are underwater in part because of the decisions that lead to Scenario Four – is not discussed.

John Elberling, the director of TODCO, offered his own scenario:

A New Social Hierarchy – People First

Egalitarian sentiment has gained ascendency in the Bay Area of 2070, causing human values to be given equal priority with wealth creation and concentration, and economic growth to be in balance with urban capacity and community stability. As a result the Bay Area becomes the most desirable place to be in the USA, but conclusive protections for vulnerable/disadvantaged populations and communities maintain their integral presence and enhance their prospects.

ECONOMIC/URBAN SUSTAINABILITY + SOCIAL JUSTICE

With the progressive goals of supporting lower and middle-income communities and protecting vulnerable populations while building social inclusion, our activist communities took on big business, entrenched property wealth, and market/investment capitalists – and won! This significant cultural shift has resulted in a strong sense of social and civic solidarity with the empowerment of all communities as equal stakeholders in the future of the Bay Area. As a result, all resources – housing, transit, infrastructure, etc. – are in balance with continued but moderated economic growth. Many of the region’s elite, however, experience an internal conflict: they support the values underlying the new policies but are unhappy at not running the whole show for their own priority benefit anymore.

HOW WE GOT HERE

As the home of the American Left, the Bay Area became increasingly progressive. Over time, a series of new regulations linked the rate of economic growth to the capacity of the Bay Area’s housing and infrastructure to match it. New local taxes on big business and property wealth to fund vital safety net, education, and public services significantly made up for the collapse of Federal support due to control of national policy by a self-enriching American Oligarchy. A substantial fraction of the wealth created by urban growth was re-captured – and increased by significant densification of suburban business districts especially – to address the negative consequences of growth, achieving a 50 percent affordable housing production share and stable Central City communities along with functionally adequate urban infrastructure. Important new protections for workers stopped their ‘gig economy’ exploitation and offset the impacts of work automation. Minimum wages grew to enough to actually live on.

The result was a virtuous cycle. As the Bay Area became the most desirable place in the USA to be, the most socially open and diverse, with the most accessible and uplifting quality of life for all its people, that enormous added societal value induced its many economic actors, large and small, giants and start-ups, to remain and continue to invest in its future despite the premium costs. We all learned to care about each other.

I like that one better.

I had a long email discussion about this with Gabriel Metcalf, who is the principal author of the study and the outgoing director of SPUR. I started with this:

- Do we really have to “sacrifice” and tax ourselves when all of what you call for would be possible if we just taxed the great wealth in this city and state at a reasonable rate? The report says nothing about taxing the rich, only about asking them to be philanthropic — which isn’t going to pay for high-speed rail. Why is that?

- The whole assumption of the report is that we have to grow or wither away. We all talk about environmental sustainability; why not a “sustainable” economy that survives without constant growth or retraction? Isn’t that both possible and desirable? (As Sim Van Der Ryn once asked me, “why do we have to have a perpetually adolescent economy?)

3. What do you think about the scenario that John Elberling posted?

Here’s his response, unedited (except for clarity):

Metcalf: First of all, there are probably many, many different scenarios that people could develop. Elberling wrote up one, but I’m sure we could come up with a lot of others too. There’s nothing “correct” about any of them, it’s just an exercise for thinking through possibilities — how current forces or trends might develop over time, how we might respond to things, how our efforts might turn out if they were fully realized, etc.

In terms of the specific things you are asking about, here are some things that we tend to give a lot of weight to in our thinking about problems and solutions for the Bay Area:

- Many institutional and policy ideas that work on the scale of a country do not work well at the sub-national scale. We spend a lot of time at SPUR thinking about the question of geographic scale — the pros and cons of doing different things at the scale of the city, the country, the state, or the federal government.

In some cases, it’s perfectly fine to implement something at a sub-national scale, even though it would be better to do it at the national scale. An example is California’s renewable portfolio standard. It would have much more of an impact if the US as a whole had an RPS for the entire energy sector, and there are some downsides to doing it at the level of individual states having to do with shifting the location of energy-intensive industries, but the pros clearly outweighs the cons. There are lots of other examples where that old concept of the states as the laboratories of democracy (testing out ideas that can be copied or scaled up) really works.

