By Zelda Bronstein

OCTOBER 13, 2014 — Every month, the law firm of Reuben, Junius & Rose hosts a lunchtime forum called the Real Estate Roundtable at the City of Club of San Francisco.

(Regular readers of 48 hills will recall the company’s aggressive representation of the owners of 660 3rd St., who’d illegally converted their industrially zoned property into tech offices, and with principal Andrew Junius’ recent attack on Supervisor Jane Kim’s proposed interim moratorium on PDR-into-office conversions in SoMa.)

The speaker at this month’s forum, which took place on Oct. 9, was Gabriel Metcalf, executive director of SPUR, formerly known as the San Francisco Urban Research Association, the urban think tank. Metcalf’s topic: “Peace in Our Time? Will San Francisco’s Growth Wars Ever End?”

The title alone, with its paraphrase of Neville Chamberlains’ infamous 1938 pronouncement about the Munich Agreement with Germany, was worth the $65 price of admission to the lunch, and 48 hills sent me on assignment.

I’d never been to the City Club; indeed, Berkeley provincial that I am, I’d never heard of it. Opened in 1930, the lavish, 11-story art deco building originally housed the offices of the stock brokers who worked on the trading floor of the adjacent San Francisco Stock Exchange on Pine Street. Its noted architect, Timothy Pflueger, believed that great architecture should have art to match. Accordingly, he commissioned the leftist artist Diego Rivera to create a mural for the stairwell joining the tenth and eleventh floors. The choice was controversial, but according to the City Club’s website, Rivera’s 1931 work, “Riches of California,” became “the centerpiece and the symbol of [the place].”

But the whole building is spectacular, including the Main Dining Room on the eleventh floor, where about 50 people gathered for this session of the Roundtable. The back of the program listed representatives of the companies that had signed up for the event. Heading up the roster, which included many of the biggest developers and most prominent attorneys in San Francisco, was 48 hills, followed by my own name.

Well, no

I never did find out whether Metcalf had consciously invoked Chamberlain. But right off he answered the question posed by his talk’s title: “Probably not.”

“I am told,” he said, “that the Coalition of San Francisco Neighborhoods may require any upzoning to be voted on.”

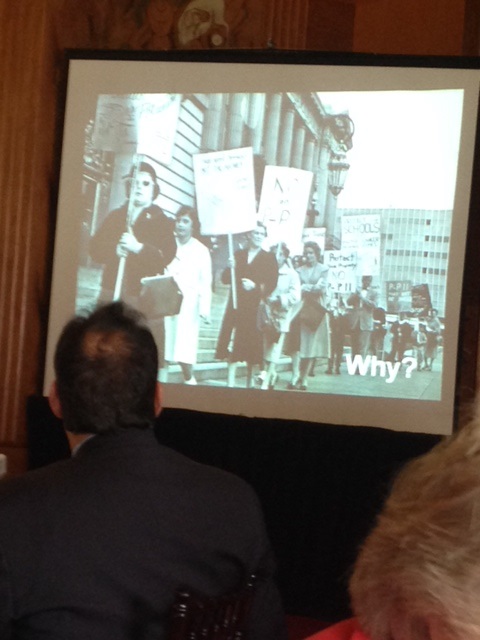

Metcalf then launched into a PowerPoint-supported survey of the city’s slow growth movements. First up was a 1984 page from the Bay Guardian that sported the headline “Is it still your city?” “This,” he said, “has been going on for a long time.”

His big question: why?

He partly attributed San Francisco’s persistent grass-roots opposition to development to the traumas resulting from a series of mid-century development disasters: freeway expansion and urban renewal.

Trained as a planner at UC Berkeley, Metcalf dissed his professional forerunners: “The developers came in with their plans and tried to destroy the city.” He illustrated that statement with photos of the catastrophic devastation in the Fillmore and the protests over the demolition of the International Hotel.

“But every city,” he observed, “had freeways and urban renewal….and its reformers that stopped it. By the mid-1970s, no one was doing this any more.” And, he maintained, no one ever would: “Planners in America will never be given power again because they blew it.”

This was where San Francisco’s history went off on its own tangent. “Many cities started growing again….Why should the growth wars in San Francisco have taken such a different course?” Why, unlike in other places in America, did development remain the “dominant political issue”?

“Was urban renewal in San Francisco more devastating than in Boston or Chicago? Is there something different about our activists?”

Seven ways to peace

Confessing that “I don’t totally know the answer,” Metcalf proceeded to offer what he called seven “theories of peace:”

1) The outlook for development is cyclical, actually doubly cyclical, with the business cycle and political cycle moving in tension with each other. During a boom, voters are anti-growth; during a recession, they’re pro-growth. There’s “a brief period when politics will allow building and you can get a loan. Usually when the politics allow [development], you can’t get a loan.” As this theory would indicate, “we’re now in the middle of an anti-growth backlash.”

