By Zelda Bronstein

MAY 29, 2014 — At its May Day meeting, the San Francisco Planning Commission took a stand for blue-collar jobs, affordable housing, public transit, and government accountability: it refused to approve a staff recommendation to authorize the conversion of the industrially-zoned property at 660 Third Street into an office building.

Planning Department staff deemed the change a “routine” matter, so they placed the item on the commission’s consent calendar, meaning that they expected it to be passed without discussion.

Instead, the commission moved 660 Third Street onto its regular agenda and took public comment.

After hearing strenuous objections from representatives of the Council of Community Housing Organizations, Mission Economic Development Agency, Tenants and Owners Development Corporation, and the SoMa Leadership Council, among others, commissioners peppered staff and the applicant with pointed questions:

At a time when San Francisco manufacturing is undergoing a welcome revival, but manufacturers are leaving town because they can’t find space, why is the Planning Department asking us to shrink the city’s industrial building stock?

A sweeping plan to rezone Central SoMa is slowly making its way through the city bureaucracy and has yet to come before the Planning Commission. Why, then, are we now being asked to rezone the area parcel by parcel?

Did staff discount the development impact fees for changing 660 Third Street from industrial to office use and thereby encourage the elimination of industrial space and deprive the city of desperately needed funds for Muni and affordable housing? How are these fees calculated, anyway?

The staff report says 660 Third St. is currently occupied by office tenants; how can that be, when the owner is asking for permission to convert the property into offices?

In other words, has the building already been converted – illegally – and if so, why has nobody in the Planning Department done anything about it?

Failing to get satisfactory answers, the commission continued the matter to June 12, at which time staff are to fill in the blanks.

We can fill in a lot of them right now. And the information will say a lot of about the city’s ongoing failure to protect the industrial space that is under assault from an influx of higher-paying tech-office uses.

Rent: the essential factor

Industrial uses, known in San Francisco plannerese as production, distribution, and repair or PDR, need low rents. They cannot compete with high-rent uses, above all, offices. That’s always an issue in this town, which has the lowest percentage of industrially zoned land (6.8%) of any major city in the U.S. But with the tech-induced office boom, the scarce amount of industrial space is threatening the very survival of the city’s PDR economy.

Commercial rent control is banned by state law, so if a city wants industrial businesses and the middle-class employment they offer to people without higher degrees, as well as the essential services they provide to the city’s economic drivers—tourism, health, and tech—the best it can do is to zone for them.

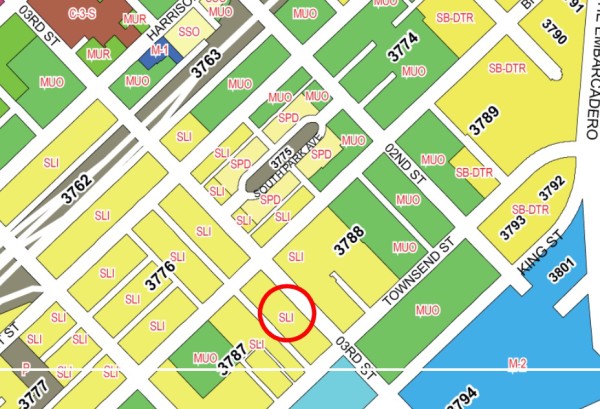

San Francisco has several zoning districts that protect PDR, all in the eastern part of the city. 660 Third Street sits in one: the Service/Light Industrial (SLI) Zoning District, part of the East SoMa Area Plan.

As defined by Sec. 817 of the city’s Zoning Code, SLI

is designed to protect and facilitate the expansion of existing general commercial, manufacturing, home and business service live/work use, arts uses, light industrial activities and small design professional office firms….General office uses…are not permitted.

Sounds good. But if a city is serious about protecting PDR, especially in a red-hot real estate market, it has to enforce its PDR zoning. Otherwise, owners of industrial property will charge rents that industrial users can’t pay, claim that they can’t find PDR tenants, and then lease the space to high-rent users. In today’s San Francisco, that means tech offices.

This is exactly what’s happening in the SLI and the other PDR-friendly zoning districts. Worse yet: when the Planning Department isn’t looking the other way, it’s expediting these unauthorized conversions.

Converted illegally?

Case in point: 660 Third Street. Situated about a half block above Townsend on the west side of Third, the property houses a four-story-plus-basement, red brick masonry, 88,000 square-foot building originally constructed as a warehouse around 1900.

