It’s hard not to be riveted by the terrifying advance of Donald Trump’s presidency. But it would be a huge mistake to ignore less sensational exercises in autocracy, especially those occurring at home. One such operation, which has gone virtually unnoticed, is the continuing travesty of democratic governance known as Plan Bay Area.

Mandated by SB 375, the Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act of 2008, Plan Bay Area is our nine-county region’s Sustainable Community Strategy—a so-called blueprint that knits together transportation and land use plans and investments for each region in California so as to accommodate the area’s projected growth of jobs and households and at the same time meet its official greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets.

Unelected officials run the show

Plan Bay Area’s autocratic character is rooted in the un-democratic governance of the regional agencies under whose aegis it proceeds, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and the Association of Bay Area Governments. Both entities are putatively overseen by unelected officials—to be precise, elected officials (mayors, city councilmembers, and county supervisors) who were not elected to serve on MTC or the ABAG Executive Board. It follows that when they run for office or re-election, their positions on Plan Bay Area and the regional agencies’ other projects never come up.

Scott Wiener sits on MTC, and Jane Kim is on the ABAG Executive Board, but during their hotly contested campaigns for state senate, nobody asked about MTC’s hostile takeover of ABAG last May (Wiener supported it—vociferously, accusing opponents of “throwing rocks at MTC”; Kim was absent for the Ex. Board’s May 19 vote on the matter) or their positions on Plan Bay Area’s gigantic growth forecasts and allocations for San Francisco and the 11th State Senate District, and its implications for displacement and housing affordability or local control of development.

Augmenting the democratic deficit, both MTC and ABAG are effectively led by staff, not their governing boards, whose members have no staff of their own, and whose obligations to their local jurisdictions in any case preclude their delving into the copious details of regional policy. Since MTC’s coup, ABAG staff report to MTC’s peremptory executive director, Steve Heminger.

After a stormy public planning process, the first edition of Plan Bay Area was approved by MTC and ABAG in July 2013. State law requires each Sustainable Community Strategy to be updated every four years. Plan Bay Area is well into its first quadrennial update. On November 17, following a perfunctory deliberation, MTC and the ABAG Executive Board approved a Final Preferred Scenario and Investment Strategy that will serve as the conceptual template for the update. The fully realized blueprint-cum-Environmental Impact Report is to be finalized next summer or fall.

A farcical public process

Plan Bay Area’s autocratic character is exacerbated by its superficial public planning process. Compared to the public process that culminated in Plan Bay Area 2013, the update proceedings have been uncontentious. That’s because most of the individuals who participated in the first round haven’t shown up for the second one—for a good reason: they’ve realized that the meetings are a time-consuming sham that exist only because SB 375 requires some form of public outreach. No meaningful input could possibly emerge out of the cursory, often infantilizing, staff-dominated activities that the regional agencies peddle online and at their workshops and open houses.

The only members of the public who’ve continued to participate are those who are paid to do so: representatives of the non-profits that weighed in on round one. This motley crew includes equity and housing advocates (Urban Habitat, Working Partnerships USA, Public Advocates, Non-profit Housing Association of Northern California, 6 Wins for Social Equity Network), environmental organizations (Greenbelt Alliance, the Sierra Club), transit promoters (TransForm), and lobbyists for big business and big property capital (SPUR, the Bay Area Council, the Building Industry Association, the Silicon Valley Leadership Group).

Their considerable political differences notwithstanding, these organizations have two things in common: they all accept Plan Bay Area’s growth-to-the-max premise; and, however righteous their missions and valuable their work, they’re all private entities that are ultimately accountable to their donors and their boards of directors, rather than to any public electorate.

The planning process is also rushed. The regional agencies issued a Draft Preferred Scenario on September 2. On October 14, only six weeks later, public comment on the scenario was closed. The Final Preferred Scenario and Investment Strategy was released on October 28 and approved just three weeks later on November 17.

The regional agencies seem to show the local jurisdictions little more respect than they offer the public at large. During the takeover fight last spring, ABAG contrasted its attentiveness to cities, meaning cities’ planning directors and county transportation congestion management agencies, with MTC’s haughtiness.

Perhaps because MTC is now in charge, this fall such solicitude was in scant evidence. In late October, staff to the San Francisco County Transportation Agency, San Francisco’s congestion transportation agency, said that they had yet to be fully briefed about the update by MTC and ABAG.

By October 20, forty-one jurisdictions had commented on the Draft Preferred Scenario. MTC and ABAG staff stated that they would respond to all comments by the end of December—a month and a half after the Final Preferred Scenario was to be approved.

Wild numbers

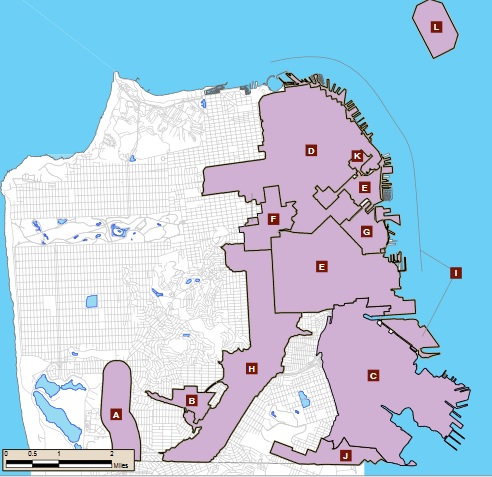

To achieve its arguably unachievable double goal of accommodating all of the region’s forecasts new jobs and households and at the same time meeting its greenhouse gas reduction targets, Plan Bay Area directs most new residents and employment into so-called Priority Development Areas, existing neighborhoods near transit. San Francisco has twelve PDAs.

The forecasts or projections—we’re not supposed to call them predictions—for San Francisco are wild. Plan Bay Area 2013 expected the city to accommodate 15% of the region’s total growth through 2040, measured against a 2010 base: 92,480 more housing units and 191,000 more jobs—a 25% and 34% jump, respectively.

The numbers in the Plan Bay Area 2017 Final Preferred Scenario are even crazier.

Plan Bay Area 2017 update: Final Preferred Scenario

Household and Employment Forecasts for San Francisco

|

Level |

Households 2010 |

Households Forecast 2040 |

Employment 2010 |

Employment Forecast 2040 |

|

Total |

345,811 |

483,700 (+137,889 or 40%) |

576,850 |

872,500 (+295,650 or 51%) |

|

PDAs |

182,430 |

310,100 (+127,670 or 59%) |

473,990 |

741,700 (+267,710 or 64%) |

At an average household size of 2.4 people, we’re talking about 1.1 million residents in this geographically limited city.

The big numbers are more meaningful broken down by PDA. High-level city planning staff are still negotiating the PDA allocations with MTC and ABAG. Here are a few of the biggest increases in the Draft Preferred Scenario:

|

PDA |

Household 2010 |

Household Forecast 2040 |

Employment 2010 |

Employment Forecast 2040 |

|

Bayview/Hunters Point Shipyard/Candlestick Point |

10,300 |

32,450 |

25,250 |

43,250 |

|

Downtown-Van Ness-Geary |

84,300 |

109,500 |

244,150 |

362,500 |

|

Eastern Neighborhoods |

35,550 |

56,900 |

78,600 |

107,850 |

|

Transit Center District |

800 |

5,650 |

59,500 |

119,050 |

Eroding local control

MTC and ABAG repeatedly assert that nothing in Plan Bay Area constrains local control of development. The October 28, 2016, ABAG/MTC staff memo re the Final Preferred Scenario and Investment Strategy states:

[T]he Final Preferred Scenario does not mandate any changes to local zoning rules, general plans or processes for reviewing projects, nor is it an enforceable direct or indirect cap on development locations or targets in the region. As is the case across California, the Bay Area’s cities, towns and counties maintain control of all decisions to adopt plans and permit or deny development projects.

