The protests aren’t about technology — they’re about displacement, economic inequality, and bad corporate behavior. And they are part of a long political legacy

By Tim Redmond

FEBRUARY 18, 2015 – What if I told you there was never an anti-tech movement in San Francisco? What if I told you the Chron is completely wrong, and the alleged backlash against “tech,” which may or may not have ended, was never about tech in the first place?

What if it was part of a long legacy of communities resisting displacement, a history that goes back to the time just after World War II?

Let me tell you about it, because that’s a much more accurate narrative. And it’s important for people who throw around worlds like “anti-tech movement” need to understand.

First: The progressives, in a broadly defined way, were as much involved in the tech revolution in the early days as the libertarian types are today. Stewart Brand, a 1960s hippie type who created the Whole Earth Catalog and lived in a houseboat in Sausalito (way back before that would become chic) did as much to popularize the personal computer as Steve Jobs. The Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link, also known as the WELL, was the first community-building use of computer networking, and preceded the Internet by almost a decade. I had an account on the WELL in 1986.

Brand and Art Kleiner, who wore about technology for the Bay Guardian when I was first an editor there in the 1980s, created the Whole Earth Software Review in about 1983, when IBM was still figuring out the PC.

A group of decidedly anti-establishment leftish rebels called the Community Memory Project in Berkeley set out to create the first Google/Facebook, long before Sergei Brin, Larry Page, and Mark Zuckerberg were out of diapers.

The Bay Guardian has its own BBS, called Guardian Online, in the 1990s, and at one point we had about 10,000 regular users – again, long before the Internet became a force for shopping and ad sales.

The roots of the Bay Area tech world were much more in the 1960s hippie ethos than in the modern version of a money-driven world where vast fortunes are made quickly.

The other side of Luddites

The Left in this city and this part of the world has never been made up of technophobes. We were not Luddites in the usual sense of the word – although Thomas Pynchon gave a deeper understanding of the clash between technology and the working class in his famous 1984 essay, “Is it OK to be a Luddite?”

The knitting machines which provoked the first Luddite disturbances had been putting people out of work for well over two centuries. Everybody saw this happening — it became part of daily life. They also saw the machines coming more and more to be the property of men who did not work, only owned and hired. It took no German philosopher, then or later, to point out what this did, had been doing, to wages and jobs.

What was Pynchon’s hope in 1984?

But we now live, we are told, in the Computer Age. What is the outlook for Luddite sensibility? Will mainframes attract the same hostile attention as knitting frames once did? I really doubt it. Writers of all descriptions are stampeding to buy word processors. Machines have already become so user-friendly that even the most unreconstructed of Luddites can be charmed into laying down the old sledgehammer and stroking a few keys instead. Beyond this seems to be a growing consensus that knowledge really is power, that there is a pretty straightforward conversion between money and information, and that somehow, if the logistics can be worked out, miracles may yet be possible. If this is so, Luddites may at last have come to stand on common ground with their Snovian adversaries, the cheerful army of technocrats who were supposed to have the ”future in their bones.” It may be only a new form of the perennial Luddite ambivalence about machines, or it may be that the deepest Luddite hope of miracle has now come to reside in the computer’s ability to get the right data to those whom the data will do the most good. With the proper deployment of budget and computer time, we will cure cancer, save ourselves from nuclear extinction, grow food for everybody, detoxify the results of industrial greed gone berserk — realize all the wistful pipe dreams of our days.

The computer, once upon a time, was a tool that might “detoxify the results of industrial greed gone berserk.” Think about that for a second – and then think about what’s happened in the past three decades – and you get a sense of how those of us on the economic Left think about technology.

But let’s leave King Ludd for the moment and talk about displacement.

In the period right after the War, when American cities were mowing down neighborhoods to make way for the Era of the Automobile and a new sort of Progress, San Francisco’s civic leaders decided that they needed to remove “slums” (places where African Americans lived) in the Western Addition and clear out the low-income areas South of Market, where they envisioned a center for tourism: New hotels and a convention complex.

The result, as Calvin Welch describes it, was a “housing holocaust.” Tens of thousands of low-income units were demolished, and lower-income residents were driven out of town.