660 Third Street is owned by Gorr Partners LLC, a real estate investment firm started in 1995 by the late Irving Rabin and now run by his family. Rabin, who died in 2012, also founded Rabin Worldwide, which he built into one of the largest industrial auction houses in the world. In 1970 he and his business partner Bernard Osher bought the San Francisco auction house Butterfield & Butterfield; in 1999 they sold it to eBay for $260 million.

During public comment at the Planning Commission, land use attorney Sue Hestor said that 660 Third Street had already “been converted illegally to office.”

Commissioner Gwyneth Borden subsequently asked the property’s owners about the property’s rental history.

The lawyer representing the Rabins, David Silverman, stated that the family had owned 660 Third Street since the 1970s, and that until six or seven years ago, the building had been an auction house.

“We’re not really allowing offices,” said Ariel Rabin, one of Irving Rabin’s sons. “We’ve always had people who are building things there….As a family, we’ve been offered ridiculous sums of money to convert it to fancy offices,” even as “we’ve always struggled to lease the property because PDR users have not stepped forward when we have vacant space.” In the mid-2000s, he said, the building sat vacant for five years.

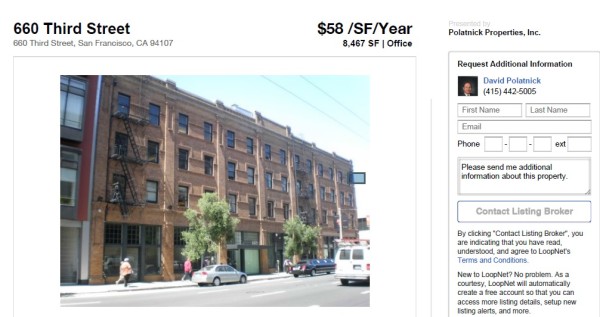

Regrettably, nobody on the commission asked Rabin about rents. As of May 14, an 11,864-square foot space on the 3rd floor of 660 Third St. was available for $51 a square foot per year, while a space on the first floor was going for $58. That’s what nice office space rents for — and it’s far more than any PDR business could afford.

According to the commercial real estate firm Kidder Mathews, in the first quarter of 2014 the average asking rental rate for industrial space in San Francisco was $11.39 a square foot, rising to $12.60 for high-quality space.

Rabin’s claim about not allowing offices was qualified by his attorney. “It’s a mix [of office and PDR],” said Silverman.

That’s not what Silverman said in the document he submitted to the Planning Commission on March 10, 2014. There he cited Section 101.1 of the city’s Planning Code, which establishes eight priority planning policies with which a permit must be consistent. One of those policies stipulates:

That a diverse economic base be maintained by protecting our industrial and service sectors from displacement due to commercial office development, and that future opportunities for resident employment and ownership in these sectors be enhanced.

Silverman commented: “No industrial or service businesses will be displaced by the Project.”

That claim seems to be borne out by tenant list posted in the lobby of 660 Third Street:

Of the seven businesses listed, none are conceivably engaged in production, distribution, or repair.

It might seem that two, Frog Design and Coalesse, fit the “small design professional office” category mentioned in the summary of SLI permitted uses. Frog describes itself as a “global product strategy design firm.” Coalesse’s website says the company is “a premium furnishings brand that delivers progressive live/work solutions.” How much either one, especially Coalesse, actually designs on-site is unclear. It’s also unclear whether Coalesse is open for business at 660 Third Street; its phone appears to have been disconnected, and the times I’ve gone by during the day, nobody’s home.

In any case, neither Frog Design nor Coalesse qualifies as a “small design professional office”—not because each is a far-flung international corporation, but because small design professional offices are permitted within the SLI Dstrict only when “the occupied floor area devoted to this use per building is limited to the third story or above”; and “the gross floor area devoted to it per building does not exceed 3,000 square feet per design professional establishment” (Planning Code Section 803.9(g).

Frog Design is on the 3rd floor of 660 Third Street, but according to the website of the commercial realty that manages the building, Polatnick Properties, the firm occupies 21,000 sf; and Coalesse is (or was) on the ground floor. In other words, they’re both, as planners say, noncompliant uses.

Using history

But there’s a way—a really complicated way—to legalize them and the building’s other office tenants: General office uses are allowed in SLI through a Conditional Use Authorization (CU) in Landmark Buildings or Contributory Buildings in a Historic District. (Planning Code Sections 187.48 and 803.9(a). And 660 Third Street is in a designated historic district, the South End Landmark District.

