The weekly tenant meetings of the residents of Midtown Park Apartments at the corner of Geary and Divisadero always begin and end with a prayer. For the past year, the meetings have focused on a historic project: the largest rent strike San Francisco has seen in nearly 40 years.

The regular meetings are held at the New Liberation Presbyterian Church, where many tenants are members—the group has been locked out of their apartment complex’s community room by property management.

“Oh Heavenly Father, help us and guide us in our times of struggle,” says Midtown resident Manzell Clay, leading the evening’s prayer one Thursday night. A cross-section of working class San Francisco greets each other at the meetings with hugs and inquire about family members.

Father and son Cesar and Arthur Raquel are present at nearly every tenants meeting and Cesar films every event—whether a meeting, a protest or a community BBQ. He’s documenting the tenants’ struggle for his wife, who is bedridden in their apartment but is eager to learn of new developments. The family emigrated from the Philippines and moved to Midtown in 1983.

“My wife is so worried,” Cesar says, “But I tell her ‘Don’t worry we’re not in the Philippines anymore, where if you don’t come from a rich family or are friends with a politician you are ignored. We’re in San Francisco now.’”

The controversy at Midtown has roots in the city’s failed Redevelopment policies of the 1960s and 1970s, when much of the Western Addition was bulldozed for “slum clearance” and thousands of Black families and businesses were displaced, never to return.

For many of the tenants, who remember the Redevelopment era or have parents who do, history is inescapable: It’s as if the tenants, 50 years later, are still fighting the political legacy of an agency that no longer exists but that once, under the direction of City Hall, left deep scars in the Western Addition.

The current ongoing rent strike and heated protests are also the result of many years of what at best can be called bad communications by city officials and a series of private property managers who told the tenants they would someday have the opportunity to own their units and that in the meantime, their rents were subject to the city’s rent control laws.

Two years ago, the tenants were abruptly informed that neither outcome is possible– that they will never have ownership opportunities and that rent control doesn’t apply to them.

The fact that the rent-control law may, in fact, not apply to Midtown and that ownership models for the complex at this point in time are complicated and expensive doesn’t change the reality on the ground: For years, the tenants were told a different story.

For decades, Midtown was managed by a tenant-elected board that set its own rules and, former members agree, allowed rents to stay so low that revenue didn’t match expenses and maintenance problems piled up.

When Mercy Housing took over, the management group shifted Midtown from the model it had followed since shortly after it was built—essentially, the model of a tenant-managed rent-controlled building – to a standard nonprofit housing model, in which rents are tied to annual mandatory income certifications.

Mercy Housing also introduced an affordable housing lease, which contains provisions very different from what the tenants, who wrote their own rules and bylaws, had been living under since the 1960s. Failure to sign the lease can qualify a tenant for eviction.

Mercy Housing President Doug Shoemaker says he now agrees that his operation should have been “more sensitive to the building’s history.” He told us he wants to avoid evictions, and so far, nobody has been thrown out for not signing the lease.

Western Addition Supervisor London Breed told us that “the tenants have been lied to for years. The city really messed this up,” but nonetheless does not support the tenants’ rent strike, nor their aspiration for equity ownership.

Dean Preston, the director of a state-wide organization for tenant’s rights who is running for supervisor in the district, told us that the city is still doing the wrong thing: “They could have just recognized that this was a historically rent-controlled property and tried to keep that model,” he said.

So now tenants, mostly African American, many with families who have grown up at Midtown, some who have been there since the Redevelopment era, are mounting vocal protests, taking on the administration of Mayor Ed Lee and a giant nonprofit housing manager that has tight connections to City Hall.

The city – which owns the property – now considers Midtown to be part of the affordable-housing infrastructure, most of which is managed by nonprofits like Mercy Housing that use federal money earmarked for low-income tenants. It’s illegal for that money to go to a project where some tenants make more money than federal guidelines allow.

And with the city desperately in need of new sources of permanently affordable housing, Midtown is immensely valuable.

Midtown tenant leaders don’t see it that way at all. While many are on fixed incomes or are working-class, others are not – and see no reason why they should have to pay higher rent—mainly because many original residents were already displaced once by the city and because they were promised ownership.

“We are not an affordable housing project,” tenant leader Phyllis Bowie told us.

Pat Smith, who has lived at Midtown since 1970 and has raised eight disabled foster children there, notes: “We are not public housing, we are not HUD and we are not Section 8. We have never been. And that’s what they’re trying to make it look like now.”

Midtown isn’t public housing, and it’s been operating under a unique model, but it’s still public property – and nobody can seriously suggest that it will be anything in the future other than some sort of affordable housing. Of course, the city’s ownership is part of the problem: For decades, the city was an absentee landlord, either willfully or negligently ignoring maintenance issues and paying little attention to how its property was being run — and then acted precipitously when things reached a crisis point.

