With great fanfare PBS is airing a 10-part series about the Vietnam War. Critics charge that under the guise of being even handed, series producers Ken Burns and Lynn Novick say the US and Vietnam share equal blame for the war. Foreign correspondent Reese Erlich offers a different historical perspective.

October marks the 50th anniversary of Stop the Draft Week, the largest militant anti-Vietnam War demonstration up to that time. Ten thousand people jammed into the streets of downtown Oakland to shutdown the federal draft induction center.

Demonstration organizers, who became known as the Oakland 7, faced an 11-week conspiracy trial. In a major victory for the anti-war movement, a jury acquitted them of all charges.

Erlich was one of the Oakland 7.

In October of 1967, the U.S. war effort in Vietnam was failing. In just a few months, Vietnamese rebels launched the Tet Offensive, a political defeat that proved to be a turning point in the US war.

Throughout 1967 President Lyndon Johnson sent more troops to South Vietnam, and that required bigger draft calls. The sons of the very rich and well connected always avoided the draft. Donald Trump received a medical deferment due to “bone spurs” in his heels. They didn’t prevent him from a lifetime of skiing, however.

George W. Bush joined the National Guard through his father’s connections and then went missing from his unit for months at a time. Dick Cheney enjoyed a series of student draft deferments. When he was reclassified as draft eligible, he suddenly became a father and thus avoided service. These chicken hawks later became staunch supporters for unbridled wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Meanwhile African-American, Latino, and working-class men of all nationalities were drafted and shipped to Vietnam in ever larger numbers. Middle income students and married men, who had been exempt, gradually found they were reclassified. Anger at the war was growing. Black Power and civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, came out against the war and the draft.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

Stokely Carmichael, then leader of the Student Non Violent Coordinating Committee, popularized the slogans, “Hell No, We Won’t Go” and “No Vietnamese Ever Called Me Nigger.”

In 1967 an old buddy of mine, Steve Hamilton, and former Stanford student body president Dave Harris organized an anti-draft group called The Resistance. Draft age men pledged to refuse the draft, and many burned their draft cards. The Resistance mostly appealed to students and middle-income whites. But it had a powerful impact. The flames of burning draft cards lit a fire under the Johnson White House.

During the summer of 1967, some 30 Bay Area anti-draft organizers came together at a former Greek Orthodox church in the San Francisco Mission District to plan a massive demonstration. We called it Stop the Draft Week (STDW) and pledged to shut down the Oakland Induction Center from October 16-20.

We visited every anti-war group, union hall and church rectory that we could find. We plastered the Bay Area with leaflets, posters and buttons. We reached out to the growing counter culture movement. The Summer of Love was in full swing in San Francisco. As men’s hair got longer, women’s skirts got shorter.

We didn’t consider ourselves hippies, but the anti-war and counterculture movements were intertwined. Both groups used drugs, listened to rock, dressed unconventionally and engaged in the kind of sex that outraged our parents. But hippies tended to protest society by “dropping out.” We wanted them to “drop in” to the anti-war movement.

We also sought to broaden the anti-war movement by including workers and allying with black, Latino, and Asian activists. Dave Harris and his pacifist allies believed they could do that with an appeal to conscience and traditional, nonviolent tactics.

Others of us argued that working class youth were turned off by traditional pacifism. It was time that anti-war demonstrators become more militant and defend ourselves against police attack.

Our call for militant action was hugely controversial. Of course local politicians, university administrators and business people were opposed. But even most leaders of the mainstream peace movement were hesitant. Our rejection of non-violent tactics ran against the grain of protests at that time. Few leaders and no traditional peace groups endorsed STDW.

But we picked up grassroots support. I still remember walking the streets of Berkeley in early October and seeing scores of houses displaying Stop the Draft Week posters in their windows.

Our timing was spot on. “Our political antennae picked up something out there,” Oakland 7 member Terry Cannon told me years later.

The fateful week finally arrived. On Monday, Oct. 16, police arrested 123 people in a non-violent sit-in front of the Induction Center, among them folk singer Joan Baez, pacifist leader Ira Sandperl, and Dave Harris. A thousand others showed support by picketing.

On Tuesday 6,000 of us milled about in front of the Induction Center, some wearing hard hats and carrying shields. Others sat down in front of the doors.