That’s why the planner assigned to 660 Third Street, Rich Sucré, is a historic preservation specialist, and why the project came to the Planning Commission via the Historic Preservation Commission.

As Sucré wrote in the draft resolution that he prepared for the Historic Preservation Commission’s February 19 meeting, in order for a project to qualify for the Conditional Use Authorization (which can only be made by the Planning Commission), first “it must be determined that allowing the [office] use will enhance the feasibility of preserving the landmark, significant, or contributory building.” In other words, the Historic Preservation Commission had to be persuaded that without the office rents, the owners could not afford to restore or preserve the structure.

The Historic Preservation Commission was apparently persuaded: Its members unanimously approved the resolution.

It’s reasonable to think that a significant factor in that approval was the testimony of the Rabins’ lawyer, Silverman, the only person to speak at public comment. Silverman told the commission: “the building’s vacant.”

That’s hard to believe. In the executive summary that he prepared for the Planning Commission’s March 27 meeting (the item was continued to April 3 and then to May 1), 660 Third Street, Sucré wrote, “is occupied by office tenants.” Did they all move in between February 19 and March 27?

They did not: calls to two tenants, Frog Design and Healthline, revealed that they’ve both been at the address for years, and a third longtime tenant is the commercial realty that manages the building, Polatnick Properties.

Strikingly, the memo that Sucré presented to the Historic Preservation Commission said nothing about the building’s past or current tenants or lack thereof. Nor did Sucré challenge Silverman’s assertion that the building was vacant. The commissioners, for their part, didn’t ask. But absent that information, as well as a pro forma laying out the project’s financials, how could it be determined that the conversion from PDR to office use was necessary to restore and maintain the building?

By contrast, the Planning Commissioners knew that the building had office tenants. They also knew that the Rabins had owned the building for a long time. With that knowledge in mind, Borden said, “I’m not clear why the change is necessary. It’s not a new owner in which the cost is high.”

Nobody—neither Rabin nor Silverman nor Sucré—explained why, without the office conversion, protecting the building’s historic character would be financially infeasible.

Contrary to Rabin’s statement that nothing has been changed at 660 Third Street, and consistent with Hestor’s allegation that the PDR-zoned building has been illegally converted into offices, abundant evidence indicates that the vintage warehouse was turned into a fancy office building nearly 20 years ago.

Since 1984, the the city’s Department of Building Inspection has issued 65 building permits for work at the property costing millions of dollars.

A few examples of the most expensive projects:

1986-7: new openings cut in the exterior brick walls, $725,000

1996: 4th floor improvements, $330,000

1996-2000: electrical work, $304,250

1997-2000: 1st floor improvements, $100,000

1997-2001: 2nd floor improvements, $315,000

2000: underpinning for new construction, $120,000

2007-8: new walls at 3rd and 4th floors, $812,000

2008: re-roofing, $175,200

2011: 3rd floor improvements, $200,000

For a decade, DBI waffled on its description of the building’s use. In 1984, it designated the place as 10-OFFICE, in 1985-1987 as 20-WAREHOUSE, NO FRNITUR, in 1988-9 as 15-RETAIL SALES (the auction house?), and in 1989-1990 as 05-FOOD/BEVERAGE HNDLING. Since 1994 the building use has been designated as 10-OFFICE.

By contrast, commercial real estate broker David Polatnick makes no bones about the conversion of 660 Third St. to offices in the mid-Nineties. Indeed, the Polatnick Properties website counts the project as one of his “success stories”:

660 THIRD STREET, SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

The Challenge

660 Third Street started as a brick and timber warehouse originally constructed in 1906.The Solution

David Polatnick advanced a strategy for repositioning the operation and tenancy of the building. In 1996, Polatnick put together a team to re-tenant the 85,000 square foot building. The building went through a complete renovation, which included seismic upgrade and code compliance for office, retail and tenant improvements.The Result

With an eye for the New Economy, Polatnick tripled the electrical power to the facility and installed fiber optics, the first commercial building in San Francisco to do so, making it into one of the most sought after multi-media addresses in multimedia gulch.

In June 1996 Gorr Partners leased 21,255 sf at 600 3rd St. to Wired Ventures for $18,155 a month. Wired used the place as its headquarters. Polatnick has not returned my repeated calls asking, among things, how long Wired stayed. My online research suggests that the company was there as late as 2005.

