48 hills’ “Facebook money and California housing” series delves into the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s multi-million-dollar funding of the pro-growth shadow government that’s reshaping California housing policy. The first installment focused on the cabal’s push for Senator Nancy Skinner’s SB 330. The second installment tracks its efforts in behalf of Assemblymember David Chiu’s AB 1487.

The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative website states that on an unspecified date—I’m guessing February 2017— the foundation gave a group called Enterprise Community Partners $500,000 “to support Enterprise’s efforts to plan and implement a resourced and impactful regional housing enterprise that will help build capacity for a regional body to sustainably support affordable housing for the long term.”

Fast forward to 2019: Enterprise is one of two sponsors of AB 1487, the San Francisco Bay Area Housing Finance Act. The other sponsor, the Non-Profit Housing Association of Northern California, is also a CZI grantee.

Authored by San Francisco Assemblymember Chiu, AB 1487 would create the Bay Area Housing Finance Authority. The bill embodies recommendations of the Committee to House the Bay Area, or CASA, the ad hoc pro-growth lobby convened by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission.

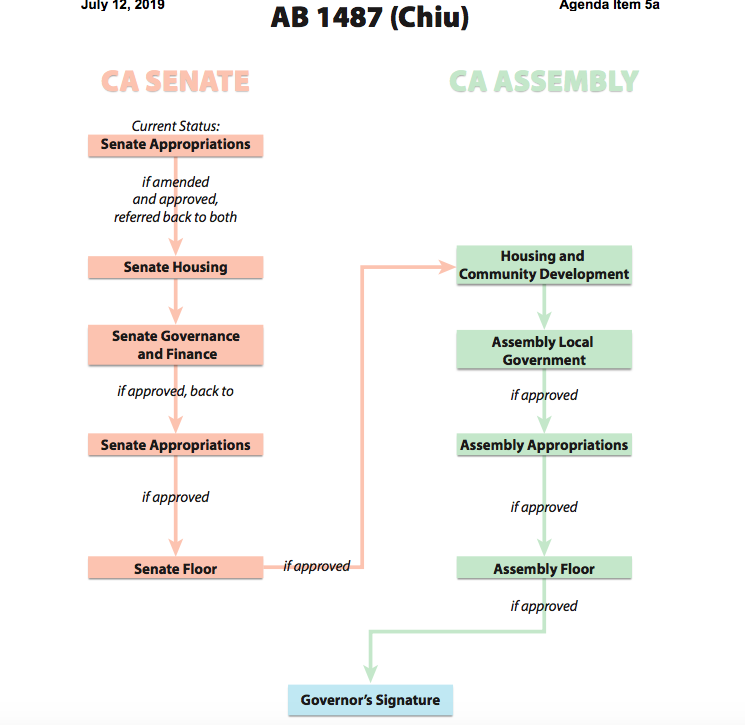

AB 1487 zipped through the Assembly and then a June 19 hearing before the Senate Housing Committee, which is chaired by Scott Wiener. Its next stop was the Senate Governance and Finance Committee, which, on July 10 considered a draft version dated July 3.

Citing an “annual funding shortfall of $2.5 billion” in the Bay Area’s “efforts to address the [region’s]affordable housing crisis,” the July 3 draft authorized the new authority to

— Raise and allocate revenue through bonds; special taxes, including a parcel tax, a gross receipts tax; an employer head tax; and a commercial linkage fee;

— Allocate funds to various cities, counties and other public agencies and affordable housing projects within its jurisdiction to finance affordable housing development;

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

— Preserve and enhance existing affordable housing;

— Fund tenant protection programs, including legal aid, and emergency rental and relocation assistance for lower income households;

— Fund homeless shelters;

— Acquire land for affordable housing construction;

— Fund infrastructure needs associated with increased housing production;

— Establish affordable housing benchmarks; and

— Determine the region’s housing needs

Senate Governance and Finance Committee Chair McGuire opened the July 10 hearing by announcing that most of the July 3 text would be gutted, and a “shell of the bill” would be moved to the Senate Appropriations Committee. Neither specified nor discussed at the meeting, the details of the evisceration had been negotiated behind closed doors. The stripped measure was posted on the Legislature’s website on July 11 (details below). On July 12, the Legislature went into its monthlong summer recess.