RENT STRIKE

Of the 130 households at Midtown, 65 families have been on rent strike for nine months. Striking tenants have refused to pay the increased rent that came with the new lease since August 1, 2015. Some tenants, whose rent is actually decreasing under the terms of the new lease, are striking out of solidarity with their neighbors.

Striking tenants argue that those who did sign the new lease and have already paid the increased rent have only done so out of duress. Some tenants who were interviewed but who declined to be named gave explanations for signing the new lease and rental agreement.

“They told me my rent would be raised to market rate if I didn’t sign,” said one tenant. Another responded, “I didn’t know what to do. I thought I would be evicted.”

So far, nobody has been evicted from Midtown.

This is the largest rent strike in San Francisco since the Ping Yuen North Rent Strike in Chinatown, in which 200 units – out of 434 – stopped paying rent from September 27, 1978 to November 18, 1978. The Ping Yuen residents had been fighting for months to improve the dangerous conditions created by a lack of security around the complex. It wasn’t until the murder of 17-year-old garment worker and Ping Yuen North resident Julia Wong on August 23, 1978 that the tenants’ furor coalesced into an organized rent strike.

Unlike the Chinatown rent strike, striking Midtown residents are only paying the old rent they paid under rent control—the rent that they believe to be fair—making it a partial rent strike. It is unique, however, in that it is entirely self-organized. Of the 139 households, all but 33 of them have had their rent raised. Some of the households who experienced rent decreases are striking out of solidarity with their neighbors by refusing to sign the new lease, as are those tenants whose rent is basically staying the same.

“It’s the principle of it,” says Bowie.

“It doesn’t affect me that much,” says Donald Griggs, whose rent increase was negligible. “But what about my neighbor? That’s my friend we’re talking about.”

REDEVELOPMENT WOES

The Midtown Park Apartments opened in 1968, 20 years after the Redevelopment Agency first designated the thriving, historically Black Fillmore District as “blighted” and therefore a prime candidate for its “Urban Renewal” agenda.

At the time of Redevelopment’s assessment, the Fillmore-Western Addition was the home of an established jazz district known internationally as the “Harlem of the West.” It was a neighborhood of Black-owned hotels, music venues, restaurants, businesses and homes, such as Jimbo’s Bop City restaurant and the Blue Mirror nightclub. Over the next 30 years, under two major phases of Redevelopment, the agency would use eminent domain to seize and demolish properties in the Fillmore-Western Addition until the neighborhood was barely recognizable.

One hundred and four square blocks of homes, small businesses, venues and churches were demolished. Some 2,500 of San Francisco’s famous Victorians were razed to the ground. Historians estimate that between 20,000 and 30,000 people were displaced.

The city promised residents of the Fillmore alternative housing (residents were given vouchers for replacement housing by the Redevelopment Agency) but for the most part, it was too little and far too late. With many of the demolished lots kept vacant by the Redevelopment Agency for as long as 20 years, many former residents had no choice but to move elsewhere.

By the time that most of the new affordable housing sites and public housing projects were built, much of the Fillmore’s long-term resident base had left for Bayview Hunter’s Point, Oakland and the greater Bay Area. According to a historical and geographical survey on the Western Addition and the Midtown Park Apartments conducted for Mercy Housing by planning firm Page & Turnbull, in one 23-square block area of the neighborhood, only three of the original residents ever returned.

Midtown Park Apartments was one of about 30 affordable housing developments built as a result of community pressure to provide relocation housing for residents who had lost their homes to Redevelopment. In some ways the apartments could not substitute for the single-family homes that many Black families had once owned. However, Midtown was considered a desirable new development—particularly because residents were told that if they bought into Midtown, they could work towards a future of housing stability again.

“Out of the disaster of Redevelopment that displaced African Americans from the Western Addition, Midtown was founded on economic empowerment for my community,” says Bowie, a 30-year Midtown resident and veteran Air Force captain.

Bowie’s mother was an organizer in the Black community in the 1960s, and worked with the Western Addition Community Organization, one of the main neighborhood groups that fought Redevelopment and community displacement.

Today, Midtown is a close-knit community of multi-generational Black residents and Asian, Latino, and Eastern European immigrants. Disabled veterans, fixed-income seniors and families with school-age children also live at Midtown. Nearly one-quarter of Midtown’s tenants have lived at the place since its opening in 1968. According to the survey on Midtown cited above: “It is known that many families have lived at Midtown Park for several decades and maintain a close community.”

The close community that makes Midtown so exceptional in San Francisco is not happenstance. Residents who essentially ran their own housing operation were able to fill the units at Midtown with children, relatives and community members.

Most affordable housing in San Francisco is allocated by lottery. At Midtown, it was allocated by a tenant board – so people who were part of extended families had an advantage over those with no connections. That is a big reason why the place is still largely African American. It’s also a model entirely at odds with the city’s longstanding policy of giving anyone who is eligible a shot at available housing.