Strictly speaking, this is true. No jurisdiction can be legally compelled to designate a Priority Development Area. The region’s 191 PDAs were all nominated by local jurisdictions. San Francisco’s PDAs were unanimously approved by the Board of Supervisors in 2007.

And even if a city does designate Priority Development Areas, it can’t be legally forced to approve the number of new housing units that it’s been allocated—at least, not yet.

At the November 17 meeting, held at the regional agencies’ fancy new digs on Beale St., Heminger asserted that the regional agencies needed to get the authority and the funding to build housing to accommodate the region’s entire population.

In response, State Senator-elect Wiener described the current housing scene as “a slow-moving train wreck” and asked, “What is the path to figuring out how many units we need…to stop the bleeding?” (I’ve asked both Wiener and his supervisorial staff whether he supports state legislation that would compel cities to approve the housing they’ve been allocated by Plan Bay Area. So far, no reply.)

Heminger estimated that it would take “over a million” new housing units “to make a dent in the shortfall.” The real challenge, he said, is “to fit that growth in the communities we cherish,” adding, in a non sequitur: “We need to change what the Bay Area looks like.” Heminger noted that such a transformation would require the “legal enforceability” that the regional agencies now lack. He told Wiener: “We’ll be on your doorstep asking for the money and authority to carry it out.”

Heminger’s call for ending local control of residential development was echoed by two new members of the ABAG Executive Board representing San Francisco, both Mayor Ed Lee’s appointees, Planning Department Senior Policy Advisor Anne Marie Rogers and Community Planning Manager Joshua Switzky (The city has four representatives on the board: two supervisors, currently Kim and Mar, and two representatives of the mayor). Rogers called for “enabling legislation” that would provide “the tools we need.” Switzky said, “We need to have the courage to push cities to accept the plan.”

In fact, cities’ prerogatives are already constrained by SB 375 and its statutory progeny. For example, under SB 743, passed in 2013, a development that’s “consistent with a sustainable communities strategy” cannot be challenged under the California Environmental Quality Act on the basis of its “growth-inducing impacts.”

Moreover, a jurisdiction that doesn’t get with the program is going to be moved to the back of the line for money from the regional agencies, especially from MTC, which controls billions of dollars of discretionary transportation funding. That’s a big deal; infrastructure drives development. Without the envisioned new transit, getting 295,000 new workers in and out of San Francisco is going to be well-nigh impossible.

The top staff to the San Francisco County Transportation Authority, whose governing board comprises the city’s eleven supervisors, sent the SFCTA a memo dated October 5 recommending approval of the city’s input on the Plan Bay Area 2040 Draft Preferred Scenario that they were proposing. Referencing the scenario’s Transportation Investment Strategy, the memo lists forty-one Projects in San Francisco and Multi-County Projects of Interest to San Francisco whose total cost comes to $17.6 billion.

The big-ticket items include transit preservation and rehabilitation ($2.26 billion), expanding the Muni transit fleet ($1.5 billion), the Presidio Parkway ($1.6 billion), and the next phase of the Central Subway ($1.6 billion). Another twenty-nine regional and multi-city projects, including the BART Transbay Core Capacity Project ($3.4 billion), high-speed rail in the Bay Area ($8.4 billion), the first phase of Caltrain electrification ($2.4 billion), and the Caltrain/HSR downtown San Francisco Extension ($4 billion) will cost a total of $246 billion.

Unsurprisingly, SFCTA Executive Director Tilly Chang’s October 18 letter to MTC and ABAG commenting on the Draft Preferred Scenario, co-signed by San Francisco Planning Director John Rahaim and San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency Executive Director Ed Reiskin, opened on a propitiatory note:

Overall we appreciate that the transportation investment scenario supports San Francisco’s transportation policy and project priorities, which is critical given the land use scenario’s proposal for the City to absorb a great amount of the region’s jobs and housing growth through 2040.

No public deliberation in San Francisco

The Preferred Draft Scenario never came before the Board of Supervisors. It appeared only on the agenda of San Francisco County Transportation Authority, the congestion management agency for the city and county of San Francisco. SFCTA’s governing board meets on the fourth Tuesday morning of every month. Staff proposal for San Francisco’s input on the Preferred Draft Scenario was on the Authority’s September and October agendas. At those meetings, not one supervisor asked a question or remarked on staff’s proposed comments to MTC and ABAG. Nobody spoke at public comment. On October 25, the SFCTA unanimously approved the staff recommendations.

The absence of public deliberation is stunning. To be sure, the Draft Preferred Scenario was issued just two months before a highly contested election. People were otherwise preoccupied. And no doubt supervisors and staff were in consultation behind the scenes, which likely explains why the regional agencies dropped their initial expectation that San Francisco’s cap on annual new office development would be eliminated. But given what was at stake, the city’s response should have been a high-profile topic.

The Planning Department should have sponsored substantive community briefings about the update—one meeting in each PDA would have been ideal—solicited and documented residents’ informed responses to the growth projections, and incorporated those responses in the city’s comprehensive comments. It did not. Not incidentally, the draft PDA allocations are not posted on either the city’s or Plan Bay Area websites; I had to ask city staff to provide them.

I asked Calvin Welch, dean of the city’s community activists, whether the Planning Department had ever briefed any neighborhood about a Priority Development Area. His reply: “I know of no specific briefing or notice given to either community organizations or neighborhood groups in these specific neighborhoods.”

The city’s ambiguous response

So we are left with the staffers’ October 5 memo and October 18 letter as statements of the city’s position on the massive growth that the regional agencies expect it to absorb by 2040. As it contemplates those expectations, the October 18 letter moves from appreciation to apprehension to outright opposition. It’s not that the authors are anti-growth. Quite the contrary. It’s just that even they can’t help blinking at the enormous numbers. Watching them grope for language that expresses their unease but doesn’t offend their powerful patron, MTC, is almost comical. But their overall take is alarming.

On housing growth: Though “the [projected] housing growth…far exceeds both historic and recent annual average production numbers, and the 128,000 units proposed in the Draft Preferred Scenario “is a 33% increase over PBA 2013 allocation,” they “feel” that “the land use scenario assumptions for San Francisco are ambitious but achievable,” as long as the city is given “substantial additional revenue sources and new policy tools,” as well as “commensurate transportation investment.”

On jobs growth: “The aggregate jobs allocation for San Francisco,” they write, “is 70% higher than the PBA 2013 (311,00 vs. 190,00).” The regional agencies reduced that figure to 267,710 in the Final Preferred Scenario.

While plausible, this depends substantially on densification of existing space….Densification in existing space is a key aspect of capacity that the City cannot regulate or affect [untrue] and can mostly just speculate as to potential overall capacity and likelihood or pace of such absorption.