McGuire said that the plan is for state legislators to spend the next month negotiating a consensus with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and the Association of Bay Area Governments that results in an amended bill that the Appropriations Committee can approve in “30 to 40 days.”

On July 29, Appropriations Committee Staff Director Mark McKenzie told me that AB 1487 is now set for a hearing on August 19. “If they bring us the amendments by August 13, we could hear the amended version on 8/19. If not, we would hear the bill in its current form.”

At the July 10 hearing, Enterprise Community Partners staffer Geeta Rao, speaking in support of the measure, brandished an ECP report that she had co-authored, “The Elephant in the Region: Charting a Path for Bay Area Metro to Lead a Bold Regional Housing Agenda.” That document and Enterprise’s other efforts in behalf of a regional housing entity make explicit what every version of AB 1487 has left implicit: The pro-growth regime sees the bill as an opportunity to

— Decimate Bay Area cities’ authority over land use

— Penalize cities for failing to do what cities don’t do anyway —build housing

— Aggrandize the monied rogue Metropolitan Transportation Commission

— Facilitate the private appropriation and exploitation of the region’s public land

— Put the region’s most vulnerable tenants at greater risk of displacement

— Succor the private housing industrial complex; and

— Promote an improvident pro-growth agenda.

I think some form of AB 1487 is going to be approved by the Legislature. The question is how much of the autocratic, build-baby-build agenda the CASA lobby can persuade lawmakers to include in the measure by September 13, the last day for each house to approve legislation.

What is Enterprise Community Partners?

Operating largely out of the public limelight, Enterprise Community Partners, a 501(c)(3) non-profit headquartered in Columbia, Maryland, is a power player in the national affordable housing finance industry. From the ECP website:

We deliver the capital, develop the programs, and advocate for the policies needed to create and preserve well-designed homes that people can afford in inclusive and connected communities.

Besides ECP, the Enterprise “family” includes three subsidiaries that offer tax-exempt financing or develop housing, and two taxable “members” that provide asset management services or “multifamily and commercial real estate financing.”

The website says that since its founding in 1982, Enterprise has invested $43.6 billion in 585,000 “affordable and workforce homes.” The company “help[ed] write the legislation” that created the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit equity program, currently the major source of public funding for low-income housing in the US. Self-described as “one of the nation’s leading syndicators” of LIHTC equity for affordable housing development, Enterprise brokers tax credits between allocating agencies—in our state, the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee (CTCAC)—and private developers. Enterprise says it’s invested $13.6 billion in LIHTC equity.

With offices in San Francisco and Los Angeles, Enterprise is deeply involved in California affordable housing finance, affordable housing development, and housing policy. ECP sits on the California Fair Housing Task Force, the committee appointed by CTCAC and the California Department of Housing and Community Development to develop “opportunity maps” for the siting of LIHTC projects, an undertaking that also involves three other Chan Zuckerberg Initiative grantees, the Haas Institute and the Terner Center for Housing Innovation—both at UC Berkeley—and the California Housing Partnership Corporation.

The role of private nonprofits in building affordable housing in California – particularly in the Bay Area – is critical to any discussion. Since the Reagan Era, the federal government has completely defunded public housing, allowing existing housing stock to deteriorate and spending zero to allow cities to build new public-sector units. Neither the Clinton nor Obama Administrations did anything to change that.

While public-sector housing has been a great success in Western Europe, it’s been mostly a failure in the United States for a long list of reasons.

The community-based nonprofits that emerged out of the 1960s and 1970s have become the only affordable housing providers in cities like San Francisco. Those groups – including the Chinatown Community Development Center, TODCO, and others — have built some 30,000 units of well-managed, permanently affordable housing over the past few decades.

But the community-based nonprofits in SF are not all supporting Chiu’s bill.