The current ads for the 8,467-square foot ground floor office and the 11,924-square foot 3rd floor office space both mention recent refurbishments. The ground floor unit is said to include a “Conference Room/’High-End Ping Pong Parlor.’”

Could 660 Third St. still be used for PDR?

Silverman’s March 10 submittal to the planning commission purports to offer further evidence of 660 Third St.’s post-industrial character: it claims that the building lacks the parking and loading capacities that PDR businesses need for their work:

Most of the nearby parking lots fill up in the morning and cannot take cars mid-day. San Francisco Giants’ games create additional parking issues….The Building’s full lot coverage precludes any off-street parking or loading, thereby eliminating many uses that would be principally permitted in this district.

Silverman’s list of those uses includes:

“Trade Shop – Precluded by lack of parking”; “Business goods and equipment repair service – Precluded by lack of parking and loading”; “Business services – Precluded by lack of parking and loading”; Light manufacturing – Precluded by column spaces, and lack of parking and loading.

At the planning commission’s meeting, Commissioner Michael Antonini, presumably echoing the attorney’s submittal, opined that the lack of parking and loading meant that “this location is not appropriate for core PDR.”

What nobody, incuding planning staff, noted is that 660 Third Street does have loading capacity. That’s clear from the floor plans, which show a loading dock and two freight elevators in the rear of the building, which is on quiet Ritch Street—perfect for truck deliveries and pickups.

Polatnick Properties’ website has an ad for 15,000 sf of storage space in the basement that’s accessible by “2 freight elevators and 1 dock high loading area.”

The realtor’s website also says that gated parking is available with office space #302. The parking lot is also accessed from Ritch.

It’s possible that Gorr Partners doesn’t own the lot but only leases it for tenants of 660 Third Street—something else I wanted to check with both Polatnick and Silverman. After I’d left several messages at Silverman’s law firm, Reuben, Junius & Rose, the attorney instructed the woman who answers the phone to tell me that “he has no comment.”

For now, it appears that, contrary to Silverman’s claims, as far as loading and parking is concerned, 660 Third Street could still support PDR.

As Commissioner Borden commented on the responses to her query about the building’s history: “this raises a lot of questions.”

Why is Planning abandoning PDR?

But the most serious question raised by 660 Third Street isn’t whether the Rabins and their attorney are fudging the truth about the building’s history and character; it’s why the Planning Department is urging the Planning Commission to convert a building from industrial to office, when the city’s official policy is to expand industrial space in San Francisco.

That policy was enunciated and affirmed at the Planning Commission’s March 13 meeting by Ken Rich, Director of Development in the Mayor’s Office of Economic and Workforce Development (OEWD).

Speaking in support of Supervisor Malia Cohen’s bill to encourage the creation of new PDR space on 16 parcels north of 20th Street, Rich said, “We are dealing with a pretty urgent need to provide more space for manufacturing in the city.” Mayor Lee, he noted, had come into office with a seventeen-point jobs plan whose Point 7 says: “Revive local manufacturing. Help it start, stay and grow here in San Francisco.”

The city’s policy of industrial expansion was also approvingly cited in the Planning Department’s executive summary of Cohen’s proposed legislation “PDR space is in high demand,” wrote planner Steve Wertheim,” vacancy is exceedingly low, and we are now seeing PDR companies leaving San Francisco because they cannot find place to expand.” The department urged approval of the bill, a recommendation that the commission followed.

But at the commission’s May 1 hearing 660 Third Street, nobody from either the Mayor’s Office or the Planning Department said a word about the city’s commitment to creating more PDR space. Rich, a former Planning Department staffer, attended the hearing but did not speak. Planning staff spoke but never mentioned the official pro-PDR position.

In fact, the Planning Department’s handling of 660 Third Street would lead you to think that the city has a policy of PDR endangerment, not protection.

Consider the two draft motions that Sucré, prepared for the planning commission’s approval. The first motion authorizes an allocation of 80,000 sf of office space at 660 Third Street, an action necessitated by Prop. M, the voter-approved cap on annual office development; the second authorizes the conversion of up to 80,000 sf of industrial space to office.

Both motions claim that the proposed project complies with all of the eight priority-planning policies with which, says Planning Code Section 101.1(b), a permit must be consistent, including the policy stipulating

That a diverse economic base be maintained by protecting our industrial and service sectors from displacement due to commercial office development, and that future opportunities for resident employment and ownership in these sectors be enhanced.