Any current tenant will point out the notables who once called Midtown their home. “We have always had prominent people in the community living here,” says Pat Smith. The family members of Willie Mays lived at the apartments, as did Carlton B. Goodlett, the African American civil rights champion, doctor, and newspaper publisher for whom the street in front of City Hall is named.

What further sets Midtown apart from other housing is its unique nature as the only city-owned property in San Francisco that is not federally-subsidized public housing.

Like many Redevelopment Agency projects, Midtown started off with the government essentially giving land to a private developer. The developer, Barton-Western, then used public and private money to build the apartments. The development company initially advertised the units with the slogan “Own your Own,” promoting a scenario in which tenants would eventually have equity ownership in a co-operative.

But that turned out to be inaccurate– the developer quickly backtracked and told the residents that they were just renters.

In 1968, 35 of the 60 tenants who moved into the Midtown Park Apartments sued Barton-Western for false advertising. The tenants alleged that the company had initially hung “for sale” signs on the buildings then, without notice to the new residents, changed the signs to read “for rent.” After several years, the suit was dismissed with a settlement for the tenants.

Meanwhile, Barton Western went bankrupt.

That left the federal government, through the Department of Housing and Urban Development, holding the deed to the property. The city introduced plans to convert Midtown to short-term temporary housing for Redevelopment “relocates,” much to the dismay of existing tenants who believed that Midtown would be a source of stable housing.

At that point, several residents of Midtown petitioned the city to abandon their proposal for temporary housing and to allow the tenants to create a tenant board to manage the property themselves. The Board of Supervisors, led by Dianne Feinstein, approved. HUD turned Midtown over to the new tenants’ corporation, along with a $2.1 million mortgage, financed by a private bank.

Midtown then deeded the property back to the city, which gave the tenant corporation a long-term lease and the responsibility to pay back the mortgage.

Bob Love, a tenant at Midtown between 1968 and 1977, was one of the original residents who formed the tenant board, the Midtown Park Corporation. By the time that he arrived at Midtown, the promise of tenant ownership by Barton-Western was gone, but the lawsuit that the tenants won resulted in a settlement that allowed tenants to reinvest capital into Midtown.

“We were trying to create a community here,” recalls Love. “We did all of the applicant interviews ourselves. It didn’t matter if you were a single mother, or didn’t have the best credit, as long as you were a good fit for our community and could pay your rent.”

This kind of tenant self-management was unique in the nation and certainly, the West Coast.

“We started getting calls from all over the country, asking us, ‘How do you do tenant self-management?’ recalls Love. “We were really a model community in that respect.”

Under the terms of the lease, the Midtown Park Corporation would hire an outside property manager to handle rents, maintenance, security, and all of the other responsibilities involved in running a large residential apartment complex.

According to public records we’ve obtained, the lease stated that rents could only be increased with the approval of the Board of Supervisors. After 1979, when the city passed a rent-control law, property managers told the tenants that their rents were subject to the new law. Tenants have saved decades’ worth of lease documentation stating their rent was pursuant to rent control.

Rent control operates very differently from the rules that apply to traditional affordable housing. Nonprofits that develop and run affordable projects, using federal, state, and local public money, are required to make sure that their tenants are in fact low-income or moderate-income; the tenants applying for those units are required to demonstrate their income, and certify on a regular basis that they still meet the standard. In most cases, using a federal standard, tenants are asked to pay no more than 30 percent of their income for housing.

Rent controlled apartments carry no such requirements. A tenant who moved into a rent-controlled unit 20 years ago who later became successful enough to make a middle-class living keeps the same rights to a stable rent – much as a homeowner keeps the right to a stable mortgage and property taxes no matter how much their income increases over the years.

Rent control is the biggest and most important source of affordable housing for the working and middle class in San Francisco.

At the same time, rent control is limited: When a tenant leaves, the unit reverts to market rate. The city’s affordable housing buildings are affordable forever; when one tenant leaves, another who meets the eligibility criteria moves in and pays a maximum of 30 percent of family income.

After Mercy Housing took over, the tenants were told that the rent control law doesn’t actually apply to them. The Rent Board recently ruled that city-owned properties are exempt from the rent ordinance. The issue is now in court.

One of the greatest questions regarding the situation at Midtown is why the city, as landlord, didn’t address the rent-control issue earlier. City officials now say the project was in a state of financial crisis because the rents were too low – but tenant leaders tell us that when the tenant management board tried to raise those rents in past decades, they were told that wasn’t possible – because the complex was under rent control.

HOME OWNERSHIP

In the mid-1980s and 1990s Midtown tenants had numerous meetings with city officials, including then-mayor and now Senator Dianne Feinstein, to draft a plan for cooperative ownership for Midtown. Out of these meetings resulted a resolution to begin the co-op process once the mortgage on the property was paid off.