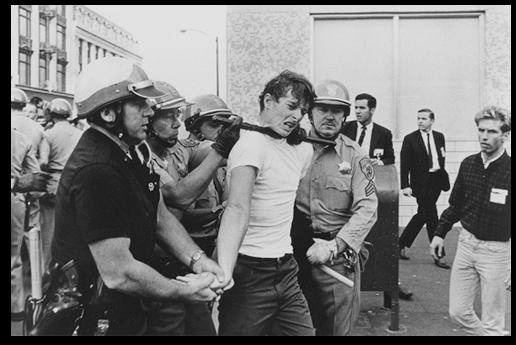

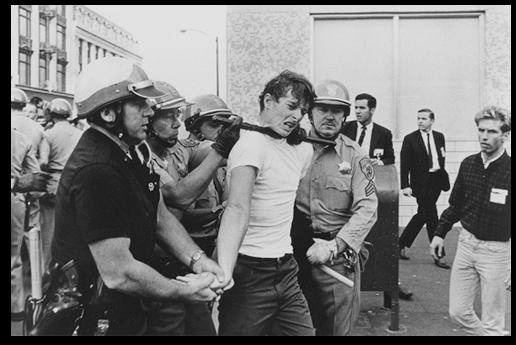

At 7am, police in riot gear formed a wedge 10 cops deep. They had no intention of making arrests; they were ready to bust heads. As the San Francisco Chronicle reported, “Police surged down the street, their hard wooden sticks mechanically flailing up and down, like peasants mowing down wheat.”

Dozens of TV, newspaper and radio reporters were viciously beaten. For the first time during a protest, local police used a liquid tear gas called Mace, spraying it into the eyes of demonstrators and reporters alike.

The police managed to clear the streets, and the army buses reached the Induction Center. But it was a huge political defeat for city officials. Peace and civil liberties organizations denounced the police violence. The mainstream media got a federal court injunction against further police attacks.

For the rest of the week, the police backed off. By Friday 10,000 demonstrators clogged the streets of downtown Oakland and closed the Induction Center for much of the day. Stop the Draft Week ushered in a new era of activism around the country.

“We raised the stakes,” recalled Frank Bardacke, another of the Oakland 7. “They could see the disruption that would happen domestically if the war continued.”

In retrospect I think we made a lot of mistakes. We were full of bravado and boasted of fighting with the pigs. Like many of today’s young anarchists, we focused on tactics as a test of our revolutionary mettle.

I learned from STDW that tactics don’t determine the success or failure of a movement. Strategy does. Strategy defines who are our friends and enemies. Tactics flow from that. In the context of 1967 anger at the war, militant tactics made sense and helped broaden the movement.

For many years blue collar workers would tell me that their first experience with the anti-war movement was when they came to Oakland to check out STDW. Conditions had changed and the anti-war sentiment extended way beyond college campuses.

Future mass mobilizations featured progressive unions. Black, Asian, and Latino groups also demonstrated in the hundreds of thousands against the war and draft. We became part of a much wider, militant movement.

For a time, the revolutionary and pacifist wings of the movement ruptured–a reflection of the short sightedness of both sides. We could have disagreed on tactics but still found ways to work together.

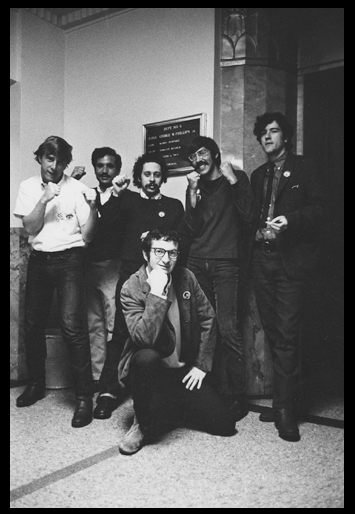

In 1967 the federal government, fearing more protests, refused to prosecute Stop the Draft Week leaders. So in January 1968, local District Attorney Frank Coakley proceeded on his own. Coakley was an infamous right-winger and a strong supporter of then Governor Ronald Reagan. He charged seven of us with conspiracy to commit misdemeanors, which was a felony. The Oakland 7 were Frank Bardacke, Terry Canon, Reese Erlich, Steve Hamilton, Bob Mandel, Jeff Segal, and Mike Smith.