On transportation funding:San Francisco has successfully secured local revenues for transportation and housing and is continuing to seek additional revenues given insufficient and reliable state and federal funds….However local funds are not enough to meet our needs as one of the three big cities taking on the most job and housing growth in PBA 2040….We want to ensure we are receiving a commensurate share of regional discretionary dollars and [are] not being penalized for seeking and securing new local dollars.

On the distribution of new housing units among the city’s Priority Development Areas: Here Chang, Rahaim and Reiskin drop the conciliatory gestures. “Distribution of growth within San Francisco should reflect local plans”[emphasis in original). Despite the fact that since May, the “Planning Department has been working with ABAG and MTC staff to make final redistributions of proposed growth within the city to align with current plans and policies,” at the PDA level there are “unrealistic discrepancies that should be rectified.”

For San Francisco, notable over-allocations were shown on the housing side to Mission Bay, Bayview/Hunters Point Shipyard-Candlestick, Treasure Island and the Port, and on the jobs side to Downtown-Van Ness-Geary, Balboa Park, Mission Bay, and non-PDA areas.

On social equity: The trio objects even more strenuously to the Draft Preferred Scenario’s negative implications for social equity. SB 375 says nothing about social equity. Under pressure from the 6 Wins for Social Equity Network, a coalition of non-profit equity advocates, the regional agencies added social equity targets dealing with anti-displacement, and housing and transportation affordability to Plan Bay Area 2013. In preparing for the 2017 update, MTC staff tried to remove the anti-displacement target; ABAG staff wanted to keep it in. An ugly public fight ensued. Thanks to the 6 Wins Network’s effective organizing, the anti-displacement target survived. But Plan Bay Area 2017 is going to miss all three social equity targets—badly.

Adequate housing/community stability: By the regional agencies’ own reckoning, the inflated property values generated by the new development projected by Plan Bay Area 2013 were going to put 30,000 households at risk of displacement. The target in the Draft Preferred Scenario holds that risk steady. Instead, MTC and ABAG staff expect the growth forecast by the Draft Preferred Scenario to increases the risk of displacement by 9%.

Equitable access to transportation and housing: The target decreases transportation and housing costs for lower-income households by 10%. Instead, those costs will increase by 13%.

Affordable housing: The target increases the share of affordable housing in the Priority Development Areas, Transit Priority Areas and high-opportunity areas [too much plannerese to unpack in this story] by 15%. Instead, the share will increase by just 1%.

The equity failures elicited the San Francisco staffers’ unequivocal condemnation. “Despite these ambitious goals [the jobs and housing growth],” they write, “the Draft Preferred Scenario fails to meet the Plan’s affordability and anti-displacement targets, and this outcome is simply unacceptable.”

Agreed, at least as far as the unacceptability of the equity shortfalls is concerned.

The Chang/Rahaim/Reiskin analysis of those shortfalls is another matter. The projected equity failures will occur, not as the threesome assert, despite the “ambitious” jobs and housing growth, but rather because of them. The affordable housing crisis reflects the influx of tens of thousands of highly paid tech workers into the city—an influx encouraged by Ed Lee and his administration (for starters, think the Mid-Market “Twitter” tax exemption). Predictably, the word “tech” does not appear in the five-and-half-page single-spaced letter. Any analysis that omits that term is deeply flawed.

Like their assessment of the Final Preferred Scenario, the department heads’ proposals are ambiguous. Their recommendations for protecting existing rental units and tenants and enabling production of new below-market-rate rental housing are excellent:

- Reform the Ellis Act to allow local jurisdictions to limit removal of rental units and to provide for adequate relocation costs commensurate with local conditions

- Reform the Palmer court ruling (no inclusionary housing in rentals) the Palmer ruling (no inclusionary housing in rentals), and the Costa Hawkins law, so as to allow new rental housing to be rent-restricted.

But their overall analysis echoes the real estate industry’s misguided build, baby, build gospel. For Chang, Rahaim, and Reiskin, the main sources of the region’s housing crisis are “constraints in production, many cities not doing their part, lack of funding, and no teeth to enforce the Plan.”

They suggest two ways of expediting the production of affordable housing:

- A regional measure to enact a regional jobs-housing linkage fee (i.e., assessed on new commercial construction to be used for affordable housing), whereby cities would be exempt if they already have a fee or adopt their own fees equal to or greater than the regional fee

- A regional pilot program “to see what it really takes to produce affordable housing” in different kinds of places (big city, suburb), ideally using regional funds to leverage local dollars in two or three locations “facing high displacement risk”

Fine. But their overarching proposal for addressing the affordability crisis is inexpedient: pursue “state legislation to increase housing production and compel local jurisdictions to zone for and entitle housing consistent with regional sustainable communities plans.” They don’t explain why building all the new housing envisioned by updated Plan Bay Area 2040 would help people, especially poor people, who can’t get into the current housing market find shelter. Presumably they believe in the supply and demand argument, which has been repeatedly debunked (here and here). If they have a different theory, I’d be glad to hear it.

In any case, forcing cities to approve the housing units they’ve been allocated by Plan Bay Area 2017 is a bad idea. It’s undemocratic, replacing local control of development with de jure control by unelected officials and de facto control by the real estate industry. Yes, cities can and do refuse to build affordable housing because they don’t want poor people in their neighborhoods. That’s wrong and reprehensible. It’s also illegal. But what drives the real estate industry is neither social justice nor economic democracy; it’s maximizing the rate of return on investment—a motive that, as we’ve recently been seeing, leads to inflated property values, greater inequity, displaced tenants, and fractured communities.

Missing: fiscal impacts, water issues, quality of life, community character

The build-to-the-max position espoused by San Francisco officials and Plan Bay Area raises grave issues that are off the table.

Fiscal impacts: Those 138,000 additional households and 295,650 additional workers are going to need sufficient new services besides transit: schools, police, firefighters, parks, public works. How much will they need, and how will those will those services be funded?

Water: SB 375 narrows environmental sustainability to addressing climate change. What about resource depletion—specifically, water? California is in a long-standing drought. In October scientists at the Bay Institute reported that the diversion of rivers has led to the near-collapse of the San Francisco Bay ecosystem. How much water are those 138,000 additional households and 295,650 additional workers going to consume? Where is the city going to get it?

These questions seem obvious and urgent, but at the November 17 meeting, the issue of water supply was raised by only two voting officials, neither one from San Francisco: Novato Mayor Pat Eklund and Hayward Mayor Barbara Halliday, who sit on the ABAG Executive Board.

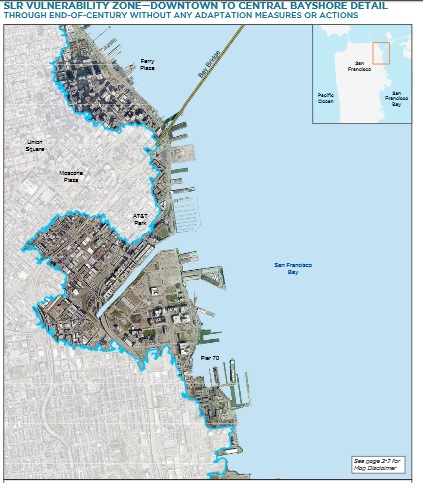

And what about the other water problem—sea level rise? Nonsensically, Plan Bay Area channels a good deal of San Francisco’s projected construction into the Eastern Neighborhoods, where sea level rise is a growing concern.