Turning Midtown into a co-operative would be more difficult than it was for the other housing co-operatives in the neighborhood – because it was built with public money, and owned by the city, there was no way the tenants could simply take ownership with the ability to flip their units for a profit. That would take the entire property out of the city’s affordable housing stock.

But there are plenty of models in which tenants have limited equity, with the ability to maintain stable ownership, but agree that their units can’t be sold at market rate. That’s what land trusts do, and this option is not without precedent in San Francisco.

Then-President of the Midtown Park Corporation Orice Johnson proposed that tenants take a proactive step towards co-ownership by contributing additional funds beyond rent towards completing payments on the property’s mortgage. It’s not clear whether she and others at the time were thinking about traditional equity ownership, with the right to sell for profit, and it’s not clear what the city’s position was. A resolution calling for Midtown to finally become a co-operative passed unanimously and was signed by then-Mayor Gavin Newsom.

The resolution was titled Approval of Guiding Principles for Determining the Future of Midtown Park Apartments: Resolution approving the principals that will guide the City and Midtown Park Apartments’ residents in formulating a long-term ownership structure and development plan for Midtown Park Apartments, a 140-unit residential development owned by the City and County of San Francisco.

The resolution recognized what it regarded as several unique aspects of Midtown, including its “racially and ethnically diverse” resident population. It also affirmed that the lease with the Midtown Park Corporation existed to ensure housing for its tenants with incomes ranging from “very low to moderate” and “empowers the Corporation’s Resident Board to oversee the operation of Midtown Park Apartments.”

The resolution went on to say that “MOH has recommended that the City’s ownership of Midtown Park Apartments be terminated as soon as a new ownership structure acceptable to both the City and the [Midtown Park] Corporation can be determined… MOH is committed to working with the tenants to complete the planning for a transfer of ownership and substantial rehabilitation of Midtown Park Apartments”

The resolution states very clearly that the input of the tenants was essential to any future planning process and developments.

Olson Lee, the current director of MOH, told us that his understanding of the situation is very different. “MOHCD wrote the principles as a way to demonstrate our commitment to working with the community to create a feasible, viable, development,” he said. “The ownership structure was determined to be financially infeasible unless rents or carry charges were raised to a level that would not be affordable to the vast majority of residents.”

But the tenants we’ve spoken with say they were never shown a study demonstrating that the co-op model wouldn’t work – or that a hybrid model, in which some residents would become owners and others remain renters, was infeasible.

One member of the Community Land Trust present during the talks with Midtown said, “I always thought that a mixed rental and ownership scheme would be perfect for Midtown. Long-time tenants invested in equity ownership could finally own, and renters who wanted to rent could continue to rent, providing a source of capital for the complex. From our perspective, ownership at Midtown was never infeasible.”

Meanwhile, Lee says, Midtown was running a deficit. Essential maintenance was delayed. The roofs leaked. “The city has spent over $4.8 million on emergency capital repairs over the last four years,” Lee said.

However, the city was the property owner. If a private owner –whatever the lease terms– allows housing to deteriorate to the point at which it’s unsafe, that owner is responsible. But the records we’ve reviewed show no indication that the city stepped in during most of the past 30 years to make sure its property was properly maintained.

MERCY TAKES OVER

In 2013, the John Stewart Company, which the tenant group had hired as the property manager, told the city that it was too expensive to get insurance for the property and that they no longer wanted the contract.

Two days before Christmas in December of 2013, tenants were told by MOH that the lease between the city and the Midtown Park Corporation was being terminated and the Midtown Park Corporation would effectively be stripped of its power. The following month, the city signed a month-to-month lease with Mercy Housing, a national Catholic affordable housing non-profit (the largest in the nation) headquartered in Denver, CO, with 35 other properties in San Francisco.

At a January, 2014 Board of Supervisors meeting, Breed announced that the new lease would have “no impact on resident leases.” That turned out to be wrong.

Mercy Housing immediately did what it always does as a property manager: It moved to put Midtown under the same rules as any other affordable housing project. But in this case, the lease included rules that the Midtown tenants—who had operated under tenant self-management for over 40 years—had never seen before, like restrictions on overnight visitors, new regulations for the use of common space – and most important, income certification.

Instead of the rent-control model, tenants would be required to prove their income, and pay 30 percent in rent. For all but 33 of the 139 tenant households, that meant a rent hike– in some cases, a fairly substantial rent hike (the largest was more than 300%) – which would be phased in over the next five years.

Shoemaker, the current head of Mercy Housing California, told us that in retrospect, he should have paid more attention to the history of Midtown. Imposing a traditional nonprofit contract on a property that operated for half a century with a very different model was, he said, “trying to put a square peg in a round hole.”