But there are other cases where an idea that works at the national level does not work well at the local or state level. For me some of the big social-democratic tools of tax policy and employment regulations fall into this category. Basically, I think most of the work of redistributing wealth through taxes has to be done at the national level. It’s simply too easy to shift the location of activity, especially the location of business investment, but potentially residential location as well, to avoid taxation.

Of course, state and cities can (and do) have their own taxes and rules on business. But these local costs have to be counter-balanced by the added value of being in a place, relative to the other options. Places like New York and San Francisco can (and do) have higher business taxes than almost anywhere else in the US but there are limits.

There are also other dynamics related to mobility of people and firms that make some policies not work well at the sub-national level. Another example is health care. I worry that as Red and Blue America move further apart on health care, there will be a cycle of adverse selection where the sickest people have to move to the Blue states, which means that the health care systems of those states will have to bear much higher costs. Canada, which gives the provinces quite a lot of autonomy in designing their own health care systems, has federal requirements on the standards those systems have to meet, in order to prevent these adverse selection dynamics.

The social-democratic construct of taxing rich people and using the money to provide a basic level of well-being for everyone (either via direct income transfers or by providing for key needs like health care) works much better at the federal level. It’s quite unusual for people to move their country of residence for tax reasons, but it’s quite common for people to move within a country.

- In terms of taxing business activity, personal income, wealth, or other things:

We observe that a lot of the social democratic countries seem to have low businesses taxes and high personal income taxes. I can’t vouch for accuracy of wikipedia on this topic but if these are close, I think it’s an interesting comparison. Sweden, Finland, Germany, Canada, the Netherlands, Switzerland… they are all within a pretty similar range of business tax levels.

This makes intuitive sense to me as a good way (certainly not the only way) to structure things — a tax structure that would help generate a lot of wealth, but then ensure that the wealth is more equally distributed. And I guess we were trying to imagine one way of working out that idea in our New Social Compact scenario.

So, there is reason to think that at least one type of social-democratic society is built on relatively low business taxes with relatively high personal income taxes.

But I think the best thing of all is to tax wealth, rather than income. With the many pieces of evidence that wealth is now more unequally distributed than income, we really need to be taxing wealth if we want to make progress on inequality. And the biggest source of that is property. This is one of many reasons that Prop 13 is so pernicious in its effects.

I am, like many planners, very influenced by Henry George on this. Much of the Bay Area’s wealth is being channeled into land rents — money that goes to incumbent property owners in the form of rising home values or literally rents they collect.

Taxing property to fund public infrastructure (and public services) also has a big advantage in that it is a non-mobile factor of production, so the induced behavior changes are less problematic than taxing many other things.

To build the kind of society we want will take a combination of funding measures, but of the big traditional sources I would personally lean heaviest on property, second-heaviest on personal income, and third-heaviest on business activities.

-

On the idea that we have to grow or wither away… yeah, I think that’s a good point. My own preferred scenario involves high levels of economic growth and coupled with high levels of equality. There’s a lot of reasons I prefer that scenario, including the goal of giving lots of people the opportunity to live here and experience everything that is good about the Bay Area’s culture. But yes, other people could develop their own scenarios that do not involve economic growth. There is, as you know, a big literature on “steady-state” economies as a goal.

Me:

Thanks, Gabriel. I guess where I disagree is that we can’t impose some of the social-democratic ideas at the local level. In fact, I think we have to, or we are all doomed. Washington (unless Elizabeth Warren is elected president with a far more radical Democratic majority in Congress than we have had in my adult lifetime) isn’t going to do it. Gavin Newson and the CA Legislature? We both know better than that. The only hope we have for fighting economic inequality is in cities. It’s harder, and on a pure theoretical policy level, it would be better to do on a national scale, but I fear that unless some really astonishing changes happen really fast on the national political level (including the repeal of Citizens United) or the robotic people figure out how to keep me alive till I’m 170, I will never see that happen in my lifetime. I fear my kids won’t either.