2) Consensus can be built through careful planning—for example, the Transbay Terminal (not careful enough, it would appear) and Rincon Hill. But such efforts take 10-15 years and longer to reach fruition.

3) Deals that include high levels of affordability are achievable. The examples here are Mission Bay, Trinity Towers, Parkmerced, and the Shipyard. “Many of the equity activists like this template best. Nobody has tried to undo Mission Bay.” (But Mission Bay did not rise up at the expense of an existing neighborhood. It was built on empty land.)

4) “If it gets bad enough, people will accept change.” This, Metcalf said, is something he “hear[s] at cocktail parties.” He cited the new, pro-development Bay Area Renters Federation (BARF).

5) “Win the argument.” Smart growth, the model championed by SPUR and Greenbelt Alliance, prevails. “Not going to happen.”

6) “Lose the argument.”

7) Fashion a “grand bargain,” exemplified by the Downtown Plan. It “stuck until the Downtown was fully built out. What,” Metcalf asked, “would a new grand bargain look like?”

Metcalf then opened up the forum for discussion.

Jeffrey Heller, President of Heller Manus Architects, said that in the 1980s he was visited at SOM (Skidmore, Owings and Merrill) by “a young Sue Hestor” who was then working for Alvin Duskin. Paving the way for Prop. M., Hestor originally proposed that an 80-foot height limit be imposed on the entire city.

I surmised that the point of this anecdote was to demonstrate the draconian nature of the city’s “equity activists.”

Heller then offered his own list of answers to the question, why is San Francisco different?

1) Hippies: they came here seeking quality of life, and they stayed.

2) “Commies”—specifically, Calvin [Welch], who “truly believes that supply and demand does not work” and that “we should be doing only affordable housing.”

3) CEQA (California Environmental Quality Act): “I’m in the trenches,” said Heller. “Can’t do a damned thing.” We “met with [Darrell] Steinberg” about reforming [i.e., eviscerating] CEQA, and he “double-crossed everybody.” Compare New York City, “which doesn’t have CEQA.”

4) Protecting the neighborhoods. “That’s great, but we have a limited supply of land.”

5) The Downtown Plan: “What we did was really a preservation plan,” and ultimately that’s not going to sustain development.

6) “The city’s gone global.” Heller just returned from China. “Everybody who doesn’t want to invest in Europe,” he said, “wants to invest in New York and San Francisco.” That puts “enormous pressure” on our real estate values. “Beijing is horrible; everybody wants to be here for the quality of life. Maybe the hippies are right.”

Metcalf then offered his familiar (to readers of the Chronicle and the SF Biz Times) argument that if you add enough housing, prices will go down. “Even the left, he averred, “would agree.” We could build enough to make that happen. But people think “we shouldn’t, because protecting the character of the city is more important.” Those prescient hippies again, I thought.

But Metcalf was not about to salute hippies, even in jest. Instead, he trotted out the Kim-Mai Cutler argument: “Can you be a progressive person and think it’s okay to tell other people you can’t be here? I don’t think so. That’s not an ethical stand.” San Francisco voters are “liberal,” so how do they justify that exclusionary attitude?

Junius asked about building affordable housing. “As Jeff said,” Metcalf replied, “many early affordable housing advocates were actual Communists.”

And Metcalf does recognize the city’s affordability crisis. Marking the “failure of public housing,” he noted that the money to renovate Sunnydale, Potrero and Hunters View is $1.9 billion short—and the needed funds aren’t going to come from the federal or state government. He’d like to see the voters pass an affordable housing bond.

Changing Prop. M

Next up was the urban planner and consultant Paul Sedway, who asked about the mayor’s proposal to modify the Prop. M cap, noting that “some of you [here] are intimately involved in this question now.”

Metcalf responded: “There’s a lot of hope that we might have made a little administrative error.” He was referring to the fact that some big office projects have been converted to residences—for example the former AAA office on Van Ness. “A small technical fix would allow a couple of buildings to be constructed.” But that would hardly address the millions of square feet of office space that are either in the planning pipeline or developers’ sights. “A reasonable compromise,” Metcalf proposed, “would raise the cap a bit in exchange for money for affordable housing.” In any case, he said, “you can’t have the kind of system where prices go down.”

The most intriguing comments about Prop. M came from Carl Shannon, managing director of Tishman Speyer’s San Francisco office. From 1987 to 1990, he said, Prop. M was enforced. From 1990 to 2014 the measure had no impact on what got built. Now there’s an incredible “upward pressure on rents” that’s affecting two kinds of tenants very differently.