But Shoemaker said that it’s difficult to go back to the old model, since much of the money he’s trying to raise to pay for deferred maintenance and upgrades of the units comes from federal and state sources that have strings attached. You can’t spend that money unless the tenants who get the benefits are earning less than 60 percent of the average median income for the region, he said. And they have to prove it.

Preston told us that the city made a big mistake when it gave Mercy Housing the approval to impose a new lease structure.

“If the tenants thought they were under rent control, and that was the practice for all these years, the city should have stuck to that,” he said. That may have required more city subsidies for the maintenance, but as the landlord, the city should have been more attentive to maintenance needs over the years.

The maintenance issue remains another major question: If the apartments were falling down (and tenants tell us that the maintenance problems are overblown), why didn’t the city or Midtown’s property managers act on the problems years ago? Isn’t that what professional property managers are supposed to do?

And if that required rent increases for the tenants, why didn’t the Board of Supervisors, which had the legal authority to raise rents, do anything?

One long-time member of the Midtown Board told us that the board was focused on keeping rents low to prevent displacement. “Every time we talked about raising them, people would go running to the supervisors.” And the proposed rent increases would fail.

So as maintenance and deficits piled up, the tenant board, the private management companies – and the city – just kept on doing business as usual.

And the city as landlord was entirely missing in action as its own property deteriorated.

When the Mayor’s Office of Housing decided that the situation was an emergency, there was no traditional bidding process, no ability for competing property managers to make offers. Instead, the Mayor’s Office of Housing simply contacted Mercy Housing, which the tenants had hired to help with future development planning, and gave the organization an immediate contract. “It was reasonable to assume they were a likely entity to step in and manage the property,” Olson Lee said.

There were no bids, no Requests for Proposals (RFPs). Mercy wound up with the job because the Mayor’s Office thought that was the best fit.

Shoemaker is the former director of the Mayor’s Office of Housing. In that job, he gave Mercy Housing contracts to five properties in San Francisco in his last years as director. He was required to appeal to the San Francisco Ethics Commission in order to take his new position, which he assumed in 2011.

There is some indication that this sudden “emergency” was well known to MOH officials, who, records indicate, have been talking for years about turning Midtown into a traditional nonprofit model.

Emails obtained through the San Francisco Sunshine Ordinance show staff in the Mayor’s Office of Housing celebrating the termination of the lease with the tenants’ board.

One email from MOHCD staffer Joan McNamara to Barbara Gualco, the Director of Real Estate at Mercy Housing, says, “I’m now home eating a slice of Delassio’s chocolate cake that Pam bought me to celebrate our accomplishment! How groovy is that?”

Another email, dated one month later, reads:

“The Board fought hard and is continuing to fight this transition. However, anyone who looks at the books and practices of the current and previous board members and the state of the development will understand why we had to take this action.

“It took us nine years!”

In other words, the emergency that Olson Lee declared in 2014 wasn’t sudden or unexpected. The City had been moving to change the lease at Midtown since at least 2005 – without informing the tenants.

THE RIGHT PERCENT

Some tenants question whether 30 percent is the right amount of income to pay for rent, and they aren’t alone.

Amy Bayley, Regional Vice President of Community Planning at Mercy Housing justifies the model, saying, “It’s just the nationally recognized norm. You can look it up, just in terms of healthy living, healthy finances. It’s reasonable to expect that people would be paying about 30%…”

In fact, much of federally-subsidized housing requires that tenants pay no more than 30% of their income in rent, a figure that originated during the New Deal and was increased in the past 10-20 years despite a stagnation in wages.

But Midtown is not public housing, and the federal standards have always been a maximum, not a minimum.

Some major economists are now suggesting that the “30% of income” rule is arbitrary at best, and inequitable at worst. Recent articles in Fortune and Bloomberg magazines have called the 30% of income rule “arbitrary” and “nearly useless” and say that it does not reflect a variety of other factors. These economists argue that 30% of income going towards monthly rent is a reasonable percentage for a renter with a substantial annual income—but for very low to moderate-income tenants or retired seniors on a fixed income, 30% can be too high and has the potential to create a poverty trap. Any number of factors, including unexpected medical expenses, can push a tenant who is paying 30% of their income towards rent into debt.

In addition to the requirements for financial certification, the lease introduces stringent codes of conduct in a new set of “House Rules.” According to the lease, to wear shorts in or around the laundry room, sit or stand for too long in stairways and courtyards, or have visitors stay in apartments without a full month’s notice to property management, are all grounds for eviction or grounds for rent to be subject to increases to market-rate.

For residents who had lived under very different rules for decades –because they set their own rules — most of the new lease was unreasonable. And it’s understandable that people who remember Redevelopment, whose families were displaced by the city, don’t trust the Mayor’s Office of Housing or its contractor.