The communities fought back, with some noteworthy success. As Chester Hartman explains in his classic, “Yerba Buena: Land Grab and Community Resistance,” both tenants and property owners demanded that the low-income housing be replaced. Tenants and Owners Opposed to Redevelopment succeeded in getting thousands of affordable units build and created the Tenants and Owners Development Corporation, TODCO, which still builds and manages affordable housing in Soma today.

The battle of the Haight

By the time I arrived in San Francisco, in the early 1980s, neighborhoods like the Haight were facing another type of displacement. Downtown was booming, with banks, insurance, and real-estate operations moving into dozens of new highrise offices. They attracted well-educated college graduates, who had abandoned the suburbs where they grew up and decided they wanted to live in cities.

The young bankers and insurance types – we called them “Yuppies” – wanted to live in hip areas like the Haight. They had jobs that paid high wages; in fact, a group of musicians from Stanford, who were getting Master of Business Administration degrees, wrote a song with a chorus:

Hey hey we’re the MBAs

Don’t you see we’re the latest craze

Hey hey, the MBAs

Having fun earning twice our age

In 1984, earning $50,000 as a 25-year old was a huge salary. Easily enough to take over a sweet apartment that some senior citizen had been living in.

The management-level office workers were forcing working-class, often older residents out. The big winners, of course, were not the young professionals moving to the city but the landlords and speculators, who made a fortune on rising rents and property values.

The housing battles in those days were over rent control, eviction protections, and limits on condominium conversions – all aimed at preventing speculation and landlord price-gouging protecting existing residents from new arrivals who had more money.

Nobody (well, not that many of us) were against banks or insurance companies, per se. We just argued that we were building too much office space for these types of industries without considering the impacts on housing. (Yes, in the 1980s, people on the Left – the folks now blamed for the housing shortage – were the only ones demanding that the city and the developers build new housing. But development in SF is driven by international investment capital, and back then, the highest returns were in commercial office space. The private sector had no interest in building housing. And the mayor, Dianne Feinstein, refused to even consider demanding that developers build enough housing for their new employees.)

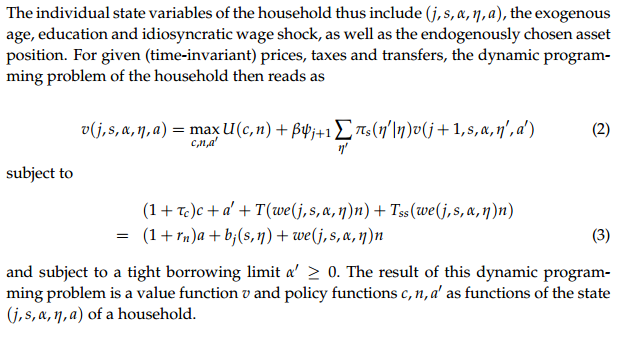

You think blocking Google buses is a heavy-duty tactic? You should have been around in the early 1980s, when a group called “The Mindless Thugs” tossed bricks through the windows of businesses that were catering to the Yuppie trade and demonizing homeless people.

Dot-com 1.0

When the first dot-com boom hit, in the 1990s, nobody I knew was anti-tech. Look back: The Guardian – possibly the most pro-tenant, anti-displacement publication in the nation – was running its own high-tech (for then) BBS. No: We were against richer people pushing poorer people out of their homes. And we were against commercial landlords who kicked out nonprofits to make room for dot-com companies.

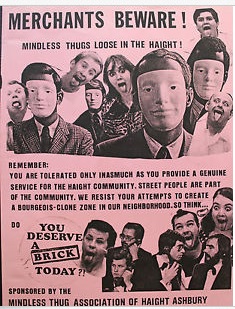

Again, it got rough: The Mission Yuppie Eradication Project encouraged things like scraping the paint off fancy cars and breaking windows.

There were moments of absurdity: On 22 and Mission, the Dancers Group Studio – home to numerous small dance companies – lost its lease so that the space could become tech offices. Across the street, nonprofits were forced out of the Bayview Bank building so that a dot-com could take over their space. On Bryant Street, an old warehouse that had been turned into studio space for more than 50 painters, photographers and other artists, was bought by a developer who evicted everyone and demolished the place to build a dot-com headquarters office.

