Critical funding, equity issues playing out with very little public input

By Zelda Bronstein

SEPTEMBER 1, 2015 — Last week the power struggle between the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and the Association of Bay Area Governments intensified, as the Sierra Club and the Six Wins for Equity Network entered the fray. Meanwhile, the agencies’ joint ad hoc committee resumed its secret deliberations on consolidating the planning functions of the two agencies.

Routinely ignored by the media, MTC and ABAG operate in obscurity at their MetroCenter headquarters in Oakland. That’s unfortunate, given their huge impact on where Bay Area residents live and work (or not), and how we get around. MTC oversees the region’s transportation planning; ABAG manages its planning for land use and housing. Together they prepared the region’s first, state-mandated Sustainable Communities Strategy, Plan Bay Area 2040, approved in July 2013. Under the aegis of that “blueprint,” as they call it, the two groups expect to hand out $292 billion in public funds.

Their current dispute involves money. Finance-wise, the two partners are highly unequal. MTC has an annual budget of more than $900 million; ABAG’s budget is $23.6 million. More to the point, ABAG depends on MTC for crucial funding. The first public sign of trouble appeared in late June, when MTC voted to fund ABAG’s planning and research staff for only six months ($1.9 million) instead of the customary full fiscal year.

The timing of the MTC vote was not coincidental. At the end of December the two agencies are scheduled to move into their plush new headquarters in San Francisco. If major administrative changes are in the offing, MTC officials want to make them before the relocation.

But what’s really at stake is not efficiency; it’s who will call the shots, and in what direction they will aim. In particular, will social justice count in Plan Bay Area 2.0?

The social justice question provided the subtext of the contentious July 10 joint meeting of the MTC Planning Committee and the ABAG Administrative Committee. The agenda carried dueling recommendations from MTC and ABAG staffs over whether a key anti-displacement policy that appears in the first iteration of Plan Bay Area should appear in the blueprint’s 2017 update, which is now under way.

The contested policy, which constitutes one of the “performance targets” in the current plan, reads as follows:

House 100% of the region’s projected growth by income level (very-low, low, moderate, above-moderate) without displacing current low-income residents.

ABAG staff wanted to keep the policy; MTC staff proposed to replace it with this:

House 100% of the region’s projected growth by income level with no increase in in-commuters over the Plan baseline year.

The disagreement stems from the agencies’ dispute over how to respond to the Building Industry Association’s August 2013 lawsuit over the omission of in-commuters—people who drive into the Bay Area to work—from the calculation of the region’s population. The out-of-court settlement stipulated that in-commuters would be included in the next edition of Plan Bay Area. It said nothing about removing the anti-displacement policy.

Unsurprisingly, BIA supports MTC’s proposal. So does the Bay Area Council, the lobby shop for big business in the region. The Six Wins for Social Equity Network, which campaigned to have anti-displacement language included in Plan Bay Area 2013, opposes its deletion.

At the July 10 meeting, a heated debate failed to resolve the issue. Staff members were directed to return in September with further analysis and recommendations.

Relations between the two agencies worsened during the July 16 meeting of the ABAG Executive Board. There ABAG President Julie Pierce, a member of the Clayton City Council, revealed that for three months a small, secret ad hoc committee of MTC and ABAG officials had been trying to resolve the differences between the two agencies. She and ABAG Executive Director Ezra Rapport put out a memo accusing MTC of effectively seeking to take over ABAG.

In response, MTC Chair Dave Cortese distributed his own memo accusing Pierce and Rapport of having broken faith with the ad hoc process, and stating that he would now consult only MTC Executive Director Steve Heminger about the prospect of a consolidation or merger.

At the August 5 meeting of ABAG’s Regional Policy Committee, Pierce said that the ad hoc committee had reconvened, and that she’d asked ABAG staff to analyze the options that Cortese had laid out. She also staved off collective action. “It’s not time to call out the troops yet,” said Pierce. “Let us do the work, and we’ll come back to you in September.”