“When I signed my lease in 1995, I relied on the fact that a portion of my rent would be used to pay off the mortgage,” says Bowie, who experienced a 300% rent increase. “After we—the tenants—paid off the mortgage in 2007, we relied on the Board of Supervisors Resolution promising that ownership would be transferred from the City to Midtown residents, which as of today still has not happened,” Bowie says.

Former Supervisor of Midtown’s District Ross Mirkarimi remembers the situation well:

“[The Midtown tenants] did a magnificent job for over 30 years… The city as a landlord really is almost punishing them for their success. That’s how the city is treating them. I think this is such a step backwards, especially in the climate of how difficult housing is, and how pronounced the economic class divide and Black displacement is. I really wish in some ways that the city would just have left them alone and given them the support and resources they needed because they were doing such a good job on many levels.”

Feasibility studies dating as far back as the 1970s and 1980s discussed the option of terminating the lease with the tenants’ association but ultimately rejected it. Of all the possible outcomes, terminating the lease with the tenants would be most likely to result in what they noted as “public outrage.”

The rent increases and income certification are not the only complaint that tenants have. Tenants describe their grievances with Mercy Housing’s management of Midtown, complaints that they have directed towards Mercy’s Northern California offices as well as to Mercy CEO Jane Graf, based at Mercy Housing’s national headquarters in Denver. But tenants say they have yet to see any changes, or even a response. Residents have complained about management staff cutting locks to enter apartments without proper notice and entering private bedrooms during kitchen inspections. Tenants also complain about a lack of basic repairs that have been requested for over two years—for example, to fix broken awnings that result in water damage and mold inside the apartments.

Mercy has also reduced security hours, leaving tenants vulnerable after 3am when some tenants—many of them single women—return from night shifts. Recently, a fire alarm went off in one building at 4 am but could not be turned off because there was no security manager to direct the fire department. Instead, the fire department was forced to break down a door—for the third time this year—while senior tenants waited outside in the cold.

SENIOR TENANTS

One of the most immediate concerns is the number of seniors with limited mobility who are living in walk-up apartments. Midtown does not have elevators. Several seniors have been asking to move to ground-floor apartments – some of which are now being rented out to people displaced from housing projects throughout the city that are undergoing renovation.

The issue has become urgent now, as many Midtown residents of the same generation are aging in place and are now in a position to require ground-level accommodation.

Jose LaCrosby was a long-time Midtown tenant whom other tenants describe as “an absolute pillar of the Fillmore-Western Addition community.” La Crosby considered the first Black hair stylist of national renown—prior to moving to Midtown, he hosted Nina Simone, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, James Brown and other jazz and soul luminaries at his Victorian home on Fulton Street at a time when Black performers were barred from staying at San Francisco hotels.

For ten months following an injury, LaCrosby was essentially stranded at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center. His doctor would not give him dispensation to go home until he could move to a ground-floor apartment at Midtown, and his friends say Mercy Housing would not give him a ground-floor apartment without raising his rent to market rate.

On January 27th, 2016, tenants from Midtown attended a meeting with the senior staff of Mercy California (Shoemaker, Bayley, Gualco) and asked that immediate action be taken to bring LaCrosby—who had since entered Hospice Care at the VA hospital—home. Mercy staff responded that they were working on it. Two days later, on January 29th , 2016, tenants were informed that LaCrosby had died the VA.

Ramona Johnson expressed how upsetting LaCrosby’s death was for Midtown residents. “All he wanted was to die in his home,” she said. “That’s yet another tenant gone.”

Shoemaker told us that Mercy did offer “reasonable accommodations” to LaCrosby, but he said he couldn’t discuss the details because of medical confidentiality rules.

Rather than moving other seniors like LaCrosby into ground floor units, Mercy and the city are looking at ways for those residents to move somewhere else. A recent document from Olson Lee at the Mayor’s Office of Housing reads, “…We did an assessment of the households and discovered 36 frail seniors living in the development. These frail seniors are now moving to care facilities creating vacancies.”

When this news was brought to the attention of tenants, they were shocked to learn that their neighbors and friends might be moving without their knowledge.

“Are senior residents going to be displaced against their will because of their age?” asked Midtown resident Khalid Smahi. “I can’t imagine the stress and anxiety that our elders are going through—especially now with the Mayor’s Office plan to displace them to senior housing.”

At this point, there is no evidence that any seniors have been moved against their will, and some may want to live in housing with more supportive infrastructure. In fact, it would be illegal, and pretty radical, for Mercy to force anyone out of the place on the basis of age. But the lack of clear communication with tenants has created more bad feelings.

GOING FORWARD

The Mayor’s Office of Housing and Mercy Housing have recently applied for and received $90 million in federal funds. That money can go toward renovation work – but under federal rules, only if the units are occupied by people who certify that they are low income.

