Groundbreaking 2012 arts festival — which fought Lee’s “art washed” gentrification plan — is revisited with new book and two events, Thu/15 and Fri/16.

By Marke B.

ART LOOKS How do you throw a sprawling, thought-provoking, renegade art fair to protest the gentrification of a neighborhood — just as the mayor starts pushing art fairs as the key to sugarcoat his gentrification agenda?

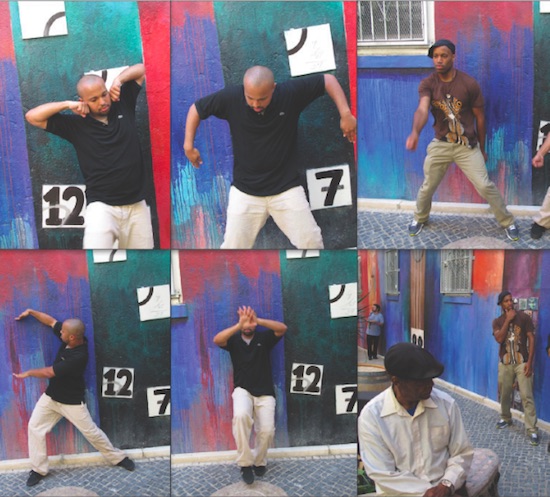

That’s one of the contemporary arts dilemmas the organizers of the 2012 Streetopia festival — which occupied Mid Market and Tenderloin abandoned storefronts, public spaces, and civic-minded galleries with work from almost 100 artists and activists — set out to explore.

Their creative approach? Double down on community engagement, dig deeper into San Francisco’s communitarian past, activate spaces left abandoned by rampant speculation, and challenge participating artists to harness the abstract to the concrete to address and broadcast the concerns of the local population, caught up in a seemingly uncontrollable wave of change.

A free food cafe, a geography-based project informing homeowners of the hippie commune past of their property, public interactive performances, and more were meant to counter the “art washing” that can take place when art fairs like Art Basel Miami take over a community and contribute to its displacement.

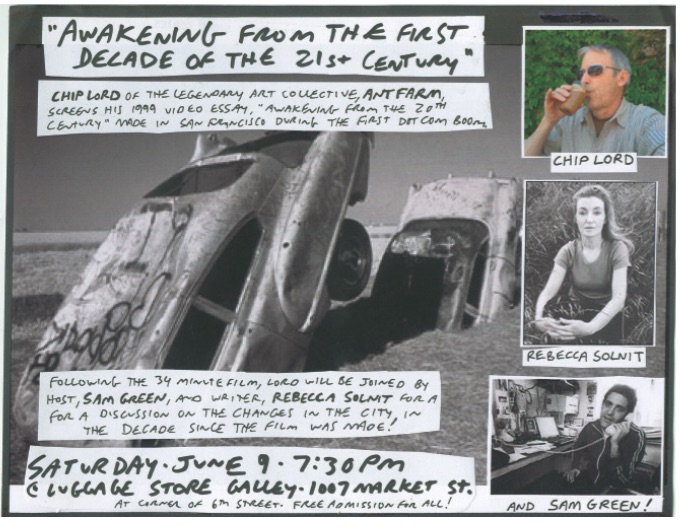

Three years later, Streetopia is back — in the form of a new book documenting the festival with full-color pics and 24 in-depth essays from Bay Area arts heavy-hitters like V Vale, Kal Spelletich, Chris Johanson, Barry McGee, Spy Emerson, and Bochay Drum that address Streetopia’s vision, execution, and legacy. A panel with the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (Thu/15) at Adobe Books and a full-on bonanza book release party (Fri/16) at Luggage Store Galley — locus of the original Streetopia — will bring this vital piece of recent history to life.

I talked to Streetopia fest co-curator and Streetopia book editor Erick Lyle about the legacy of the festival, the implications of large arts organizations like Burning Man establishing shiny new bases in the Mid Market and Tenderloin areas, the idea that arts can “clean up” these supposedly “blighted” area, and how art can actively address gentrification and change.

48 HILLS The conditions under which the original Streetopia took place in 2012 were incredibly fraught and interesting — Streetopia risked being co-opted as the very thing it was set up to draw attention to and resist. Can you tell me a little about that?

ERICK LYLE The gentrification of the Tenderloin and Mid Market areas has not just included Ed Lee’s “Dot Com Corridor” but Lee’s execution of Newsom’s older plans for a Tenderloin Arts District. After two decades of gentrification and rising rents driving an enormous amount of artists from the city, Lee and Co. have sought to instrumentalize the remaining arts groups in the city into forces for gentrification by urging them to relocate in the city’s last low-income neighborhoods.

In other cities around the world, municipalities have sought to spur gentrification by luring the so-called “creative class” into low-income areas to bring redevelopment and displacement. Specifically, the form of the art fair has been strategically used by bring the corporate and increasingly homogeneous brand of the art world to hyper local places like The Tenderloin. Its not difficult to imagine city planners dreaming up an art extravaganza for the neighborhood to lure displacers into the area!