Community activists have long complained that ABAG and MTC are undemocratic institutions that give citizen input short shrift. That charge is accurate. What the current power struggle reveals is that ABAG’s own internal processes are undemocratic. With the agency’s independence, not to say its survival, at stake, its president secretly convenes an ad hoc committee that meets behind closed doors and then squelches input from the rest of the agency’s voting officials. Worse yet, with one exception, those officials don’t seem to care.

The only member of both the ABAG Executive Board and Administrative Committee, which is authorized to act when the Executive Board can’t, to call for greater accountability from Pierce and for collective initiative has been Novato Mayor Pro Tem Pat Eklund.

At the July 16 meeting, Eklund asked Pierce to name the members of the ad hoc committee. Pierce did so: besides herself and Cortese, the committee comprises Alameda County Supervisor Scott Haggerty, Solano County Supervisor Jim Spering, and Napa County Supervisor Mark Luce.

Eklund also proposed convening the ABAG General Assembly, which includes a representative of every city and county in the region, so that the tensions between the two agencies could be openly and broadly vetted. (MTC lacks both an equivalent general body and any city representation at all.) And she suggested that ABAG ask state legislators to create an independent funding source for the agency. Nobody picked up on those ideas.

On August 5, after Pierce mentioned that she’d “added issues” to the ad hoc committee’s agenda, Eklund asked for specifics. Pierce declined to give them, stating that she would write a memo in the future.

On August 13, Executive Board members received an emailed memo from Pierce. On the same day Cortese released another memo of his own. Both addressed the “MTC/ABAG relationship.” Pierce wrote that her statement had been issued “as an addendum to MTC Chair Cortese’s July 16, 2015 and August 13 memos.”

Neither document mentions Cortese’s July 16 decision to abandon the ad hoc committee. Nor do they allude to the fight over keeping anti-displacement language in Plan Bay Area. As the two executives have it, the problems between MTC and ABAG are strictly administrative and financial. Moreover, consolidation of the agencies’ planning functions seems to be a foregone conclusion; all that remain to be worked out are (admittedly major) technical details.

Thus Cortese, purporting to “provid[e] clarity and transparency,” offered the following list:

- The work product of a consolidated planning department would continue to be approved by the joint Planning/ABAG Administrative committees and the MTC commission and ABAG executive board;

- The existing statutory authority of the MTC commission and ABAG executive board would be respected and maintained;

- A consolidated planning department would offer various benefits. These include using taxpayer dollars more efficiently by speeding up internal processes and improving the quality of external communications, and better communication with cities and counties.

Then came the ritual nod to local control, meaning the control of city and county governments, not the electorate:

A consolidated staff function would not diminish local governing authority—indeed the statutory mandate for local control would be maintained; and

4. The proposal for a consolidated planning department will include a retention policy that would require MTC to offer employment opportunities to all ABAG Planning and Research staff at commensurate salaries and benefits.

Cortese didn’t note that, unlike MTC employees, ABAG staff members are unionized. In the event of consolidation, how would that difference be resolved?

Pierce’s memo of August 13 first offered a sanitized history of the consolidation debate, mentioning neither the impending move to San Francisco nor the disagreement over anti-displacement policy in Plan Bay Area, and then briefly reviewed “key issues.” Here are the highlights.

- Programmatic issues

Noting that “ABAG planners do much more than work on Plan Bay Area,” Pierce listed their other assignments, such as assisting local staff and elected officials and studying economic development and regional issues. “How,” she asked, “would the current range of staffing and technical support functions continue under consolidation”?

- Governance and local input

“It is unclear,” Pierce wrote,

how staff appointed and paid by MTC, particularly the planning director, would continue to be responsive to ABAG—which would no longer have budget or line authority over them. This arrangement could create obstacles to ensuring the level of engagement and input required to produce a robust SCS [Sustainable Communities Strategy] or RHNA [Regional Housing Needs Allocation] that has the support of the ABAG Executive Board, which would ultimately remain responsible for adopting both but no longer have a direct relationship with staff.