The Planning Department’s assessment, set forth in both draft motions:

The proposed project will assist in maintaining a diverse economic base by enhancing a commercial use.

Huh? The policy is all about protecting PDR from displacement by just the sort of commercial office development that the two motions would authorize at 660 Third Street. Sucré’s resolutions don’t mention the policies’ references to both the displacement and the protection of PDR.

The second draft motion, the one authorizing the conversion of up to 80,000 sf of industrial space to office use, cites and then eviscerates a second PDR-friendly official policy:

8. General Plan Compliance. The Project is, on balance, consistent with the following Objectives and Policies of the General Plan:

COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY

Objectives and Policies

OBJECTIVE 2:

MAINTAIN AND ENHANCE A SOUND AND DIVERSE ECONOMIC BASE AND FISCAL STRUCTURE FOR THE CITY.

Policy 2.1:

Seek to retain existing commercial and industrial activity and to attract new such activity to the City.

Once more, the industrial retention and attraction element of the policy is missing. But this time, we’re treated to some additional mind-bending logic.

“The Project will enhance an existing use and will enhance the diverse economic base of the City.”

True, the project will enhance an existing use. That use, which is unspecified, is office. It stands to reason (this is the one logical thing here) that the Planning Department wouldn’t say that the existing use is office, because the point of the motion is to authorize a change from PDR to office, not to enhance an existing office use.

Compare the contorted treatment of PDR protection with the planners’ straightforward nod to the creation of new tech office space. In accordance with Planning Code Section 321 which establishes standards for San Francisco’s Office Development Annual Limit, the project, says the first draft motion, will meet the “Needs of Existing Businesses” by “provid[ing] office space with high ceilings and large floor plates, which are characteristics desired by emerging technology businesses.”

What’s the point of a planning process?

At the May 1 hearing, Planning Director John Rahaim dispensed with subtleties when it became apparent that the commission was not going to rubber-stamp his department’s recommendations: Antonini’s motion to approve the allocation of new office square footage and the conversion from industrial to office had failed for lack of a second, and commissioners had begun to talk about ensuring no net loss of industrial space and requiring some percentage of PDR at 660 Third Street.

Rahaim jumped in: “Our experience,” he said, “is that contemporary PDR uses don’t go into upper floors any more. They want to go onto the ground floor.”

Not according to SFMade Executive Director Kate Sofis. At the Planning Commission’s March 13 hearing on Cohen’s PDR bill, Sofis, who played a major role in drafting the legislation, offered two local examples of the building type that would be a good fit for the proposed Small Enterprise Workspaces (SEWs): TechShop and ActivSpace—both multi-story buildings.

“TechShop,” Sofis said, “ is ‘three stories of machines and equipment. We have seen many SFMade companies incubate themselves at facilities like TechShop, which is technically an industrial facility.”

Like the expurgation of the city’s industrial protection policies from the Planning Code, Rahaim’s swipe at PDR only hints at the Planning Department’s aversion to retaining, much less expanding, industrial space South of Market. For a full-blown expression of that aversion, you have to go to the Central SoMa Plan.

The plan’s authors openly concede that their proposal, now in draft form, would eliminate at least 1,800 PDR jobs by replacing most of the SLI and Service/Arts/Light Industry (SALI) zoning in the plan area with Mixed-Use Office (MUO) rules.

Seeking to protect PDR, SLI allows prohibits general office and hotels; SALI prohibits offices, hotels and residential uses. MUO allows everything but adult entertainment and heavy industrial uses. No way will PDR survive under MUO.

In another arbitrary gesture, Sucré cites the Central SoMa Plan as grounds for authorizing the conversion of 660 Third Street into offices, even though the plan is not expected to become law until 2015 at the earliest.

As Borden commented at the May 1 hearing: “What’s the point of a zoning process if everybody changes all the uses before the process?”

Is anybody at Planning even watching?

The Central SoMa Plan makes explicit the Planning Department’s longtime semi-clandestine, anti-PDR, pro-office manipulation of city law and policy—a manipulation that’s implicit in its decades-long toleration of illict activity at 660 Third Street and its current efforts to legalize that activity ex post facto.

How does the department justify this behavior?

My Kafkaesque email exchange with Planning Department Communications Manager Gina Simi suggests that the planners doesn’t bother with justification, because they don’t admit that anything’s wrong.