In northern California, Enterprise Community Partners is involved in some admirable projects: chairing the board of the San Francisco Housing Accelerator Fund, a public-private partnership that’s raised $70 million to produce and preserve affordable housing in the city; assisting the Sustainable Chinatown Initiative, a project of the Chinatown Community Development Center, San Francisco’s Planning Department and Department of the Environment that seeks to protect the neighborhood’s distinctive identity and culture, create more affordable and resource-efficient housing, and improve access to parks and other community services; and investing, via Enterprise Community Investment, a 501(c)4, in the recently opened Pauline Weaver Senior Apartments in Fremont.

And then there’s ECP’s Chan Zuckerberg-funded campaign for a Bay Area regional housing entity. One of the peculiarities of the CZI grants list is that the dates on which the awards are made do not appear. The list states only the grant period—for CZI’s $500,000 grant to Enterprise, 2018 to 2020. The dates matter, because they illuminate connections between CZI funding and its grantees’ concerted politicking.

My query to CZI about the date of the grant to ECP ran up against the limits of Chan Zuckerberg’s purported openness: the organization has refused to provide the date. But when it comes to public disclosure, Enterprise is worse. CZI responded initially to my queries with a half-hour interview and a subsequent, albeit cursory, exchange of emails; my overtures to ECP have simply gone unanswered.

I’m guessing that CZI made the Enterprise grant in February 2017, for three reasons. First, that’s when it reportedly made a slew of other housing grants. Second, that’s when it reportedly made its $443,500 grant to the Terner Center for Housing Innovation, an another award that’s good for 2018 to 2020. Third, and most importantly, that timing jibes with the December 2017 publication of Enterprise’s report, “The Elephant in the Region.”

Sucking up to MTC

Authored by Heather Hood, Enterprise vice president and market leader for Northern California, and Geeta Rao, enterprise director, Connected Communities, Northern California Market, the 40-page ECP report identifies the region’s “elephant” as “the lack of a regional or city housing finance authority (HFA)” that could supplement the inadequate state and federal resources with “permanent regional and local sources of funding,” “activate public, surplus, and private land,” deploy “high-touch technical assistance to jurisdictions,” and “support mixed-income financing mechanisms and developments.”

Hood and Rao nominate Bay Metro as the ideal venue for the proposed authority. “Bay Metro” usually refers to the uneasy collaboration between two of the region’s planning agencies, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and the Association of Bay Area Governments. Both are housed in MTC’s fancy new digsin San Francisco’s new financial district. In “Elephant,” however, Bay Metro effectively refers to MTC, the region’s transportation planning and funding agency.

The region, we’re told, needs “[a] long-term regional housing finance structure” with “the ability to leverage lower-cost capital…and invest in housing both as a financing source and as a subsidy,” using

a combination of low-cost, tax-exempt debt, gap funding contributions, and…property tax mitigation for very low- to moderate-income units that could result in thousands of new affordable units. Bay Metro is best situated to implement this housing finance model[,] given that it already has bonding authority and is engaged in sophisticated financial markets.

ABAG doesn’t have bonding authority. They’re talking about BATA, the Bay Area Toll Authority, which currently has $9.7 billion of outstanding debt. BATA has the same board as MTC, which administers the bridge tolls.

The MTC designation is explicit in “Elephant”’s accolades for the regional transportation agency. “We have already seen the positive impact on transportation that comes from MTC coordinating planning, funding, and capacity-building at a regional scale across 27 transit operators,” write Hood and Rao. “To improve housing outcomes across the entire region, we need an entity with the authority and acumen to lead a similarly well-coordinated, impactful, and holistic housing process.”

Anyone who’s recently navigated the Bay Area’s jammed, decrepit roads or sparse public transit can only gape at this tribute to MTC’s “acumen” and “positive impact on transportation.” The absurdity of Enterprise’s homage becomes even more blatant, when you consider the agency’s loss of $120 million worth of bridge tolls on credit swaps gone bad, the $91 million of cost overruns on its new headquarters, and MTC’s deep involvement in the Bay Bridge debacle, whose $6.5 billion price tag was 2,500 percent over the original estimated cost.