The DA had a hard time deciding who to indict. Most of us were not well known, and dozens of people had helped plan the demonstrations. A number of women played prominent organizing roles, but the DA was reluctant to charge them, fearing it would provoke sympathy for the protestors.

Coakley told the Oakland Tribune, “Technically a hundred or even a thousand of the demonstrators could have been indicted for their action. But we simply don’t have enough courts so we have to take the most militant leaders.”

The nature of the charges confused a lot of people and ultimately the jurors. The conspiracy to commit misdemeanors law had never been used against protest leaders before. Most people couldn’t understand how organizing a demonstration in which protestors committed misdemeanors could suddenly become a felony, punishable by a maximum of three years in state prison.

The Oakland 7 trial began in January 1969. We organized for the trial just as we had for Stop the Draft Week. Mass demonstrations and picket lines erupted in front of the courthouse in downtown Oakland. Our attorneys—Charles Garry, Malcolm Burnstein and Richard Hodge—presented a spirited defense of the anti-war movement as part of our defense. The trial lasted 11 weeks.

The turning point came when prosecutor Lowell Jensen tried to present audiotape excerpts from the five-hour Stop the Draft Week rally at UC Berkeley. Judge George Phillips ruled that Jensen had to play the entire tape not simply the excerpts he considered incriminating.

The tape was Berkeley in all its wacky diversity. Some speakers supported militant tactics, others opposed them; some called on God for support, others invoked Karl Marx. Having listened to the tape, the jury understood that no conspirators had organized the demonstration. It had been a popular event full of passion and contradictions. Jensen, who eventually became a federal judge in Oakland, later told me the tape “was a disaster for the prosecution.”

On March 28, 1969, after only three days of deliberations, the jury returned not-guilty verdicts for all defendants. The jury—a cross section of urban workers and professionals from Alameda County suburbs—ruled our protest free speech not conspiracy. One juror said, “I wonder what the prosecution would have made of the Boston Tea Party?”

The Oakland 7 were never a politically homogenous group. After the trial we went our separate ways. But all of us continued organizing against the system in one fashion or another. After 50 years we remain committed to peace, justice and losing about 10 pounds.

Journalist and book author Reese Erlich excerpted this article from his memoir-in-progress. The Oakland 7 will be holding a 50th anniversary party Oct. 21. For more info, email him at ReeseErlich2@hotmail.com

Where are the Oakland 7 today?

Frank Bardacke, 75, has lived in Watsonville since 1974. He taught for 25 years at the local Adult School and now teaches a class in U.S. history during the Fall semesters at Cal State Monterey Bay. He also wrote the highly acclaimed book Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers.

Terry Cannon, 77, is an author living in Los Angeles. He is completing A Child Went Forth: Making Sense of Race and Racism, a book that is both memoir and history. He investigates the invention of the idea of race and the continuation of racism, as seen in part through his personal experiences confronting both.

Reese Erlich, 70, is a freelance print and broadcast journalist in Oakland. He taught journalism for 10 years at Bay Area universities and was vice president of the faculty union at Cal State University East Bay. He has authored five books on foreign affairs and won a Peabody for his coverage of Asians in America. He has reported from 88 countries.

Steve Hamilton organized factory workers in Richmond and later became a therapist San Francisco. He came out as gay in 1980 and fought for gay rights. Hamilton died from a heart attack in 2009 at the age of 64.

Bob Mandel, 73, is an adult education ESL teacher and union activist. Since 1998 Mandel has been active in the campaign to free political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal. From 2001-11 he was elected to the Oakland Education Association Executive board. Most recently he participated in a three year successful effort to organize a union in the Richmond/West Contra Costa Adult Ed system.

Jeff Segal, 75, refused the draft and spent 27 months in a federal prison. From 1980-2008 he was a staff attorney with the Legal Aid Society in Louisville, KY. He remains active in the National Organization of Legal Service Workers affiliated with UAW Local 2320. He is on the steering committee of the National Lawyers Guild Military Law Task Force.

Mike Smith, 76, is a former nurse and retired union organizer living in Sonoma County, California. He remains active in the northern California peace movement. He is part of the local rapid response network to ICE immigration raids. Smith served two terms on both the Sonoma valley hospital board and the Santa Rosa community college board of trustees.

Great historical view of a movement that started 50 years ago and put a stop to a brutal war. It feels like we are waiting for the sleeping giant to wake up and take action again, but, so far nothing is happening.