I contacted Simi after Department of Building Inspection Communications Director Bill Strawn told me that “the routing on any permit,” as recorded on the DBI website, shows “the date when DBI sent it along to Planning, and the date when Planning sends it back to DBI, over to Fire, etc.” I’d also been told by Strawn’s colleague Ed Sweeney, Deputy Director of Permit Services, that “Planning has reviewed [660 Third Street] many times.”

If Planning had reviewed and approved all those permits, how had its staff failed to notice that the building had been renovated for high-end offices? As I wrote in a May 9 email to DBI that I cc’d to Simi:

Ed Sweeney’s reply below suggests that the planning department would have been aware of this de facto conversion, but the [current] request for a change of use indicates that it was not. Indeed, Sweeney’s reply suggests that planning has expedited an unauthorized conversion of an industrial building to an office use. It also suggests that planning has the last say in these matters. Is that true?

On May 12 Simi emailed back:

DBI maintains all records of building permit information; we do not track DBI’s authorization of permits for work on property. We review building permits once DBI refers them to us….

A change in the DBI occupancy is not a change in use according to the Planning Department. DBI’s codes are not our codes.

I do not see anything in Mr. Sweeny’s [sic] reply below that suggests that we expedited an unauthorized conversion of any kind; this is not the case and this is the first I or anyone in the Department has heard such a suggestion. We were not aware of the conversion until the filing of the present application.

They “were not aware of the conversion” until now? How was that possible?

In reply, I emailed Simi: If DBI and Planning have different standards for assessing changes in use, what are they? If Planning doesn’t track DBI’s authorization of permits for work on property but does review such authorization, what exactly goes into such a review?

Her response:

DBI determines the appropriate review for a specific permit based upon the work submitted by a project sponsor, and DBI determines whether additional review is required by Planning or any other City agency.

Building Occupancy Codes do not correlate to Use Clarrifications in the Planning Code, and Building Occupancy is not Use Classification. Change of Use is when you move from one land use category to another in the planning code—and the process depends on the zoning district.

I hope that helps.

I emailed back: “I’m afraid it doesn’t.” She still hadn’t answered my question: how does Planning determine whether a property has undergone a change of use? So I tried again.

“Without dealing specifically with 660 Third St.,” I wrote,

exactly what criteria does Planning use to determine whether a property classified as an industrial building (by Planning) in the SLI zoning district in the East SoMa has been converted to office use. Clearly, it’s not the character of the tenants. What is it, then? And are the criteria specified in the zoning code or elsewhere? If so, please tell me where I can view them.

A week later (May 22), Simi hadn’t replied, so I turned to the city’s Zoning Administrator, Scott Sanchez. What, I asked, are the criteria that Planning uses to determine if a property in the SLI zone has undergone a change of use from industrial to office? Could you please direct me to the place in the zoning code where those criteria are set forth?

Sanchez’s reply was prompt, succinct, and disquieting:

While the Planning Code contains definitions of uses, it does not establish criteria or procedures for determining if a property has undergone a change of use from industrial to office. Such determinations are typically based on research, which may include: permit history, assessor’s records, reverse phone directories, lease information, Sanborn maps, historic photographs, historic resource evaluations and any other form of documentation that provides evidence of current and/or past uses [emphasis added].

Along the same lines, Sanchez also told me that

[t]he Planning Code does not provide procedures or criteria for determining whether a CU is financially necessary for restoring or maintaining a historic building (beyond what is in Section 803.9). We rely on the expertise of our historic preservation staff and the Historic Preservation Commission to review these proposals and advise [emphasis added].

At a meeting of the Eastern Neighborhoods Citizens Advisory Committee last February, CCHO co-director Fernando Martí asked how the city was going to enforce the zoning in Cohen’s PDR Facilitation bill and ensure that the new space authorized by the law would be occupied by industrial businesses, not tech offices.

Planner Mat Snyder responded: “I don’t know if we have a precedent. Most enforcement is complaint-based.”

Now it turns out that when it comes to monitoring the illicit conversion of industrial space into offices, there aren’t any rules to enforce; staff are pretty much free to make it up as they go along (this is planning?). Combined with the planners’ evident disdain for PDR, that license goes a long way toward explaining the debacle at 660 Third Street.

It’s happening all over

And 660 Third Street is no aberration. At the Historic Preservation Commission’s February 19 meeting, Commissioner Jonathan Pearlman voiced concern over the huge amount of PDR space that the commission’s actions had recently opened up to office conversion.