Quality of life/overcrowding: Most of the forecasted growth would go into parts of San Francisco—what planners are calling the downtown core, plus the southeastern and southwestern neighborhoods, where traffic congestion and transit system crowding were—and are—already acute. SB 743 eliminated traffic congestion as an environmental impact for infill projects under CEQA.

And there are other kinds of congestion. In what turned out to be his final story for the Bay Guardian, a critical look at Plan Bay Area that raised many of the issues I’m flagging here, Tim Redmond asked his readers to imagine ten thousand people headed for Dolores Park on a weekend. Think about it.

Ballot box rebellion in the burbs

Defying the growth autocracy is a daunting task, if only because its leading supporters—the real estate industry moguls now joined by the tech oligarchs—pour millions of dollars into local politicians’ campaigns for office. But those powers are not invulnerable.

On November 17, after Heminger, Rogers, and Switzky had advocated changes in state law that would enable MTC and ABAG to force cities to approve the new housing stipulated by Plan Bay Area, Alameda County District 1 Supervisor and MTC Commissioner Scott Haggerty reported that on November 8 every incumbent in his district had lost. The yard signs, he said, all railed against “rampant growth.”

Haggerty’s geographically enormous district includes Fremont, Livermore, and Dublin—all scenes of massive new development (Dublin, said the supervisor, is the second fastest growing city in California)—and Highway 580, a road that’s become synonymous with gridlock.

To Haggerty, the incumbent wipeout didn’t suggest that it’s time to re-think the growth imperative. True, he questioned the big numbers, asking where they came from. Given his many years in leadership role on both the ABAG Executive Board and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the query was disingenuous.

Haggerty’s answer—the big numbers came “not from any elected officials,” but from the state’s department of Housing and Community Development—indicated his real concern: the voters “are starting to rebel” against big growth. “They did at the ballot box this year, and they’ll do it again and again,” he declared. To stave off further such rebellion, he wants more money for transit, money that, he complained, “you,” i.e. Plan Bay Area 2013, “didn’t give me.”

Palo Alto Councilmember Greg Scharff, who sits on the ABAG Executive Board, agreed. Scharff warned his colleagues: “If we don’t solve the congestion problem, you’re not going to have the political support to build the housing.” More ominously, he added: “If you really want to see an insurrection,…start talking about taking away local control.”

Would San Franciscans join a slow growth revolt?

Not, to state the obvious, if it’s made in the name of protecting suburban character.

Otherwise, the answer is unclear, at least judging from the results of the November 8 election.

The voters decisively (65% No) rejected Prop. K, which would have boosted the local sales 8.75% tax by .75% to pay for homeless services and Muni improvements. Perhaps they were confused: they just as decisively (66% Yes) supported Prop. J, which would have amended the City Charter to pay for the services and improvements that K would have funded. Or perhaps they objected to a regressive sales tax/new set-aside for Muni. Prop. K’s defeat nullified Prop. J’s passage.

On the other hand, the voters narrowly (52% Yes) approved Prop. O, which allows Lennar Corporation a special exemption to build five million square feet of new office space at Candlestick Point and Hunters Point without regard for the city’s annual limit of 950,000 sf of new office space or the transit needs of the project’s 8,000 new workers. Did Prop. O’s passage indicate that pro-growth sentiment now (barely) prevails in San Francisco? Or does it reflect the fact that the measure’s opponents spent zero, and its supporters spent $2 million dollars and still only eked out a victory?

In any case, San Franciscans ought to demand that the supervisors, their elected representatives, publicly vet Plan Bay Area’s big-picture growth agenda. Democracy, like autocracy, begins at home.

Note: For an incisive critique of the Draft Preferred Scenario’s equity failures, see the 6 Wins for Social Equity Network’s October 13 letter to MTC and ABAG.

What’s wrong with having one million people living in SF? Should there be a magical threshold in place?

ignore alcohol, drugs and bad choices. That is why most homeless are in their predicament.

MTC lost all credibility when they moved their offices to SF from Oakland, at a colossal cost. The Emperor must have his throne in the heart of the beast.

If you care about the environment and future generations, you will support more development here. Urban dwellers use far less resources than suburbanites.

That is crazy! Just say NO to 1 million San Franciscans. We should move jobs OUT of the City, and into areas where there is enough space to accommodate more housing.

Last Month, the PUC started adding more chemicals to our pristine Hetch Hetchy water, so it would be OK to drink since they are mixing reclaimed water that otherewise would be unsuitable to drink. Why? because we need more water for more residents.

I recommend this article to all Bay Area residents, although the examples primarily refer to SF. ABAG plans heavily impact Palo Alto, where I live and the rest of the Bay Area. There are no plans for increasing moderate income housing. There are other ways to manage sustainable growth other that doing that which most enriches developers. That is why zoning exists. We all need to involve ourselves in our local planning to hold our elective officials responsible for providing infrastructure (schools, roads, mass transit, water etc.) for growth, before it is built, not after along with plans that will ensure new housing for all income groups, not just the 1%. I don’t know of any new rental housing from Redwood City to Mountain View that isn’t charging $3K+ for one bedroom apartments and $5K+ for two bedrooms. This is not sustainable.

Is your point that those were last to arrive pay more for housing?

Property owners are more insulated from changes in the housing market. The best way to ensure one’s ability to stay in the City and to reduce one’s anxiety over rising rents, is to own. After being owner-move-in evicted many years ago, I saw the light. It motivated me to make major lifestyle sacrifices to become an owner.

The increase in condo conversation comment was to make ownership more affordable for the middleclass Generally, owner occupied stable neighborhoods are nicer than renter occupied transient neighborhoods. Neighborhoods benefit from owners. Reducing the rental stock to increase the ownership stock is a good thing in my estimation.

There are families with children in apartment buildings but not plenty, and they are more likely to be pre-school age children. Families with school-age children are more likely to be found in single family neighborhoods. There is a correlation between lower density, single family, owner occupied and families with children, and stronger correlation with school-age children. However, it is possible that if there were more 3-4-bedroom condo units being built we would see more families with children in apartment buildings. It seems that most condos are smaller one and two bedroom units.

Neighborhoods with flats have more children than neighborhoods with condos with 20 or more units, but not as many as single family neighborhoods. For example, Duboce Triangle has the highest percent of 2-4 unit households in the City but has one fifth the percent of households with children than Sea Cliff. The number of households with children in Sea Cliff is three times higher than the number in Duboce Triangle even though Duboce Triangle has twice as many households. 24-25% of Sea Cliff households have children compared to 6-7% in Duboce Triangle.

Typically, families with children are created in apartment buildings and move to single family homes as their families and incomes grow. With the limited supply of single family homes in the City, it often means moving out of the City. On my block the most recent families with children that moved in lived in the Inner Sunset and NOPA. One rented the other owned a unit in a condo conversion. We also have Latino families that migrated from the Mission.