Mercy Housing currently has plans for the demolition of at least two buildings at Midtown and the construction of one senior housing building and one family housing building. Earlier plans on the SF Planning website showed a document for a plan that would involve the demolition of all six buildings, but the Mayor’s Office of Housing has said that this was a “clerical error” and has since removed it from their website.

In the current plan, both new Mercy apartments would be rebuilt with many units significantly smaller than existing apartments, would contain ground-floor retail, and importantly, would include 20 market-rate units in a “mixed-income” structure.

Mercy President Shoemaker told us that he’s been meeting with tenants and trying to find ways to make the situation work in the long term. He said he wasn’t sure Mercy Housing needed to be, or should be, the manager of the property in the future.

In the meantime, Mercy Housing has hired the public relations firm Barbary Coast, ostensibly to help clear up what they consider public misconceptions about Mercy’s role at Midtown.

Mercy Housing has recently attempted to create an “Advisory Committee” of tenants to participate in the ongoing talks over the future of Midtown. The problem is, only tenants in “good standing” with Mercy are allowed to participate. This excludes tenants on rent strike and tenants who are refusing the terms of the new lease—specifically, the tenants who have been the most opposed to city policy and Mercy’s management of Midtown.

Residents have formed a tenant’s group, the Midtown Tenants’ Association, which they hope can be a voice for tenants in their struggle. The democratically-elected body will include long-term former members of the Midtown Park Corporation, as well as new, previously-uninvolved tenants. The association intends to work together as an organized body to plan for a tenant-owned and managed future at Midtown.

The Council of Community Housing Organizations, which represents affordable housing groups in the city, released a statement saying that the 2007 Board of Supervisors resolution is “an appropriate framework” for achieving long-term stability for Midtown and keeping it as a part of the City’s affordable-housing stock. The statement cites the five key goals of the 2007 plan:

1) No displacement

2) Long term affordability

3) Tenant involvement

4) Decent, safe and sanitary housing

5) Explore alternative ownership structures

In the 1960’s, Redevelopment became a lightning rod for grievances that Black activists had with the City of San Francisco and its white political elite. Groups such as the Western Addition Community Organization formed to contest the course of Justin Herman’s abrupt transformation of much of San Francisco’s historical Black neighborhoods, implemented under the guise of slum clearance. Activists argued that what city planners called Redevelopment or Urban Renewal was nothing more than “Negro Removal,” to quote the famed Black author and intellectual James Baldwin who visited San Francisco during that time.

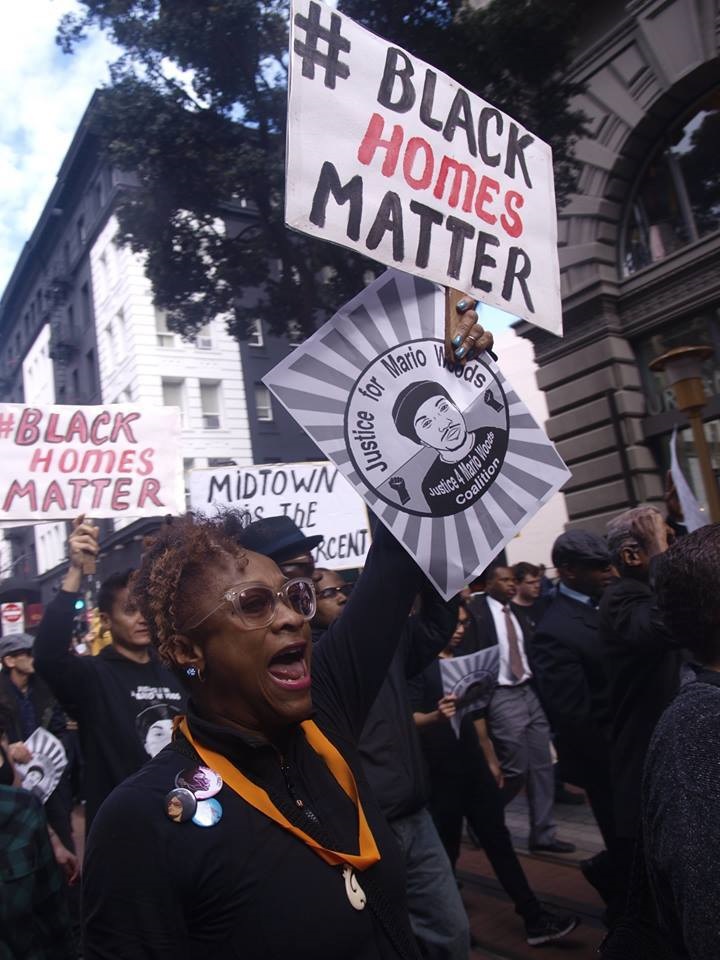

Many Midtown residents see their battle for secure housing and respect as part of a larger resurgence of Black activism in the Bay Area and the country. Participants in Midtown’s tenants’ committee have recently broadened their struggle to join in demonstrations against the deaths of Mario Woods, Alex Nieto, and Amilcar Lopez, young men of color recently shot and killed by the SFPD, around whom a broad coalition of activists have recently coalesced. Within the larger context of “Black Lives Matter”, tenants have come together under the slogan of “Black Homes Matter”. For them, racial justice is not just about the end to police brutality but also the failure to prevent mass Black displacement from San Francisco.