How, then, would a consolidated planning department “maintain the existing level of local contact and input”? And “how would ABAG’s authority over land use issues outlined in SB 375”—the 2008 state law that mandates the creation of a Sustainable Community Strategy for each region—“and MTC’s authority over transportation issues in the SCS and the RTP [Regional Transportation Plan, which is part of the Plan Bay Area] be structured?”

- Financial impacts

In the past five years ABAG has secured more than $50 million of grant money to support regional planning, including Plan Bay Area. “How would ABAG’s ability to continue its critical grant-supported work be impacted by this consolidation?”

“Will ABAG’s reduced budget, authority and staff be sufficient to sustain the current level of [city and county] membership, which provides $2 million in dues—and support ABAG’s reaining Council of Government activities?”

Pierce also brought up the unionization issue. “ABAG planners,” she observed,

are part of SEIU and under a collective bargaining agreement, while MTC staff is not….How would the collective bargaining rights of ABAG planners be maintained by MTC under a consolidated department?

Pierce said the staffs of the two agencies would be making “informed recommendations” to the ad hoc committee in early September. Beginning in September, she and Cortese will be providing regular updates to their respective boards.

In conclusion, she reiterated her “let us do the work” approach:

I look forward to working with the ad hoc group and our colleagues at MTC. If you have questions or suggestions, please address them to both Chair Cortese and myself.

Pierce and Cortese elided the really tough questions: What about the goals of Plan Bay Area 2.0—in particular, fighting displacement of the region’s most vulnerable residents? And should the consolidation of MTC’s and ABAG’s planning staffs be on the table in the first place?

Last week the first question was raised by the Six Wins for Equity Network, and both were raised by the Sierra Club.

Six Wins, in its own words, “is dedicated to building the power, voice, and influence of low-income and working families and communities of color in fields of climate and environmental justice in the Bay Area.” The coalition takes its name from its six areas of concern:

- community power

- investment without displacement

- affordable housing

- robust and affordable local transit service

- healthy and safe communities

- quality jobs

The equity coalition means business. In 2013 it formulated the Equity, Environment and Jobs Scenario, a comprehensive, in-depth alternative to the Sustainable Communities Strategy that had been drafted by MTC and ABAG staff. The agencies’ own analysis found that when it came to the environment, health, and budget, the Six Wins plan bested the official draft, as well as other alternatives. In spite of that assessment, the official proposal was adopted, albeit with the anti-displacement language advocated by the equity advocates.

Six Wins is taking a similarly intense approach to the Plan Bay Area update. On August 18 the coalition sent MTC and ABAG a letter arguing that Plan Bay Area’s performance goals need to be strengthened, “not water[ed] down.” The letter emphasizes “the importance of maintaining a goal of zero displacement and of adding a new goal and performance measures related to the creation of quality jobs and economic inclusion” [emphasis in original].

So, for example, Six Wins recommends that all of Plan Bay Area’s “relevant targets” should be evaluated according to how they affect people with different incomes. If commute times are shrinking, does that shrinkage reflect the travel of all commuters or just the affluent ones?

Noting that “[t]he new Plan Bay Area, like the current one, will be in effect for only four years,” the equity coalition asked MTC and ABAG to take into account proximate outcomes, not just “hypothetical impacts thirty years in[to] the future.”

These recommendations are elaborated in a substantial attachment to the letter. Among other things, Six Wins suggests revisions to the draft Economic Vitality target. It now reads:

Increase the share of jobs accessible within 30 minutes by auto or within 45 minutes by transit by [TBD]% in congested conditions.

The equity advocates’ revised version:

Increase the share of income-matched jobs accessible within 30 minutes by auto and within 45 minutes by transit by X%.

“Income-matching” is a new concept to me. The letter says it means that the target should measure access between jobs and housing only if a given job pays a wage adequate to afford a given housing unit. To flesh out that meaning, we are advised to consult the Jobs-Housing Fit Ratio map on UC Davis’s Regional Opportunity Index .