Unless we can start and make it work in cities.

I would love a city income tax in SF. State won’t allow it. I would love higher property taxes in SF (and I say this as a homeowner who benefits immensely from Prop. 13). Good luck getting that repealed. But this city today has greater wealth than possibly any city in the history of civilization, and we need to recapture some of that to solve our local problems. And the best way to do it is to go where the money is — the very wealthy, the biggest landlords, the biggest businesses. I promise you, Make Benioff won’t move Salesforce out of town if he has to pay a tiny fraction more in taxes. He doesn’t want to live in Texas, either.

Metcalf:

Yeah, I think this is the right debate to be having.

I know you know this, but I’ll just say it: just because something is blocked at the national level doesn’t mean it will work well at the local level. As one of the intellectual leaders of the SF progressive movement, I think you could really help people sort through that — to think through potential unintended consequences and help make those judgement calls.

I guess I’ll also say, sort of in the spirit of parting free advice as I look at my last few months in this role, I think it would be good for you guys to have a theory on how high various taxes should go. When you can assume there will be powerful push back from the other side, then you don’t have to self-regulate that — you just push for as much as you can get. But there will be times in SF (maybe at the State level too?) when you have enough power to get whatever you push for. Knowing where the line is would be helpful.

As a secondary matter, it would probably help some of the more progressive parts of the business community form an alliance with progressives, if they believed proposed tax increases were not infinite, with one more measure at every election until the end of time.

My own theory on taxation says that the property tax can go quite high, and it’s the one tax that is low, low in California compared to much of the US. I understand the political problems with it, as you point out. But I do think the overturn window on Prop. 13 reform is moving, and there are various ways to get money from property wealth that don’t involve reforming Prop 13 (transfer taxes, GO bonds, Mello Roos districts, etc.)

The real debate we’re having here seems to be whether local government in a place like San Francisco ought to be doing what the federal government won’t – and whether growth is always a good thing. It’s also about who decides: Who dominates local politics, who puts up money to win elections, who are the plutocrats who dominate the back rooms.

Right now in San Francisco, that tends to be real estate and Big Tech.

Those industries and the people who lead them are overwhelmingly interested in short-term profits. They have immense wealth. They have, to a great extent, received major tax benefits under Trump – that is, they are paying the federal government a lot less tax money than they were a year ago.

It’s hard to imagine any local tax coming close to recapturing that money.

They are not going to leave San Francisco because of local taxes, a reasonable minimum wage, or regulations on their business models – and if they do, the city will survive. In fact, if ten percent of the tech companies in SF moved out tomorrow, the city might be better off: The pressure on the housing market would be reduced.

This is, and always has been, an entrepreneurial town; it’s also a town where government, health care, and tourism are the biggest job generators, and the idea that people will stop wanting to visit SF because tech companies moved somewhere else is nuts.

In fact, if the pressure on the housing market dropped, we were able to put more homeless people into housing, the traffic wasn’t as bad, and the streets were cleaner, tourism would go up.

Oh, and about the $75 minimum wage? We’re talking 50 years from now. If the minimum wage had been $15 in 1968, 50 years ago, it would be $108.62 today. So that scary scenario is actually looking at a real reduction in the minimum wage.

Which isn’t going to drive anyone away.

My fear for the future is not that San Francisco will become the next rust belt; my fear is that it large parts of it will be underwater, that the Big Tech and real-estate plutocrats (not homeowners) will turn it into a gated community of the rich, and that we won’t learn that the answer to the housing crisis – and to the whole idea of a Just City – starts with equity.

And that, I will agree with Metcalf, includes taxing wealth — but the biggest wealth in this town right now is not homeowners whose property values have gone up (although their income may not have, and the may have no incentive to sell their homes). It’s tech stock options, speculative real-estate investment, and developers. The biggest beneficiary of the Twitter tax break wasn’t Twitter; it was the Shorenstein Company, which owned the building Twitter now occupies.

You want to tax wealth? Go where the money is.