Besides the 80,000 sf at 660 Third, Pearlman cited the five-story, 1916 concrete warehouse building at 665 3rd, right across the street from 660 Third, whose owners are seeking a change of use in up to approximately 123,700 sf of offices. Last September the commission found that the proposed project—the conversion into office use—would enhance the financial feasibility of preserving the building’s historic character. Like 660 Third, the place is already tenanted by office users. On October 24 the Planning Commission approved the property’s conversion.

Pearlman also cited the 330,000-square-foot structure at 2 Henry Adams, known as the Showplace, an anchor of the city’s design district. In March the Historic Preservation Commission granted the building landmark status. The owners have applied for a change of use from PDR—designer showrooms fall into the “D” for Distribution category—to office. The proposed change has sparked fear about the displacement of the tenants and the dispersion of the city’s design sector.

The 2 Henry Adams case has yet to come before the Planning Commission. If it’s approved for conversion, the city will have formally handed over a total of 533,700 sf of PDR to new office space—most likely tech office space. And that’s not counting the many earlier official conversions or existing illicit makeovers (for a particularly flagrant, recent example, see 340 Bryant).

Acknowledging that commercial gentrification is ultimately an issue for the Planning Commission, Pearlman asked, “Why aren’t we questioning that all this PDR is disappearing from the ranks?”

Commission Chair Karl Hasz followed up with a different query. Stating that “PDR is more viable in the smaller buildings” and “on a smaller scale,” he wondered, how are you ever going to fill [big chunks of square footage like this] with PDR?”

Planning Director Rahaim chimed in: “It’s particularly tough to fill it on the upper floors,” a comment that foreshadowed the opinion he offered at the Planning Commission’s May 1 meeting.

Like the claim that PDR can only go on first and second floors, the notion that finding tenants for big industrial buildings is a tough sell flies in the face of current reality. The Planning Department’s dossier on 2 Henry Adams contains no evidence that the owners are having a hard time finding PDR tenants or that financial considerations necessitate the conversion to office use.

If anything, the challenge is for San Francisco’s successful industrial businesses to find enough local space to accommodate their expansion. Witness the recent much-publicized, much-lamented move of premium chocolatier Tcho from its 29,000-square-foot space on Pier 17 to a 49,000-square-foot space in west Berkeley. The company wanted to stay in San Francisco but couldn’t couldn’t find a big enough facility. SFMade’s “2013 State of Local Manufacturing Report” estimates that the city’s “manufacturing and allied design/engineering sectors” need “(conservatively) 300,000 – 500,000 sf a year of new industrial space.”

Even the new PDR space authorized by Cohen’s PDR Facilitation legislation is vulnerable to the tech office incursion—legally so, no less. The new law opens up PDR-zoned land to office development in the hope that the latter will subsidize the creation of industrial space.

Unfortunately, Cohen refused to put a cap on office use in SEW projects. Worryingly, as of early May, only two of the 44 tenants at ActivSpace in the Mission, hailed by the supervisor and SFMade as a prototype for the SEW format, were engaged in PDR. Given the huge gap between industrial and office rents, as well as the Planning Department’s desultory attitude toward industrial displacement, what’s to keep landlords from renting their entire property to office users?

With that question in mind, Supervisor David Campos planned to introduce an amendment to Cohen’s bill that would require at least 50% PDR space in a SEW facility. He dropped that plan, he told me, after it became apparent that most of his fellow supervisors, their professed enthusiasm for PDR notwithstanding, would not support the modification. But Campos told me that he has not dropped his “concern that much more space would go to offices than PDR” in SEW projects, adding that he “would monitor the situation and if necessary, step in.”

The other format authorized by Cohen’s bill, Integrated PDR, does cap office, but at 2/3 of the total square footage. Again, why would landlords bother renting to any PDR at all?

After intense lobbying by CCHO, MEDA and the SoMa Leadership Council, Cohen agreed to make IPDR and SEW a three-year pilot project.

At the May 1 meeting, planning commissioners talked about using IPDR as a model for 660 Third Street. The commission should bear in mind that it remains to be seen whether the new format will foster new PDR space, and if it does, how much and under what conditions.

And if the lesson of 660 Third Street applies, what really needs to change is not the city’s zoning code but the cavalier attitude of the people who administer it.

Next: Is the city allowing building owners to cheat Muni and affordable housing by discounting the fees they have to pay to convert PDR space into offices?