As for the difference between “and” and “or”: “By allowing an increase in the share of jobs accessible within 30 minutes by auto or 45 minutes by transit,” says Six Wins, as in the current Economic Vitality target,

a scenario could reduce auto commutes to 30 minutes but do nothing to improve transit commutes. The goal should be to reduce transit commutes in order to increase ridership and decrease greenhouse gas emissions.

The equity coalition also wants to add an Economic Opportunity target:

Incease the proportion of jobs in the Bay Area that are living- or middle-wage (i.e., within a range such as $15 to $40 an hour, or as appropriate by subregion) by X percentage points, including in Priority Development Areas and Transit Priority Areas [places that local officials have designated for dense new construction].

Another Six Wins recommendation revises the draft target for Equitable Access. It now reads:

Increase the share of affordable housing in PDAs [Priority Development Areas] by [TBD]%.

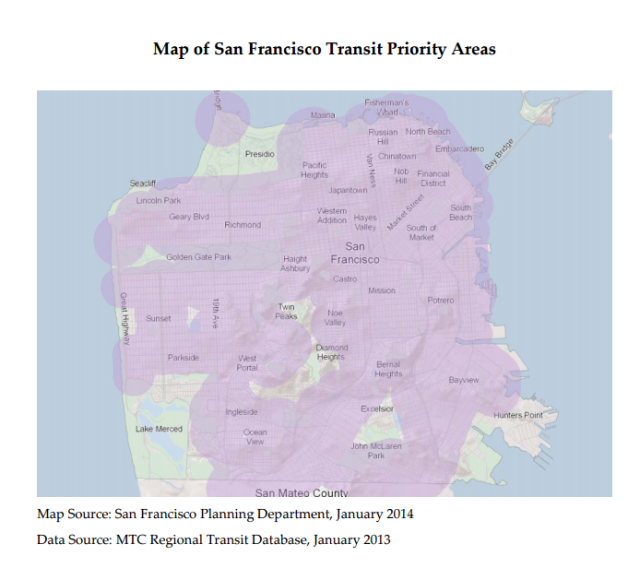

All of eastern San Francisco, plus Balboa Park, the Market-Octavia area, the 19th Avenue corridor and the Geary corridor out to Masonic, are PDAs. For useful “interactive” maps and details about PDAs throughout the region, see the Priority Development Area Showcase.

Arguing that it’s “just as critical” to locate affordable housing and to prevent displacement in “transit-rich areas of opportunity” as in PDAs, Six Wins amended the draft language to read:

Increase the net share of housing that is affordable to and occupied by low-income households in PDAs, and high-opportunity Transit Priority Project areas by X%.

Translation of the plannerese:

Transit Priority Projects—more accurately, Transit Priority Areas (TPAs)—are officially defined as places within a ½ mile of a major transit stop or “high-quality transit corridor,” meaning one with 15-minute frequencies during peak commute hours by 2035, and that contain at least 50% residential use and a minimum net density of 20 dwellings per acre.

“High-opportunity areas” are places that score highly in a composite score of 18 indicators developed by the Kirwan Institute of Race and Ethnicity (referenced by Six Wins) and that pertain to education, economic mobility, and neighborhood and housing quality.

Transit Priority Areas cover an even larger portion of San Francisco than Priority Development Areas, overlapping with the latter.

Six Wins modified “share of housing” with “net” to ensure that “if more existing affordable units are lost (e.g. through condo conversions, demolitions, removal of rent control provisions, or increasing rents that effectively price out residents than new units [are] built,” the measure should reflect that overall loss.