All three of those dot-coms went bust. The Dancers Group building reverted to dance space; the landlords of the Bayview Bank had an empty building. And the developer on Bryant bailed, leaving a big empty hole for years that filled with water every time it rained.

In no case did city officials or planners have enough sense to say: No, this is too much, too fast. It’s not sustainable.

And it wasn’t, of course.

The tech industry has matured, a lot. Startups have actual products, with actual value. Companies like Google and Apple and Facebook have established markets and positive cash flow. We aren’t looking at another dot-com bust, on that level, any time soon.

What we are looking at is another wave, the most vicious ever, of wholesale displacement of longtime residents by people with more money.

At the same time, like the Luddites of the Industrial Revolution, we are seeing a vast expansion of social and economic inequality – and the huge fortunes made by a very few in the tech industry are very much a part of that.

The people who worked at the WELL and Community Memory were brilliant electrical engineers, hardware experts and software designers. They made the same amount of money as most people who worked in the nonprofit or small business world. There were no stock options, no instant billionaires.

Now, in the United States, a tiny number of people are making a whole lot of money, and lot of the rest of us who have seen our standards of living stagnate or decline.

Trains and sugar — and fair taxes

The trust busters who complained about robber barons at the dawn of the 20th Century weren’t opposed to railroads, oil wells, or sugar refineries. They were concerned by an undue concentration of wealth and power. Same today.

The tech revolution has made it possible for me, a refugee from print media, to start an online daily newspaper on a shoestring. Thirty years ago, I would have needed tens of millions of dollars to start 48hills; today, I need a few hundred bucks and a WordPress template. I use Facebook and Twitter to promote this site. I use Google every day.

There’s nothing bad about tech. There is something very, very wrong with an economic system that lets some people become rich beyond what anyone could ever need or want while the rest of society lags behind. And there’s something very wrong with a city that allows those people to push others out.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

After the bad money and excesses of the Gilded Age brought on the Depression, FDR saved American capitalists from the fate of the Russian aristocracy in part by making sure the rich paid real taxes. In 1936, incomes of more than $5 million were taxed at 79 percent. During the War, incomes over $200,000 were taxed at as much as 91 percent.

In 1955, incomes of $400,000 or more still paid 91 percent. That was during the greatest economic boom to that point in US history.

It wasn’t until the Age of Reagan that those rates were dropped to 50 percent, and in 1986, to 38.5 percent.

And – what a surprise – around that time the rate of economic inequality began to rise to the unsustainable levels of today.

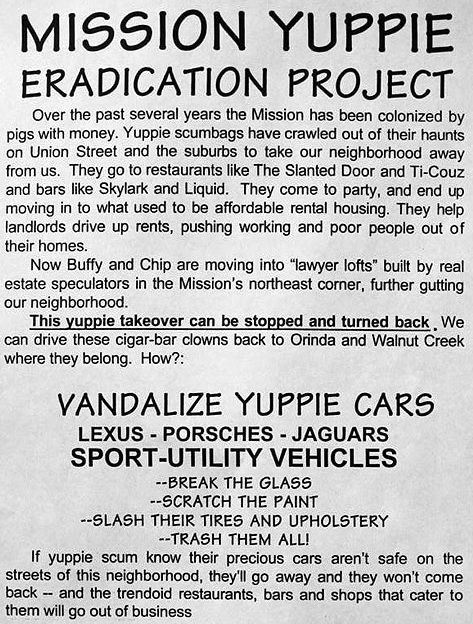

A recent paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research argues (not from a leftist ideology) that a marginal tax rate of 90 percent on the top1 percent would be best for a functioning economy. It’s a little dense, unless you really love things like this:

But it concludes that “high marginal labor income tax rates are an effective tool for social insurance.” They also create a larger middle class — and if you tax excessive income, there are fewer people with the money to drive poorer people out of town.

Does anyone really think that Zuckerberg would have given up on Facebook if he knew, as a college student in a dorm room, that his maximum net wealth would be around $3 billion instead of $33 billion? Can anyone seriously argue that $3 billion – that is, ten percent of his wealth — isn’t enough for any human being on Earth?