The problem is the supply not affordability. There is no correlation between property values or household income and households with school-age children. Although, family households in lower income single family areas tend to have larger families. As the housing prices in my neighborhood have risen dramatically and so has the number of school-age children. They are just higher income families.

Urban decay has been defined by others. I did not say the decline of the middle class is a necessary evil for combating it. I said the reverse of gentrification is decay. A trend up is better than a trend down. High income areas are nicer than low income areas. Higher income people moving into my neighborhood have improved it; Not that it was bad before.

Urban decay can result from the loss of the middle-class or working-class. Urban blight can be reversed by the working-class moving back. Gentrification often begins with the middleclass moving in. I recall when Noe and Eureka Valley were going downhill. The Gays started gentrification in the Castro 45 years ago, and it slowly creeped east. The Mission gentrification began with the middleclass but the gentrifiers now being gentrified.

I don’t know about statewide or areas outside the Bay Area but reading the papers suggest that Antioch/Pittsburg was the first to have problems finding teachers. Santa Rosa offers higher pay but has recruitment problems. I think schools down the peninsula also offer higher pay and are having problems. Every district complains about the teacher shortage. Of course, housing prices in those areas have also increased.

I agree commuting is not the only measure of quality of life. People commute to improve their quality of life. It all depends what one desires or values.

The teacher shortage is statewide but is worst in urban areas, and the fact that SF is more competitive than some areas with lower cost of living does not mean that increased cost of living isn’t making SF less competitive over time. Similarly, the relevant comparison is not vs. all workers but vs. teachers several years ago (and even then, living in the city vs. commuting is not the only relevant measure of quality of life, as the restaurant survey shows).

You still haven’t really defined urban decay or said why you think the decline of the middle class is a necessary evil for combating it. As it is I’m not really seeing what urban decay has to do with your neighbors — in, as you say elsewhere, an owner-occupied single-family area — having moved to follow Bank of America.

My point is that the numbers for any given year include people who have been living in a city for the last ten-plus years in addition to people who moved within the last five. People in that first group will tend to be more insulated from changes in the housing market than people in the second group, particularly if they are property owners.

Your speculation that upzoning would drive families out of the city seems backwards to me. Plenty of families are willing to live in apartment buildings or other multi-family units; the problem is affordability. If 2-story, single-family units in the Sunset were replaced with 6 story apartment buildings, that would give families more opportunities to stay in SF, not fewer.

I am also pretty baffled that your solution to this is to *increase* condo conversions — i.e., increasing evictions and depleting rental stock.

Gentrification has reversed urban decay in most Western urban centers. The depletion of the middle-class in SF has been occurring for decades. Middle-class jobs are being depleted. In my neighborhood over the past 40 years many have moved because their jobs moved: Fireman’s Fund to Marin, Chevron and Pac Bell to the East Bay, BofA to Concord, and so on. Some close to retirement or if their spouse worked in the City of the opposite direction stayed. Families that did move often got newer, bigger, better homes, better schools, and better weather. Some miss the City but most are happy with the move.

It is true that many lower-wage jobs are critical to the City. We still have those services. So, the loss of those services appears to be a theoretical future effect. However, we are probably paying more for those services which adds to the cost of living.

The teacher shortage is Statewide. The price of housing is not the driving force. SFUSD has less of a problem recruiting and retaining teachers than other districts with higher pay and lower price housing. However, we could be more competitive if we raised their wages. It is interesting that, per SFUSD, 70% of teachers live in the City. That compares to the 38% of all workers who live in the City. The City is more affordable for teachers than the average worker? In my youth, all the young single teachers I knew had roommates. All the teachers I have known an older person had an employed spouse.

Looking at what numbers for the people who moved within the last five years? The trends will show the differences year-to-year. What point are you making? People have been leaving the City for more affordable housing for decades. In my 74 years, most of my childhood friends and all my relatives moved out of the City. They were mostly middle- and working-class. Rather than degrade their quality of life leaving the City improved it.

There is a long-term gentrification trend that started 50 years ago. Young educated have been migrating to SF in large numbers for decades. That talent pool attracted employers with higher paying jobs. Those talented young people have replaced the working class. Tim Redmond may be an example. I would bet the house he now lives in was occupied by a working-class family in the past.

The effects of the long-term gentrification trend are more noticeable when the economy heats up. There have been multiple housing “crises.” It is true the ownership is the only sure way to be secure if one wants to live in the City. It seems we have policies that make ownership less affordable. If limits on condo conversion were eased and the affordable housing percent were eliminated, we would see more middle-class being able to afford to own.

I live in an owner-occupied single-family neighborhood. The benefits of living there are obvious to most. One of quality of life issues is the higher percent of families with school-age children. If upzoned it would drive more families with children out of the City. I support more housing being built on the East Side as it takes pressure off my neighborhood.

I responded above but the trend over time is important because the current numbers include a lot of people who are insulated from the current crisis by having moved when housing prices were considerably lower, either benefiting from rent control or from property ownership.

I suspect you really need to look at the numbers for the people who moved within the last five years, specifically. People who moved before the current housing crisis, and particularly people who own property, are likely to be insulated from the worst of its effects.

I also think there’s some irony that you oppose upzoning because of some supposed potential degradation in your quality of life, while taking the position that the real, currently-observable degradation in quality of life caused to middle- and working-class renters by the current unaffordability of housing is totally fine. This seems like it could only be consistent if you assume that land-owners and property-owners should have more of a voice in society than working-class and middle-class renters.

It is at least refreshing to hear explicitly that property owners (and some beneficiaries of rent control) would rather people in my income bracket have more austere, difficult, and unstable lives than allow any more housing to be built in SF. I think people with this opinion don’t really have any business calling themselves “progressives,” but at least it’s an intellectually coherent position.

What do you mean by “urban decay”, exactly, and why do you associate that with the depletion of the working and middle class from SF?

It sounds like you’re taking the position that the working and middle classes being pushed out of SF is fine or even desirable – is that a fair reading of your comment?

Also, many lower-wage jobs are of critical importance to the city and can’t simply be replaced by high-paying tech jobs. To pick just one example, if public schools can’t attract and retain good teachers, that has negative externalities for everyone who relies on the public school system.

2014 is the most recent census sampling. It is the number of primary jobs. The percent of the jobs in SF of the total for the Bay Area does not change much year to year. The fact is 80% of the Bay Area jobs are outside of SF no matter what data you are looking at. I am not sure how density is relevant. There may be other cities with high job density.

No shi*, its where I’m pulling my stats. Couple problems with this data:

1) it’s from 2014. We certainly haven’t added any jobs since 2014

2) What is the point that two counties added together have more than one county? ok, yes, math works. Is there a 7×7 section in either county that contains the same amount of jobs in SF?

3) How is it possible that SF county has less workers than jobs. Workers should =jobs

Also, San Mateo can Contra Costa combined have more jobs than San Francisco. I gave you a link to the census so you can look and see for yourself.

Looking at the number of workers, there are 907,080 in Santa Clara County, 656,880 in Alameda County, and 610,880 in San Francisco County. The other 6 Bay Area Counties combined have over 1 million workers. San Francisco has less than 20% of all Bay Area workers.

cherry picking. There are more jobs in San Francisco county than in Marin county, contra costa, San Mateo county, alameda county

If they are made up stats it is the Census Bureau making them up.

http://onthemap.ces.census.gov/

because the valley looks anything like san francisco…

Only aging white baby boomers use the term “bamboozled”

Sorry, these are made up stats.