But “Elephant” is, after all, among other things a solicitation for business—the business of affordable housing investment and development—by a party that has skin in the game and one, moreover, that has had a long and lucrative relationship with MTC. A PRA request asking to see documentation of funds MTC disbursed in behalf of CASA between March 6 and July 13, yielded an invoice from Enterprise Community Partners showing that since January 1, 1998, MTC has paid ECP $159,278,900.

“Given Enterprise’s particular expertise,” write Hood and Rao in “Elephant,” “we focus on actions that directly support housing preservation and production, but strongly encourage the new housing entity to include policy and capacity-building functions related to tenant protections as well.” [emphasis in original] That coy advertisement echoes in “Elephant”’s repeated plugs for the regional housing entity to hire “development experts.” The discounting of tenant protections and “capacity-building,” because those specialties fall outside “Enterprise’s particular expertise,” illustrates the report’s self-aggrandizing motives and Enterprise’s market-skewed priorities. Surely the $500,000 grant could have funded a tenant protection expert or two.

Hood and Rao aren’t just looking out for Enterprise; they’re fronting for private investment in the housing industry at large. They urge private involvement in the provision of affordable housing as a remedy for Bay Area cities’ alleged failure to do the job. Accordingly, a corollary of their marketized pitch is an indictment of local land use authority.

“Local jurisdictions alone cannot solve the housing challenges we face, and when they fail to provide solutions within their own boundaries, they export the crisis to other parts of the region….Some communities have stepped up, but most have failed to build their fair share of affordable homes.”

They attribute this failure to Prop. 13, the 2012 dissolution of redevelopment agencies and attendant loss of local funding for affordable housing development, localities’ “circuitous” and “unpredictable permitting” processes, and “[t]he ever-present challenge of all kinds of NIMBYism.”

The Nimby rap

Only the Nimbyism factor is accompanied by specific examples: “a lawsuit brought against the City of Lafayette for denying what would have been a 315-unit moderate-income development in favor of a significantly lower density proposal aimed at higher-income households, and the City of Brisbane’s rejection of any housing units as part of its proposal to accept eight million square feet of new commercial and industrial development.” That’s the full extent of “Elephant”’s documentation of Bay Area Nimbyism, a term that the report doesn’t bother to define. Both examples are problematic.

The lawsuit against Lafayette, concerning a development on Deer Hill Road, was brought in 2016 by Yimby pioneer Sonja Trauss and the Bay Area Renters Federation, which subsequently morphed into the California Renters Legal Advocacy and Education Fund. The documents associated with the suit appear on CaRLA’s website in a list that concludes with the declaration: “We won!”

Really? The final ruling of the court, posted on the website, denied the Trauss/BARF petition, stating that “the Developer has maintained that the decision” to suspend the larger development and move forward with the smaller one was “voluntary.”

Presumably Hood and Rao view the lawsuit, regardless of its outcome, as evidence that local residents are routinely blocking new affordable housing in the Bay Area. If so, a few questions are in order. Should affordable housing be built anywhere it can get approved? In this case, the project was planned for a site with hourly bus service, right off Pleasant Hill Road, which is already packed at commute time. Wouldn’t this encourage sprawl and worsen congestion?

As for affordability: “moderate income” usually means household income at or above 80 percent the Area Median Income. For Contra Costa County in 2019, the HUD-designated income at 80 percent AMI for a four-person household is $134,050. Nothing moderate about that.

The Brisbane example is also dubious. “Elephant”’s claim that “the City of Brisbane” rejected “any housing units as part of its proposal to accept eight million square feet of new commercial and industrial development” references an editorial that appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle on September 25, 2016, under the headline “Brisbane shouldn’t hide from Bay Area reality.” Unnamed in the ECP report, the development was the Baylands project. What the Chronicle editors meant by “reality” was “a booming economy and surge in population” that have not been matched by a commensurate amount of new housing. The editors opined:

City leaders in the tiny town are ruling out condos and apartments in a mega-development smack in the center of the Bay Area’s costly real estate marketplace. The hamlet, population 4,282, favors up to 8.3 million square feet of shops and offices alongside the 101 freeway. What it doesn’t want is Part Two of the [developer’s] plan: some 4,434 residential units.