But Streetopia was specifically about asking artists to choose a side: do they want to simply shrug and accept the benefits of gentrification at the expense of the existing community in the TL? Or do they stand with that community and make art that can amplify the existing strengths of the community and counter the negative media image of the Tenderloin while helping to organize people to fight back?

The Luggage Store Gallery has to me always been an example of an arts group that has a true community focus. The group has worked for decades to develop programming and projects that benefit the already existing community in the Tenderloin and that improves the quality of life for folks there without contributing to displacement. While the Luggage Store has been instrumental in helping to establish the careers of important artists like Alicia McCarthy, Xylor Jane, Chris Johanson, and Barry McGee, it’s also run the In The Streets festival and developed the area’s only green space, the wonderful guerilla park known as The Tenderloin National Forest. So I think you can have art without automatically displacing.

Streetopia took advantage of the city’s general focus on aiding artists in the Tenderloin by receiving permission to use a storefront in the Warfield building for the show. But rather than use it to make decorative art, we turned the storefront over to Julian Dash, an artist who has founded a grassroots DIY afterschool program for area youth in which Julian teaches kids how to refurbish old clothing and then sell the clothes for money they can keep. While Julian’s project was fun and worthwhile, it also drew attention to the fact that these storefronts have been deliberately speculated upon and left empty for decades by area landlords. In our Tenderloin utopia, the city would actually give resources to area kids to help devise their own economic uplift rather than give tax breaks to outsider corporations who have no intent on helping the community in any way.

Around the time that Streetopia was being planned, a real estate gold rush was on as arts groups like Burning Man rushed like Sooners to claim space for themselves along the city’s skid rows in transition. These groups seemed to take it for granted that their very presence was a positive change for the area and embraced official narratives about gentrification in which the displacement of longtime residents and the “improvement” of the area were conflated.

The attitude of Burning Man was emblematic. Burning Man’s director, when asked by the Chron if he was worried about moving to 6th Street, told the paper, “We build and tear down cities in the desert every year.” The group commissioned public sculptures of huge metal dandelions that they placed around Market Street which seemed to send a clear message to the community that Burning Man saw the area as an empty lot full of weeds that they could do anything they want with. (Ironically, the Kaplan’s army/navy supply store on Market Street, famed for supplying burners with their supplies for the playa, was an early casualty of the changes on Market as the two-story building was soon bought to be torn down to make way for a luxury apartment tower).

48H How did the book come together, and what was the impetus behind launching the book and a return series of events now? Can you share some of the highlights of the two events?

EL Well, one political aspect of Streetopia was that we were trying to make a social space where different communities could come together in real life and in real time to consider tactics to fight displacement. We felt like it was important that it be about the one-on-one in the moment and not be about documenting the show. Not to mention how gross it would be to, like, take pictures of people eating at the Free Cafe and use that as our “social practice” art!

This was a great strategy for making events that felt human and real but not such a good plan for making a book. The result, of course, was that when the show was over, I had almost no photos of anything that took place during it! But many people urged me to make a book. So I reached out to artists and audiences and the book ended up using crowd-sourced photos sent in by participants. I reached out to various folks to add essays to the book that would consider the show’s context in current art practice and within current social movements. Booklyn Press helped raise money for the show and book by selling limited edition arts books made with artists from the show. We sold 30 of these books to college libraries and institutions like Yale Library, UC Bancroft Library, MOMA, The Getty, Hammer Museum, etc.

I wanted the book to take a larger focus than just the Streetopia show itself. The book uses the show and the projects from Streetopia as a point of departure to consider the place such art holds in current international social movements, to consider the nature of gentrification today in this neoliberal era, to link what is happening in SF to the larger processes of urbanization across the globe, and to make a strong and clear case for the importance of utopian thinking in social movements.

I wanted the book to give the ideas from the show a longer lifespan and to hopefully inspire others to consider how much might be possible even in times when a community’s material resources and morale might seem low. I also think that the book challenges mainstream conceptions of gentrification as simply the inevitible result of the contact between artists and low income communities. I demonstrate in the book that SF’s gentrification is actually the end result of fifty years of very deliberate and openly planned public policy.

There are two events in SF this week. I don’t think anyone in SF really needs me to come back to town to talk to them about what gentrification is! So we wanted to make something more involving. The first event is a panel discussion where we will talk about the ideas of Streetopia and bring folks together to talk about the current moment. Anti-Eviction Mapping Project will present on their current work around organizing folks and around changing the narrative around displacement. The second is a big book release party that includes music, art, and performance from people like Brontez Purnell, Christine Shields, Daisy World, Daphne Gottlieb, Diamond Dave Whitaker, E. Conner, Elaine Kahn, Erick And Ivy, Felidae, Future Twin, James Tracy, Jimmy Broustis, Julian Dash, Lynn Breedlove, and many more.