Bingo. This is 100% correct.

Build, baby, Build!

We need ALL the housing we can possibly get. Anyone who stands in the way is an idiot.

“I have already made this paper too long, for which I must crave pardon, not having now time to make it shorter.”

-Benjamin Franklin

I’m really in the middle on this, but I think this report is great. I skimmed it. I do think that every new building should have the toilets be recycled water in them with filters and all should have solar on their roofs.

I agree that our regional governance boards are extremely important, and I am thankful that Zelda covers it.

However, the article contains a lot of pejorative descriptions to dance around the issue of growth without saying exactly what she thinks is wrong with it: “pushes massive growth,” “their positions on Plan Bay Area’s gigantic growth forecasts,” “all accept Plan Bay Area’s growth-to-the-max premise,” “the massive growth,” “the growth autocracy.” What is unclear in the article is what exactly Zelda thinks is incorrect about the growth allocations.

• Does Zelda think the population and job growth projections themselves are incorrect? If so, what exactly does she think they estimated or modeled incorrectly?

• Or does she think the population growth projections are accurate, but want the children and less fortunate of the Bay Area to be displaced instead of building homes for them?

• Or does she think that the growth should be allocated more evenly to the suburbs rather than the transit-rich PDAs?

• Or does she think we should sprawl beyond the Urban Growth Boundaries?

It’s easy to be vaguely angry, but it’s harder to make a coherent specific criticism.

As for the supposedly sinister motives of the decision makers of ABAG and MTC, I think ABAG president Julie Pierce summed it up best in concluding the Nov 17th meeting:

“An estimated one third of people who are homeless have mental illness, according to the Mental Health Association of San Francisco. Depression is the most common disorder.

It’s important to note that while many people become homeless because of mental illness, the actual experience of being homeless can cause and exacerbate mental illness. Studies show that even living on the street for one week is traumatic and has negative affects on both the body and mind.

What’s more, living on the street increases a person’s chances of being a victim of rape and hate crimes, which also negatively impact one’s mental state.”

http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Questions-about-San-Francisco-s-homeless-answered-8323297.php

From what I have read most of them are chronically homeless with mental or substance abuse problems; not those who are down on their luck. Lowering the price of housing would probably have no effect.

The survey of the homeless may be true, but the fact that someone was living in SF when they became homeless is not relevant.. Where did they live before moving to SF. It is not unusual for someone moving to SF only to find they can’t afford it. Just because someone chose to move to SF obligates us to support them?

I would guess that most low-wage workers have roommates or employed spouses. That has been true for 50 years. Also the average commute of those restaurant workers time was really low.

Someone who used to have a job and a home, and now is living in a tent under a highway with no hope of finding work again because they are now stuck in the poverty trap.

Wait, you trust the Chronicle’s survey of restaurant workers, but not its survey of people’s hometowns?

The survey you referenced summarized the results as the lowest paying restaurant jobs couldn’t afford to commute, and thus share rooms in order to make ends meet. Which makes sense, considering that the only listings on craigslist that a minimum wage worker can afford is sharing a SRO room with 4 people for $650/month each.

http://www.sfchronicle.com/restaurants/article/How-far-do-the-Mission-District-s-restaurant-7947623.php

Just how is anyone “harmed?”

There is an abundance of service jobs because of gentrification. The number of food service and retail jobs have significantly increased on neighborhood commercial streets where there has been gentrification. Gentrification may have slowed the out migration of Latinos in the Mission.

There are newspaper articles that are identical to the one you cite in every Bay Area newspaper. It this same complaint from Santa Rosa to San Jose: we can’t find restaurant workers because of the cost of living. The problem is Bay Area wide not unique to San Francisco. It is related more to the low unemployment rate than to housing costs. In Healdsburg, a high-end restaurant solved the problem by substantially increasing wages. SF restaurants will also need to do the same.

From what I can tell most SF restaurant workers live in SF. The Chronicle did a survey of workers in the Valencia Street restaurants. 64% lived in the City.

I am a property owner, I want to see housing prices fall because they are harming my family, friends, neighbors, co-workers, etc. How selfish do you have to be to want to harm everyone you hold dear just to make another million on top of the million you already made.

So far the best data we have is that the homeless in SF are predominantly from SF, if you have different data then please provide it. Just because you don’t accept the results of the survey doesn’t mean the opposite is true.

Working class leaving SF not for lack of jobs, but for lack of housing. There are an abundance of service level jobs, just no longer a place for those workers to live. Reposting this link because it is also relevant here: http://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/nevius/article/Low-wage-jobs-are-plentiful-in-S-F-but-where-6515053.php

“People making $50K do in fact live in the City.”

Probably in a rent-stabilized apartment. What happens if they’re evicted, or the building burns down, or they get divorced, or, or, or…?

“Moving out of the City is not a death sentence”

Many things that are bad and worth preventing are not death sentences. Something not being a death sentence is a low bar.

Picking and choosing when you want to support property rights now?

oh god…

People making $50K do in fact live in the City. I suspect many of them live in households with other wage earners, roommates or spouses. But it may be true that some will not be able to find anything they are willing to live in anywhere in the City. Moving out of the City is not a death sentence and often improves one’s standard of living.

Yes over the years high-skilled highly-paid jobs have replaced low-skilled low-wage jobs, and the upper middle class has been replacing the middle class. There are few working class (blue collar) jobs left in the City. And as the working class jobs left the City so did the working class. I am not sure much can be done to reverse that trend or should be done. What’s the alternative; urban decay?

If immigrants stop coming we who will pay for our pensions? Europe had a problem with low fertility and that was one reason they agreed to accept refugees. They may have gone too far, however.

I take those surveys with a grain of salt. They are mostly self-serving. They don’t differentiate between temporarily and chronically homeless. In any case, where they were living at the time they became homeless many not be relevant. Most moved to SF from someplace else in the first place. We can help them return.

I am not sure what the point is about rural areas. For most jobs living “close” to work is not a necessity but I am not clear how that is relevant. Most do live reasonably close to work.

Comments like this are unlikely to change anyone’s mind.

Who is the “we” that want to see housing prices fall? Not most property owners. Prices will fall when there is a downturn in the economy and unemployment is high. I would not like to see that.

I am not sure what you mean by “care” but who is responsible to care for someone who chose to move to SF? No one was forced to move here. There are government programs for those who are unable to care for themselves. I suppose for some who qualify for assistance we could help them relocate to someplace they can afford to live.

Over most of SF’s history people have moved out of the City because they cannot find desirable or suitable housing in the City they can afford. Most of my childhood friends and all my relatives left the City over the years and were happier for it. Moving out of the City is not a death sentence.

Granting individuals stronger property rights is social engineering now? k

Actually, the start of the housing crisis in SF can be directly tied to the enactment of strict height limits in San Francisco. Do you realize that you are the leftist version of the tea party?

all emotion no fact

First of all, 90% of people who are now homeless used to have a home in CA, and 71% used to have a home in SF:

http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Questions-about-San-Francisco-s-homeless-answered-8323297.php

And second of all, cities are today’s economics economic engines. Rural areas have not recovered from the depression, and show little likelihood of ever recovering. You speak as though living in SF is a luxury that you, for some reason, deserve to keep for yourself, but for many living close enough to work in SF is a necessity.