Sneering at “benign arguments about losing its small-town feel to a project that could [sic] double its population,” the Chronicle urged Brisbane show that “one Bay Area community isn’t afraid to accept its role in a wider region.”

In fact, as of September 25, 2016, Brisbane hadn’t rejected or approved anything. The residence-free alternative was one of four scenarios presented in the Baylands’ Environmental Impact Report. That scenario had been dubbed the “Community Proposed Plan” by the town’s planning director. Former Brisbane Mayor Ray Miller told me that residents protested that name, because their say in the plan’s formulation had been very limited, and in particular had excluded consideration of housing. And the Baylands property is not, as the Chronicle stated, merely “empty dirt where a dump and rail yard were the last notable activities.” It’s a Superfund site.

As with Lafayette, so, too, with Brisbane: It’s the principle of the thing that matters. What principle, then, justifies the argument that one town has to accommodate the out-of-control, unplanned commercial growth approved by other towns? It could only be the belief that Growth is God and thus needs to be appeased. That’s not reality; it’s a lethal delusion perpetrated by the capitalist growth machine. Like the Chronicle, Enterprise touts that fantasy. The report approvingly cites Plan Bay Area’s “bold vision for the San Francisco Bay Area to grow equitably and sustainably as our population increases from seven million to nine million by 2040.”

Cities don’t build; developers do

Contrary to “Elephant,” communities, i.e., cities, do not typically build homes, at least not any more (since the demise of most federal housing money). Private developers do—when they do. Cities approve housing—or don’t. A big reason they don’t in California is that Prop. 13 constrains property taxes, thus moving local officials to prefer commercial development—retail and offices—which needs less services than new housing.

Hood and Rao mark “the severe blow” that Prop. 13 “continues to deal…to most cities.” But they eschew the logical next step entailed by recognition of that blow: pushing for amendments to the law that would yield more revenue. It’s not that they’re adverse to changing tax laws. On the contrary. But they want to lowertaxes, not raise them, to subsidize the affordable housing industry.

For example, they think “underutilized, abandoned, and tax-defaulted land” should be placed in a regional land bank and made available for housing development. “[D]uring holding periods,” the “land coordinating entity” should have the authority to waive state and local taxes on its deposits. Hood and Rao also think the entity should “serve incomes beyond the typical range of 60% of AMI [Area Median Income, as defined by HUD] and below,” by subsidizing mixed income developments in which the higher market-rate rents “will support the lower-income units while also serving people in the middle who are currently without any assistance.” Critical to the success of such development, they say, is extending property tax reductions if not outright exemptions to housing for households earning between 81% and 120% AMI.”

California’s Revenue and Taxation Code currently “exempts non-profit-owned, deed-restricted housing serving households earning up to 80% AMI,” a provision that, the Enterprise staffers write, “in conjunction with subsidies and below-market loans, makes developing and operating affordable housing possible, since affordable rents [at this level] cannot cover both normal operating expenses and property taxes.” This same section of the code “also explains why so few developers build housing to serve households earning between 81 percent and 120 percent AMI, despite a tremendous need at this affordability level.” Hood and Rao suggest that before the Legislature amends the statewide tax code to expand the exemption beyond “’units serving lower income households’ to ‘units serving low- or moderate-income households,’” “it may make sense to explore a pilot for the Bay Area.”

Again, “Elephant” doesn’t tie Area Median Income, “lower- and “moderate-income” housing to dollar amounts, leaving these terms conveniently abstract. Here are the numbers: The current AMI for the HUD Area that includes San Francisco and Marin is $123,150; 80%, AMI is $98,500; 120% AMI is $148,800. In other words, Enterprise wants to subsidize housing—or more precisely, the builders of housing—for the wealthy. As noted, the report’s brief for such subsidies, when they’re folded into mixed-income developments, rests on the argument that without the supplemental market-rate rents, building housing for the neediest is not financially viable—that is, doesn’t yield the ROI required by private developers—particularly in the Bay Area.