The Six Wins letter was signed by representatives of 33 organizations. The coalition casts an impressively wide net, as indicated by even a partial list of the letter’s signatories: AFSCME Council 57, Asian Pacific Environmental Network, Causa Justa, the Contra Costa Central Labor Council, the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy, East Bay Housing Organizations, Greenbelt Alliance, the Housing Leadership Council of San Mateo County, the North Bay Labor Council, Policy Link, Public Advocates, the San Mateo County Central Labor Council, the San Mateo County Union Community Alliance, the SF Bay Area Labor Council, the SF Council of Community Housing Organizations, TransForm, Urban Habitat, and Working Partnerships USA.

On August 21 the chairs of the Sierra Club’s three Bay Area chapters—Loma Prieta, Redwood and San Francisco Bay—sent MTC a short, pointed statement of support for ABAG. They encouraged MTC to “abandon [its] disruptive effort” to significantly “change its relationship with ABAG” and instead to “provide adequate funding” to its partner agency “for the customary period.”

That advice was accompanied by a reminder that the club and Communities for a Better Environment had entered into a settlement agreement with MTC and ABAG “over legal issues pertaining to Plan Bay Area,” and that the agreement involves “quite a bit of work to be accomplished in the near future.” For example, the “performance” of each Priority Development Area is to be extensively analyzed, well before the final approval of the region’s updated Sustainable Communities Strategy in 2017.

“Going beyond our settlement agreement,” the chairs wrote, “we think the expertise of ABAG and its relationships with local municipalties are [sic] needed as the 2017 Plan Bay Area is prepared.” They also commended the agency’s experience in dealing with “risks from sea level rise and seismic dangers in PDAs.” Lastly, they flagged the anti-displacement debate, averring that “ABAG can also be instrumental in addressing the huge and troublesome problem affecting the Sustainable Communities Strategy—displacement of low income residents from PDAs.”

The agenda for the September 1 meeting of the Regional Advisory Working Group includes revised staff recommendations for Plan Bay Area 2040’s goals and targets. The RAWG comprises representatives of local governments and county Congestion Management Agencies, as well as anyone with an interest in Plan Bay Area. It is jointly staffed by MTC and ABAG.

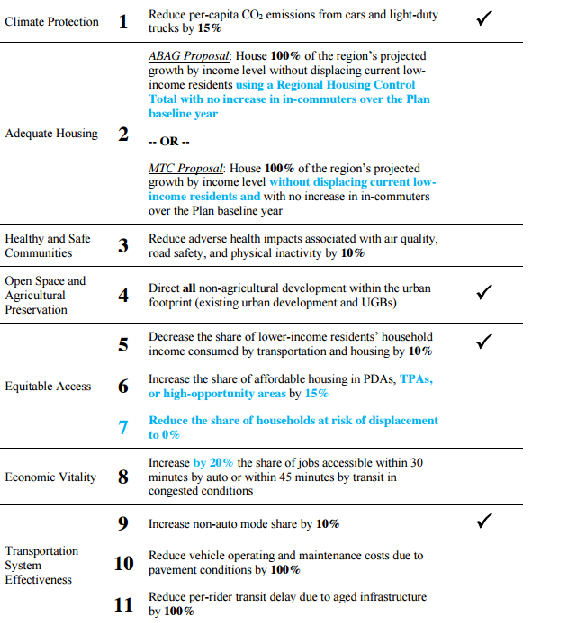

As this chart shows, the MTC proposal for the Adequate Housing goal now incorporates the disputed anti-displacement language. From the other side, the ABAG proposal now incorporates the reference to “no increase in in-commuters.”

The language of the two recommendations still doesn’t quite jibe, but the meaning is essentially the same. The Regional Housing Control Total is the 2010-2040 housing forecast for the Bay Area, including in-commuters. ABAG Planning Director Miriam Chion told me that ABAG wants to include “Regional Housing Control Total” to make explicit that the number in question relates to the terms of the settlement of the Building Industry Association’s lawsuit (the phrase appears there), and not the housing forecast alone.