In a 2015 city survey of homelessness in San Francisco, 36% of respondents identified as Black—this in a city with a diminishing Black population now hovering around just 5% overall (compared to 13.4% in 1970, two years after the opening of Midtown). A recent informal survey of homeless residents living in an encampment under the 101 overpass in the city’s South of Market district, up to 60% were former San Francisco tenants evicted as recently as within the past year.

“The city’s own task force [on San Francisco’s African American “outmigration” problem] recommended several times that San Francisco ought to take steps to slow or stop the African American outmigration,” says Rachel Brahinsky, a professor of urban affairs at the University of San Francisco who has studied the history of Redevelopment and racial politics in the Fillmore. “City officials have regularly declared their intent to repair the damage of the Redevelopment era. The fight over the Midtown Park Apartments offers the city an opportunity to revive its ethical commitment to the Western Addition and to taking a clear stand against displacement.”

In the short term, the city and Mercy could easily agree to keep the tenants under stable rents. (In fact, during the rent strike, that’s in effect what’s happening, since Mercy hasn’t moved to enforce the new leases while the issue is in court).

In the long term, it’s going to be more difficult to finally fulfill the 50-year promise of equity ownership for a community displaced during Redevelopment.

Shoemaker told us that he’s not planning to take any action until the courts rule on the rent-control issue, but at some point soon, that’s going to happen. And if the court rules against the tenants, Mercy Housing is going to be in a difficult bind.

If the nonprofit is going to follow the rules and patterns of affordable housing in this city – and federal law – some tenants are going to have to pay more rent, and if they don’t, Mercy is going to have to take the politically unpopular and unpleasant step of starting evictions. That will lead to more protests and anger – and is, frankly, the last thing Mercy wants or needs.

The city and Mercy could agree to keep Midtown under rent control (and the city, which was largely an absentee landlord, could accept its responsibility for paying some of the deferred maintenance costs). That would be a large chunk of money from the General Fund (some upgrades, like elevators, are incredibly expensive).

And rent control has a big problem: Once a tenant vacates a unit, it reverts to market rate. That could, in the long term, mean that Midtown is no longer affordable. Nonprofit housing is affordable forever, with rents based on family income.

The tenants we’ve spoken to understand that, since this is public property, they are never going to get traditional equity ownership – that is, they won’t be able to buy their units and sell them for profit.

The Land Trust suggests a mixed-ownership plan, where some tenants could continue to rent units governed under rent control while others could be part of a land-trust co-op.

Of course, the management question comes up: If rent-controlled tenants leave, will rents on those units rise to market rate? Who would decide? A co-op board made up of residents who own their units might want to maximize revenue – and those units would be lost as affordable housing forever.

If the city – particularly the Mayor’s Office – had shown any kind of leadership over the past 20 years, Midtown would not be in the situation it is now. Now, with the tenants distrustful of both the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Mercy Housing —for good reason —city officials need to step up and find a way forward.

Any solution would have to protect the Midtown Park Apartments as part of San Francisco’s dwindling affordable housing stock, in perpetuity, and at the same time recognize that Midtown has a unique history and a community of tenants.

Dean Preston, a candidate for supervisor in D5, suggests that the city can easily fix the rent-control problem:

The Board can modify the relevant Rent Ordinance language to bring Midtown under rent control. Such legislation would take minutes to write, a few months to pass, and would leave residents with greater security in their homes. It would also help defuse what has been a difficult conflict between Midtown Tenants and Mercy Housing, one of the leading affordable housing providers in San Francisco.

This, he notes, has happened in the past, when he and Sup. Aaron Peskin changed the rules to protect a place on Post St.

That would assure the short-term goal of stable rent for existing residents.

But there are tenants who still want to pursue some sort of co-op ownership. The tenants we’ve spoken to understand that, since this is public property, they are never going to get traditional equity ownership – that is, they won’t be able to buy their units and sell them for profit.

And none of that is consistent with the existing nonprofit affordable housing model. The Council of Community Housing Organizations – of which Mercy is a member — is open to exploring new ownership models. Like Midtown itself, the final model might have to be unusual and unique.

Most important to any solution is that Midtown remains affordable housing forever. Midtown should be affordable for its current residents—and for their children and grandchildren.

And that’s not going to happen – without serious political upheaval – unless the existing tenants are treated as real stakeholders and play a major role in deciding Midtown’s future.