48H What are some of the ideas or exhibits from 2012 that you feel are especially prescient or resonant with the direction SF had headed since then?

EL There are several but a couple come to mind really quickly. Author Sarah Schulman came to Streetopia to sit on a panel with young queer activists in SF who had been seeking ways to link the lost radical potential of queer identity to struggles around displacement and inequality. Groups like Homonomixxx and a new iteration of Act Up had been using old school Act Up tactics like Schulman once helped devise to shut down banks and to organize around the foreclosure issue.

I think that we are currently faced with a displacement crisis that is massive and nationwide but one that is largely disavowed by those in power in much the same way that the true extent of the AIDS crisis was once denied by government in the 80s and 90s. Very little research has been done to examine the public health effects upon communities that suffer displacement from gentrification. But a Center for Disease Control study in Oakland in 2013 that I cite in the book did conclude that displacement shortens human life spans.

I think Occupy has done quite a bit to change the conversation around inequality in this country. I am hoping that Streetopia can be part of changing the conversation around gentrification. I think it will take nothing short of an Act Up style movement to drag the true extant of this crisis out in the open and force society to look at what it is really doing to people.

Another project from the show that was particularly prescient was the work of Sarah Lewison in the show. Sarah did a project that took as its focus the lost network of communes in the Bay Area during the 70s. In particular, Sarah focused on the work of the Kaliflower Commune — a queer utopian group of artists that had been part of groups radical queer theater groups like the Cockettes and Angels of Light and had been hugely influenced by the Diggers and their concept of Free. Kaliflower produced a weekly newsletter that they delivered by hand to over 300 other communes in the Bay Area! The paper included a lot of intercommunal classified ads that were the basis of an extensive non-monetary economy. One commune might need some folks to come over and paint the house and could offer, say, 40 pounds of rice in exchange. It was a true “sharing economy” right?

Sarah made packets of current communal art and info that would be made in the gallery and then distributed by volunteers to addresses of former communes from the Kaliflower network. A letter included in the packets explained the communal history of the physical house and asked folks to consider whether they might like to participate in such a network today. For volunteers, it was a way to map in real life this lost network and to see what a neighborhood might feel like when there are several of these communes within a couple blocks — places that a communard knew they could go at any time to find friends, food, drugs, sex, whatever.

In the Haight, many of these enormous Victorians that once housed 25 or more hippie communards now house a single person or couple and their steps now have signs saying, “Don’t sit here!” etc. Lewison’s project came just as the so-called Sharing Economy was on the rise and marked a true gift economy of sharing an barter that once existed in the Bay that the tech people have tried to co-opt.

48H The big question is always not just “can art make a difference,” but, as the current neoliberal practice of art-washing shows, “can art make the right kind of difference.” What are some of your thoughts about the larger role of art in a a hyper-capitalist/post-civic marketplace like the current SF?

EL Yes, art can make the right difference! As you say, it depends on who its for and what it says. We see now a rise of Bay Area design firms that seek to tweak and modify the existing urban environment in all of these tiny ways while ultimately offering no changes to the existing power structure. Utopia is not a design solution! These design changes to bike lanes or public seating are today accompanied by anti-homeless legislation or gang injunctions or other uses of police force that limit the ways many in the existing community can participate in public space.

We see the return of amenities like benches to Market Street as we see the homeless population being forcibly cleared from the area. I think artists need to acknowledge that they don’t exist in a vacuum. They can choose to make projects that ease gentrification or place a decorative coloring on it. Or they can choose to reach out to communities threatened by displacement and see what kind of help they need getting their message out and how art can help facilitate projects that won’t lead to displacement. I think its really that simple.

48H What do you think the chances of something as ambitious as Streetopia happening now are?

EL I think Streetopia demonstrated actually how many of these projects could exist at any time. Like you don’t actually need to convince people to go downtown to illegally occupy a public square necessarily; you could just organize your neighbors into making a Free Cafe right now. Many of the events focused on grassroots groups like SF Coalition on Homelessness or SF Drug Users Union who were just regular folks who founded their own DIY organizations to affect public policy.

Streetopia was a tremendous amount of work but I think paradoxically it also demystified some of this stuff. Its all about bringing folks together to advocate for themselves right now. I would also say it was about having a ton of FUN! The show demonstrated to many of us involved how rewarding it felt to be working to make and live in the world we want to live in rather than complaining about the tech world we are always fighting. It was about being part of what we are FOR and not what we are against.

STREETOPIA: BOOK LAUNCH PANEL WITH ANTI-EVICTION MAPPING PROJECT

Thu/15, 7PM, free. Adobe Books, SF. More info here

STREETOPIA: BOOK LAUNCH PARTY

Fri/16, 7pm, free. Luggage Store Gallery, SF. More info here