The revised Equitable Housing goals also reflect the influence of the Sierra Club and Six Wins. The new language in Proposed Target 6—“TPAs, or high-opportunity areas”—and the whole of proposed Target 7—“Reduce the share of households at risk of displacement to 0%”—come straight out of the equity coalition’s August 18 letter. The staff memo notes without apology that “zero risk of displacement” over the time frame of the Plan (through 2040) is an “extremely aggressive” target.

At the MTC June 24 meeting where the vote was taken to fund ABAG planning staff for only six months, Commissioner and Solano County Supervisor Jim Spering spoke of “direct conflict” between the two staffs that had left MTC employees “demoralized”—a condition, he suggested, that would be solved by integrating the agencies’ planning departments. The revised recommendations for Plan Bay Area’s key goals indicate that the staffs of the two regional agencies are quite able to collaborate, and in a timely manner at that. So where’s the conflict?

Next steps for Plan Bay Area’s goals and targets:

September 1: Regional Advisory Working Group (information)

September 9: Policy Advisory Council (information)

September 11: MTC Planning and ABAG Administrative Committees (action)

September 17: ABAG Executive Board (final approval)

September 23: Metropolitan Transportation Commission (final approval)

In September the consolidation issue will also be on the agenda.

As the old saying goes, he who pays the piper calls the tune. If ABAG’s planning staff is folded into MTC, MTC will surely dominate. Given MTC’s rapport with the real estate industry, that bodes poorly for democratic transportation and land use policymaking in the Bay Area.

But even if ABAG keeps its planning staff and, better yet, gets the state legislature to provide it with an independent source of funding, regional policymaking in the Bay Area will have big problems.

Their genuine solicitude for the region’s disadvantaged residents notwithstanding, ABAG staff enjoy their own rapport with the real estate industry. That bond is rooted in planners’ fundamental commitment to growth. I refer in the first place to smart growth.

Smart growth—above all, its provisions for dense transit-oriented development (TOD)—is embedded in California state law, most notably SB 375 and in its progeny, SB 226 (2011) and SB 743 (2013). In the name of smart growth, these laws have weakened the California Environmental Quality Act, exempting many dense, transit-accessible developments from environmental review and thus from litigation. Plan Bay Area’s Priority Development Areas and Transit Priority Areas are predicated on those exemptions, euphemistically dubbed CEQA “streamlining” or “reform.”

But planners’ devotion to growth goes way beyond TOD. As the first edition of Plan Bay Area amply demonstrates, that commitment extends to population and jobs. Growth per se is good.

Leave aside aside the blatant contradiction between the faith in Growth and the possibility of saving what’s left of humanity’s fragile ecological niche. Bracket, too, for the moment, more modest questions: How are cash-strapped municipalities are supposed to pay for the services that will be needed to accommodate the immense increases in population and housing that Plan Bay Area envisions? And how can planning that extols Growth in the face of sea level rise and chronic drought be “smart”?

For the moment, consider only how the faith in Growth precludes a coherent position on equity and displacement in the Bay Area.

The RAWG’s September 1 agenda includes a substantial memo entitled “Understanding Displacement in the Bay Area—Definition, Measures and Policy Approaches.” Written by Chion and MTC Planning Director Ken Kirkey (more successful MTC and ABAG staff collaboration), the memo says that

[i]n the Bay Area, high displacement pressures are primarily caused by a combination of robust economic growth and lack of sufficient affordable housing for low- and moderate-income households. Other large metropolitan regions in the nation with a strong jobs market have also experienced similar pressures but not nearly at the scale and severity as in the Bay Area [emphasis in the original].

Regrettably, the authors did not ask why displacement is so much worse in the Bay Area than in other strong jobs markets.

The reason should be obvious: the extraordinary flood of highly-paid tech workers and international capital into our region is pushing land values to obscene levels.