Of course not, but there is a requirement for SF to build if we want to see housing costs fall. If you don’t care about lowering the burden of housing costs then I guess you don’t really care about “excess people” either.

Most people living in tent cities moved to SF from someplace else. We can improve their quality of life by providing relocation assistance to someplace they can afford to live. Most who leave the City at all income levels improve their standard of living by leaving the City. That includes the wealthy.

People who make the minimum wage live all over the place including within the City. Of course that may mean those who live in the City may have less than desirable living conditions. I would guess most who make the minimum wage and live in the City are not the only wage earner in the household; they have employed roommates or an employed spouse.

A month or so ago, the Chronicle did a survey of Valencia Street restaurant workers. 64% lived in the City. For the average City worker 38% live in the City. Also, the higher paid restaurant workers were more likely to commute. It was the lower paid younger workers and immigrant workers who were more likely to live in the City.

What trend over time? For any trend one must compare SF to other Bay Area cities. SF is not unique and is often average. For those that live within 10 miles of work, SF is above average; a higher percent of SF workers live within 10 miles of work compared to workers in other Bay Area cities, some with more affordable housing.

I agree that one problem is job rich suburban cities that refuse to build housing is a problem that exacerbates the City’s housing “problems.” In fact, according to the State’s definition of housing crisis, Santa Clara, Alameda, and Contra Costa counties have a greater crisis than San Francisco. Let them build first

Higher wage workers are more likely to commute than lower-wage workers. However, that is probably due to our high percent of young adults and immigrants. One reason why lower-wage workers are moving out of the City or the Bay Area is that lower-wage jobs are moving out of the City. The percent of SF workers that live more than 50 miles from work is average compared to other Bay Area cities. There are many more service jobs outside of SF than in SF.

Basic economics misapplied cannot disprove what we witnessed.

I’m not talking about rights, I’m talking about the negative impact on our neighbors of not building housing. Most of the people currently living in tent cities used to have a home in SF. It is hard to argue that their “quality of life” has improved because you prefer “slow growth” over them having a home.

Even the most inexpensive housing in SF is too expensive on a service wage. You have to make a minimum of $35/hr to live anywhere in SF unless you lucked into rent control years ago. Where do you think the people making minimum wage are living?

– http://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/nevius/article/Low-wage-jobs-are-plentiful-in-S-F-but-where-6515053.php

– https://ww2.kqed.org/news/2015/03/28/long-commute-to-silicon-valley-increasingly-the-norm-for-many/

Equal non-privileged housing will never exist. It’s a mirage, not a goal post. Sounds dangerously close to social engineering.

I have no objection to more building but I do object to rezoning that negatively impacts our quality of life. Your idea of slow growth over time, allowing for those here to adjust and for the infrastructure to adapt, makes sense. I would start with increasing the height limit along commercial streets.

People moved here voluntarily and leaving the City is not a death sentence. People are free to come and free to go. No one was forced to move to San Francisco. It is not a violation of anyone’s rights if they can’t afford to live in the City. No one has a right to live in SF.

Most workers, including servers, live within a reasonable distance from work. In fact a higher percent of SF workers live with in 10 miles of work compared to workers in many other Bay Area cities with more affordable housing. Higher paid workers are more likely to commute than lower paid workers.

No one is going to commute 3 hours for a low-paying job. More than 80% of the jobs in the Bay Area are not in SF. 15% of SF workers live more than 50 miles from work. That is average compared to other Bay Area cities and lower than some more affordable cities: For Concord it is 17% of workers that commute more than 50 miles, Hayward 17%, and Vacaville 20%.

The Mission is a trivial counterexample to the idea that rich and working class people are not competing for the same housing, but 2016 you have competition from the wealthy all the way out to the Excelsior and the Avenues, as you can tell from price increases over even the last four years.

That’s just a snapshot though, you also need to look at the trend over time. You also have to consider the income distribution of those commuters and what jobs they’re going to. The crazy distribution of high paying jobs in the Bay Area and the fact that the job-rich suburbs also refuse to build housing are both problems, but they do not address the problem of lower income workers being driven to the edges of BART or out of the Bay entirely.

Most commuters live close in. Oakland has 5.6% or 34,282 of SF commuters; Daly City 21K and So. SF 10K or 1.7%. San Leandro 0.9%, Concord 0.9%, Hayward 0.8% and Antioch 0.6%.

I suspect you purchased your house a while ago if you think that the argument here is people making $50K are pissed that that can’t afford a mansion in SF. People making $50K can’t afford to live anywhere in SF when the “least desirable” neighborhood has a median rent of $2,000 requiring a minimum income of $72K!

Pretending the people don’t exist is the most inhumane thing we could do as a city.

They are our neighbors living on the street because we refuse to build them a roof, our servers commuting 3 hours to provide us our “quality of life”, our friends living in states denying their rights who can’t move here because of housing prices you want to prop up.

And all it takes to house them all is building Paris sized buildings in 0.3% of our city per year! It doesn’t take a Tokyo, it just means that in 100 years, 30% of our city is more like Paris than like Lafayette. Can we agree that becoming a little more like Paris is worth saving the lives and livelihoods of our neighbors?

They came voluntarily and will leave voluntarily if they can’t find a place to live. There is no requirement that SF build to accommodate them.

Well unless you’re planning on loading up all these excess people into box cars and shipping them off to the gas chambers you’re kind of stuck with them Don…

“The Wall just got 10 feet higher!” -Zelda Bronstein

Who’s weighing anything? I’m talking about unequal privileges verging on feudalism, not “contributions” whatever that means

“We will not be the same city in 20 years if we do not build what we need”

We will not be the same city in 5 years if we build as much as you want.

Wouldn’t the evaluation of other lifestyles and their contributions to society weighed against Smart Growth, fit the eugenics banner?

Yes people who make more money can outbid those who make less money. But the wealthy are not necessarily competing for the same housing as the less wealthy. In any case, if you want to live in the City you often need to accept less space or accept living in a less desirable neighborhood. That is true for all income levels. And that has been true for many decades.

The premise was that if we build enough housing then everyone who wants to can live here and not commute. The is no evidence that more housing will mean less commuting.

There are cities in the Bay Area where there is enough housing for people who work in those cities but a higher percent who work in those cities commute compared to SF. For example, 85% of workers in Concord commute compared to 62% of SF workers who commute. Concord has more than enough housing for its workers but more commute.

The number that commute in versus out was not the issue. But SPUR was not far off. 379,151 come into SF to work, 156,775 leave SF for work, and 231,620 work and live in SF. The number that leave the City for work increases every year; the percent of reverse commuters has increased.

In John Muir’s time, population control was known by a much prettier name: eugenics.

Zelda, do please tell us more about how white baby boomer homeowners should decide who gets to live here.

Hey so about that wall…

I mean, obviously if you live in the city, especially a wealthy/hip neighborhood, your neighbors are going to be enriched for reverse commuters; traditional commuters live in places like San Leandro and Concord and Hayward and Antioch…

Believe it or not, most people in San Francisco want the “forced growth” you speak of, despite your reactionary conservatism.