Would all those tech companies really have refused to move to Market St. without a tax break? (I know one would have: The folks at Zendesk told me very clearly at a meeting last year that they were coming to mid-Market anyway, that the payroll tax break was just gravy and they didn’t need it.)

Does anyone who wants to build more housing believe that the private market (again, driven by capital that seeks the highest return, which right now is luxury condos) can meet our needs by itself? Wouldn’t a sane housing policy involve the kinds of money (multiples of billions of dollars) invested in affordable housing in cities that would be available if we hadn’t cut tax rates on the very rich?

Let me try to quantify this. According to the federal government, in 2013 Americans earned about $14.17 trillion in income. About 40 percent of that went to the top 1 percent. That’s $5.6 trillion.

The average tax rate for the top 1 percent is 24.01 percent. If we raised that to 70 percent, we’d be talking about more than enough money to rebuild the housing stock in US cities, repair the social safety net, invest in education, reduce inequality … and still let the rich be pretty stinking rich.

The tech revolution over the past 20 years has created great wealth in the United States. It’s increased employee productivity radically. And none of that wealth has been shared; all of it has gone to the top 1 percent.

That’s a sign of a dysfunctional economy. In theory, productivity increases lead to raises for workers. That hasn’t happened in the United States in the past two decades.

In fact, you can argue that the bottom 99 percent has lost out in the boom; that’s certainly the case in San Francisco. When the wealthier newcomers drive up housing costs, that takes money out of the pockets of everyone else.

Corporations and government

Robert Reich says you can’t blame corporations for greedy behavior; that’s what corporations do – they make money for shareholders. The fault, he says, is with policymakers who allow this all to happen. Hate to say it, Libertarians, but it takes a strong government, willing to intervene in the economy, to make sure that wealth like what we’ve seen in the past 20 years in this country goes to improve all lives, not just a very few.

That starts at home: Mayor Ed Lee talks about a “city for everyone,” but he’s given away tax money the tech industry – and made no effort to require the richest to share.

Of course, corporations don’t just make money – they spend money to win elections and make sure that people who want to hold them accountable never have a chance. There’s a reason nobody is challenging Ed Lee, and it’s not his poll numbers. It’s money. Tech money.

Horrible economic inequality doesn’t spur innovation or improve the economy. Relentless displacement doesn’t make the city a better place.

We can argue over solutions to the housing crisis. For me, any answer begins and ends with the idea that people who already live here get to stay, no matter how much money they make, and people who are richer don’t get to push them out. That’s been the argument the Left has made since the 1950s, and the fact that tech workers instead of hotel developers or Stanford MBAs are the ones moving in is irrelevant.

And any answer also involves large amounts of public money, which can only come be forcing the uber-rich to pay more in taxes.

But this isn’t a war on “tech.” The people blocking Google buses, and demonstrating in front of Twitter, are using Google for research and tweeting photos of their actions. It’s not about technology, and it never has been.

There are tech companies that do bad things, and we will protest them – just as we protest bad banks, and clothing manufacturers, and other villains in corporate America. But those are individual corporations; the concept of advanced technology goes way beyond its worst actors.

The sci-fi world is full of stories of technology gone too far. (One of them helped put an actor in the California governor’s office.) But humans can control technology, to direct its use to areas that are beneficial to society. Humans can control the economy, too.

See, in the end, to quote a much younger Bill Clinton, it’s really the economy, stupid. It’s about wealth concentration and displacement – and while some tech workers are helping, overall the industry (like the redevelopment mavens of the 1950s and 1960s, and the office developers of the 1980s, and the real-estate speculators who are making bank out of all of this pain) isn’t doing much of anything to change an unsustainable system that at some point is going to collapse on all of us.

That’s what people are protesting. For good reason.

And let’s remember: The protests in the past — crazy, mild, and everything in between — have been the root of every good tenant-protection law in San Francisco. The reason any of us are left to protest is because there’s a long legacy of people who have fought displacement for generations, bringing us rent control, eviction protections, condo-conversion limits, protections for SRO hotels, affordable housing mandates …. those didn’t come from City Hall. They came from the streets.

And that continues today.