For the tech industry, Shannon said, rent is “irrelevant. They will pay the highest rents”—whatever it takes to build the facilities needed to attract the best talent. Architects, lawyers and accountants are in a very different boat. “Every law firm in town is looking at moving back office functions out of the city.”

And then, near the end of the forum, this revelation: Shannon said that he and other office developers had just “sat with [Planning Director] Rahaim and [Director of the Mayor’s Office of Economic and Workforce Development] Rich” and talked about raising the Prop. M cap. “These guys,” he reported, “don’t even want to talk about it. The city attorney doesn’t want to weigh in on this. They’re afraid of the political ramifications from the other side.”

* * *

I walked out of the room with my head spinning, exasperated by the problematic renditions of political reality and history.

Some of the problems involved errors of fact.

Sue Hestor worked for Duskin on height limits in the early 1970s, not 1980.

The Downtown Plan was no “grand bargain” agreed to by all parties. Devised under Mayor Dianne Feinstein, the biggest booster of unlimited office development in modern San Francisco history, the plan was bitterly opposed by the slow-growth advocates. Passed despite them, it helped lead to Prop. M.

I’m sure the developers’ frustration with Rahaim, Rich, and Herrera is genuine, but it’s at odds with indications that City Hall is seeking ways to lift the annual cap on office development.

The main reason Mission Bay hasn’t sparked protest isn’t that it includes affordable housing but the fact that it didn’t rise up at the expense of an existing neighborhood; it was built on empty land.

Then there was what sounded like red-baiting. On Friday, the day after the forum, I asked Metcalf exactly to whom he was referring when he said that some of the early affordable housing advocates “were actual Communists.”

His response, by email: That was just a “dumb quip.” Fair enough, we all do that sort of thing.

Metcalf went on, however:

As I’m sure you know, the early planner[s] and the early housers were very much of the left and very much aligned with various shades of socialism or communism. I knew many of them as I am guessing you did too. They believed that ‘planning’ as a discipline should be not just be about physical planning as it is today, but also ‘economic planning. These were the people that reorganized SPUR into its “modern” form in 1942, and these were the people who fought for public housing.

Metcalf’s version of SPUR’s founding doesn’t jibe with the account provided by the eminent scholar, Chester Hartman, in City for Sale, the classic history of land use politics in San Francisco since the 1950s.

According to Hartman, SPUR was “father[ed]” in 1959 by the Blyth-Zellerbach Committee, which had been formed in 1956 by Blyth, “a prominent stockbroker and director of the Hewlett-Packard electronics firm, Crown-Zellerbach Corporation, and the Stanford Research Institute,” and J.D. Zellerbach, “the pulp and paper magnate.” Hardly socialists or communists—or even liberals.

“SPUR,” Hartman wrote, “was devised to openly generate more ‘citizen’ (meaning business( support for urban renewal in San Francisco.” In fact, from 1959 to 1977 the R in SPUR originally stood for Renewal.

Finally, there was Heller’s nomination of Calvin Welch as a “Commie” and accompanying equation of Communism with a disbelief in the functionality of supply and demand in the San Francisco housing market. Now we’re dealing with ideology as well as facts.

Welch does believe that in San Francisco, supply and demand cannot provide affordable housing –and he’s hardly alone in that view. There are plenty of mainstream, non-Commie types who agree (one of the most outspoken of them is Doug Engmann, an options trader and venture-capital investor who used to chair the Planning Commission).

Granted, the city’s economist, Ted Egan, says that housing prices would fall if 100,000 new units were built. Can San Francisco’s infrastructure and public services—starting with firefighters and police—and budget really support that kind of growth?

Which brings us to Metcalf’s charge that it’s unethical for progressives to deny anyone who wants to live here the right to do so. I don’t get the connection. But I do get the basic assumption: that unlimited growth is a good, especially in a place that has both too much and too little water. And that’s just the start of the trouble with the “growth is good” agenda.

You have to wonder if the real-estate people in the room – many of them nice people, smart people, not evil people – have any clue what it’s like to be a senior citizen or a person with AIDS or a Latino family evicted from the city because “supply and demand” hasn’t built you an affordable housing unit – and never will. Or to operate a small business in light industry that’s being forced out of town (and maybe out of business) because tech office developers and the city’s planners think your land is too valuable for blue-collar work.

Thanks to the efforts of the city’s wide-ranging community activists, until people who already live here and have been here for a long time, aren’t forced out by rocketing real estate values and and official dereliction, there will be no peace in our time over the land wars in San Francisco.

On this one, I’m with Metcalf.