You’d never know that from reading Plan Bay Area 2013, which hails

…the Bay Area’s concentration of knowledge-based industries, research centers and universities; the presence of a highly educated and international labor force; expanding international networks serving the global economy; and the overall diversity of the regional economy. (34)

Two years later, MTC staff, at least, still seem oblivious to the tech tsunami’s devastating effect on affordability. Another item on the RAWG’s September 1 agenda is the latest edition of “Vital Signs: Environment,” MTC’s ongoing measurement of “regional progress towards key…policy goals” in Plan Bay Area. The cover memo, written by MTC planner Dave Vautin, says that Vital Signs “incorporates nearly 40 performance indicators and approximately 200 datas.”

But some critical information must be missing, because one of “the key findings of the overall project” is this astounding claim:

The region’s recent tech-driven economic boom has come about despite these affordability challenges; residents are faced with tough choices about living in America’s most expensive region or moving away to more affordable metros.

In fact, “[t]he region’s recent tech-driven economic boom,” has largely created the affordability challenges” in the Bay Area.

By contrast, Chion and Kirkey broach the contradiction between the smart growth thrust of Plan Bay Area and social equity. They write: “there is an inherent tension between the plan’s emphasis on focused growth within PDAs and patterns of displacement within the region.”

They must mean an inherent tension between focused growth within the PDAs and the residential stability of the region’s low-income population; “focused growth in the PDAs and patterns of displacement within the region” are in sync, not tension.

In 2013 regional planners themselves conceded that concentrating new development in the PDAs would inflate property values and force 36% of the region’s low-income people out of their homes.

Citing the Regional Early Warning System for Displacement that was recently published by UC Berkeley’s Center for Community Innovation, Chion and Kirkey report that

- of the 328,284 low-income households in the region, 205,313 (63%) live in PDAs.

- 82% of those households are at risk of displacement

Among the factors that, they say, “local efforts” to check displacement “must address” are

- Production and preservation of deed-restricted and/or market rate [?] affordable housing for low- and moderate-income households in PDAs, transit-priority areas (TPAs), and high opportunity areas

- Tenant protections, including “stronger just-cause eviction requirements and rent stabilization

- Allocating under-utilized publicly-owned lands for affordable housing

And at the regional level:

- A county or sub-regional commercial linkage fee on new office and commercial development

- Revenue-sharing mechanisms

But the list also includes an outlier:

- [l]and speculation and wild swings in housing costs that impact neighborhood stability (for example by carefully considering the amount of up-zoning of an area at any one time)

Well, upzoning is essential to facilitate dense, transit-oriented development. In a memo sent to the ABAG Administrative Committee in February 2015, Chion said that one of ABAG’s two top workplan priorities in 2015 was “to enable and assist jurisdictions to fully utilize state-sanctioned CEQA streamlining.” In February and May, [ABAG and MTC] hosted panels on “PDA Feasibility” and “Entitlement Efficiency” at which developers complained that excessive regulation at the local level was limiting housing production and making it impossible to meet the goals of Plan Bay Area.

In other words, Chion’s and Kirkey’s memo not only recognizes the “inherent tension between [Plan Bay Areas’s] focused growth in PDAs” and the residential stability of the region’s low-income population; it embodies that tension.

Now the work is to build on that recognition and to push for the passage and implementation of measures that enable “development without displacement.”

That pithy phrase is the name of the must-read 2014 study from Causa Justa, one of the signatories of the Six Wins letter. The full title is “Development without Displacement: Resisting Gentrification in the Bay Area.” The Executive Summary includes this:

The recommendations in this report stand in contrast to popular “equitable development strategies,” such as transit-oriented development (TOD), mixed-income development, and deconcentration of poverty approaches.

Rather than focus primarily on physical improvements or require the movement of existing residents, we suggest policies that empower local residents and communities with rights, protections, and a voice in determining the development of their own neighborhoods.

We also recommend policies that regulate government, landlord, and developer activity to promote equitable investment, affordability and stability, and maximum benefits for existing residents. (9)

Contrary to the above directive, the equity coalition buys into TOD, mixed-income development and deconcentration of poverty approaches to fighting displacement. In other words, it’s not just the staffs of MTC and ABAG who are—or should be—grappling with major contradictions.