This is what the article she posted to actually has to say about supply and demand:

“These findings provide further support for continuing the push to ease housing pressures by producing more housing at all levels of affordability throughout

strong-market regions. ”

We need to build more housing at all price levels, not just subsidized housing and not just market rate housing.

The problem is that by doing this you are screwing over the people who make $50K, because we will always be outbid by the people making twice or three times that (let alone even wealthier speculators and billionaires who want pieds-a-terres).

Where do you get these facts on commuters from? SPUR says that over 200,000 more people commute into San Francisco than commute out.

“San Francisco had no housing crisis until we lifted the height limits and allowed the real estate values to sky rocket” – I don’t think you have a grasp of basic economics.

A prescription for turning the City and County of San Francisco into a facsimile copy of the San Fernando Valley, that’s what this is.

LOL, so how do you *really* feel about Plan Bay Area?

I don’t believe the forecasts. When is the last time an urban planner made an accurate forecast? There are far too many variables to say what the population will be in 2040.

Worldwide the rate of population growth is slowing and should level off by 2040 or 2050 and then start to decline. Our population increase is mostly due to immigration. If immigrants stop coming we would start to see a population decrease.

The Plan Bay Area update is drastically underscaled — we should be planning for at least twice as much projected growth.

This all explains so much, and helps answer questions I’ve had.

Find the public funds and cut them off.

“They don’t explain why building all the new housing envisioned by updated Plan Bay Area 2040 would help people, especially poor people, who can’t get into the current housing market find shelter. Presumably they believe in the supply and demand argument, which has been repeatedly debunked (here and here).”

We’ve been down this road before. You ended up saying:

“S&D theory says meeting demand would lower the prices. It has nothing to say about matters outside of price. It can’t answer–indeed, it can’t even imagine–the questions I posed to whateversville. In that respect, it doesn’t apply. Of course, if all you care about is price, then S&D works just fine.”

What changed your mind, since then?

“If they have a different theory, I’d be glad to hear it.”

From 2009-2015, San Francisco added 123,000 jobs, 50,000 residents, and 12,000 housing units. Last year, the entire Bay Area added 133,000 jobs and 16,000 units of housing.

The “theory” is that 133,000 is a lot higher than 16,000.

Posts like yours are puzzlers. I know you live in the City – I think it’s time you explored it better.

Until pop.

There is a limit to what people are able to and willing to pay. But there is nothing wrong with those making $100K living in the City. We should continue to build less than the demand. We don’t need to satisfy the demand.

I actually support ‘growing’ San Francisco’s population to about 1.5 million. But increasing the density in the already congested areas is ridiculous. There are so many opportunities for building new neighborhoods – for example, look at the Alemany corridor. It is ripe for redevelopment and higher density. Ditto for other parts of the city including major streets in the Richmond and Sunset. I’m not talking about 30 floor buildings, just increasing the high limit to 6 or 9 floors on major streets.

Unless cars are completely banned (which is fine with me)in most of the Priority Development Areas listed above, public transportation will never work well, and sometimes not function at all.

Also, I agree with Zelda – unless there is robust planning and investment in services and infrastructure ahead of development, I will strongly oppose it.

Enough is enough. Do it right or don’t even think about asking.

St. Francis Wood is nearly as leafy and is more affordable than Palo Alto. I think around 7,000 who live is SF commute to Palo Alto for work while around 1,000 who live in Palo Alto commute to SF for work.

We already are Monaco and all the housing in the world won’t change that.

SF has fewer commuters (percent who commute to SF for work) than all other Bay Area cities with the exception of San Jose. Over 80% of Bay Area jobs are not in SF. In my neighborhood, nearly half of all workers who live there reverse commute; their jobs are not in SF.

Some would argue we have a too many people crisis not a housing crisis and we don’t need more growth. I could care less about the carbon footprint. Zoning helps to maintain our quality of life. I don’t want SF to become another Tokyo.

There are two options before you:

–Zelda’s plan. Continue to build far less new supply than we need to satisfy demand. Continue to see prices skyrocket year after year and anyone making less than $100K priced out of the city.

–Plan Bay Area. Make some radical changes to how we plan/approve/build in the city and build enough to meet demand. Prices will level off and when the next recession hits, demand will go down and prices will go down.

Everything else is just chipping away at the edges. I already own, so go ahead and fight for Zelda’s plan. If you thought $1000 psf was bad, just wait until we hit $2000 psf. That’s the only possible outcome of Zelda’s plan.

If you want to live in a leafy suburb, move to Palo Alto.

San Francisco desperately needs more housing. We will not be the same city in 20 years if we do not build what we need: we will be Monaco. The environment demands that we build enough housing so that everyone who wants can live here and not commute in from the suburbs.

Couldn’t disagree more with all of your points, disco. Dense cities are green cities. San Francisco had no housing crisis until we lifted the height limits and allowed the real estate values to sky rocket. If you want to change the supply and demand problem, you can quit advertising and marketing efforts to grow the population. If you want to live in a dense environment in a small box, move to New York or Toykyo.

Zelda has outdone herself with this one. If this doesn’t grab the public’s attention, nothing will. A growing disgust with forced growth and constant change brought to us by the Plan Bay Area has united the most unlikely of allies in our efforts to stop the too fast too soon changes being crammed down our throats.

Not surprised to hear that incumbents where removed from office. The only way citizens can revolt against city policies and priorities they detest is to remove the politicians backing them.

Mayor Ed Lee announced that he will be ignoring the wishes of the voters who passed props E, J, V and W almost immediately after the election. Even though voters supported street tree maintenance, health programs, affordable housing and free City College, that money will be going into the general fund, just as we predicted. The voters were bamboozled in less than a week this time. Will they buy the lipstick on the pig again?

This power play unfolding dwarfs the typical SF scrimmages. The wizard-behind-the-curtain, Mr Heminger, is pulling the strings almost unilaterally, and imposing a corporate/dictated vision of a regionalized megalopolis. Counties and Cities are obstacles, to be slowly led into redundancy. The infrastructure shortages we currently suffer from will seem benign if the mandated population explosion is carried forward. Lacking consensus, insurrection will inevitably be involved.

Zelda, it’s people like you who have brought us to this mess of a housing crisis. Your priority seems to be your own personal quality of life, ie being able to park wherever you want and not having to share the bay area with too many people.

A couple of things:

1. Without growth we cannot solve our housing crisis. As long as demand outstrips supply we will always be fighting over a what little housing is available. Efforts to create equity will only create a lottery with winners and losers.

2. Dense cities are green cities. Here in the Bay Area we are relatively low density and we have a pretty high transportation related carbon footprint. We could do with some extra density.

3. San Francisco was built out organically, without zoning. Excessive control and consensus will not necessarily result in a better city (and there is a fair amount of evidence to the contrary).

4. The city of Tokyo builds 75% more housing annually than the entire state of California. That’s 5 times as many homes per capita in a city with no remaining land. How do they do it? Removal of local control, prompted by the epic housing crisis of the late 80s.

I am with you. I stopped reading a quarter of the way through. I may get back to it later if I have time.

Just taking a peek to see if is this was one of Zelda’s trademarked wall-of-text articles…

I’ll be posting my comment sometime early next year when I’ve finished reading it.