Building for the neediest would be a lot more viable if we closed the giant loophole in Prop. 13 stipulating that property is only reassessed when it changes hands. That provision has shifted the state’s property tax burden onto owners of single-family homes, which are sold much more frequently than commercial parcels. No such proposal appears in “Elephant.” That’s because Enterprise wants to use public assets to lower the risk of private investment in housing.

To achieve that goal, “Elephant” also proposes to have the regional housing finance authority:

— sell low-interest (1-3 percent) tax-exempt bonds to fund “low cost-construction and permanent loans to housing developers”

— supplement 4 percent Low Income Housing Tax Credits with low-interest loans and “deferred, ‘soft’ loans and grants” to housing developers;

— “take an equity position (deeply subordinated) in housing projects

— write letters of credi

— impose parcel taxes for affordable housing à la Seattle’s Housing Affordability and Livability (HALA)

— make “surplus” or “underutilized” public lands available to the private housing industry via a land bank run by the regional housing entity.

Regional land banking as authoritarian capitalism

Summarily addressed in the EPC report, the land banking concept is fleshed out in a report referenced in “Elephant”’s footnotes as a “forthcoming study on Public Lands by Bay Metro, to be released” (39). The study was published on September 11, 2018, under the nondescript title “Technical Memorandum.” Its declared subject—“MTC Workforce Housing Action Plan”—is only slightly more informative. A precise title would be “State-led and -enforced Privatization of Public Lands Action Plan.” The consultant authors had worked for two years with other consultants and a sixteen-person public-private Technical Advisory Team that included Hood and Rao.

As with “Elephant,” comprehending this “Action Plan” is an exercise in textual deconstruction. The title specifies “workforce” housing. The first sentence says that MTC hired the consultant team “to evaluate opportunities to develop publicly owned properties in the nine Bay Area Counties as affordable and workforce housing.” A few lines down, we read that the Action Plan addresses “the regional and state-wide need for housing generally and affordable housing in particular.” What are they really talking about? Is there a difference between workforce and affordable housing?

You bet there is. Footnote 2 hints at it:

For this study, “affordable housing” means units for households earning up to 60 percent of median income, as those typically are eligible for common subsidy programs such as Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) and Section 8 vouchers. “Workforce housing” means units for households with income below that required to secure quality market-rate housing, typically those in the 60 percent to 120 percent of AMI range, though in some communities with very high housing prices[,] “workforce housing” may include households up to 150 percent of AMI or greater. Use of one term or the other in this document does not necessarily preclude the application of actions to the other housing category.

The final sentence suggests that MTC is playing a shell game.

To understand better what’s under each shell, consider the relevant Area Median Income dollar amounts. For a four-bedroom household in the San Francisco-Marin County HUD Fair Market Rent Area, the current AMI is 60 percent $73,400; 120 percent, $147,800; at 150 percent, $184,750. You get the picture: the report sugarcoats MTC’s solicitude for the wealthy as “housing that is affordable to the majority of households” in the Bay Area.

Next euphemism: “publicly owned properties.” (1) By page 2, it’s clear that what the authors really mean is public land near transit, as indicated by “Table 1: Public Land Suitable for Housing Near Transit” and the accompanying statement: “This Action Plan provides a set of recommendations to develop publicly owned properties near transit services in the Bay Area for affordable and workforce housing.” The chart lists “nearly 700 acres of developable parcels, estimated to have capacity for roughly 35,000 housing units,” as identified by “MTC and its consultants and advisors.”

The rationale for developing these properties as housing is threefold:

First: “The use of such transit-served land for housing is particularly promising, as the residents of such housing can make use of the region’s major transportation infrastructure investments.”

Second: “[T]he developers of such housing can capitalize on some funding opportunities that are specifically geared toward transit-served parcels.”

Third—and most telling:

[T]he use of public land presents key opportunities that are not typically available on private land, such as the ability to defer land acquisition costs until the project is entitled, the possibility of receiving a discounted land price to reflect the public benefit of the project, and the chance to leverage the public land contribution or discount as a ‘local match’ for competitive funding programs.

The validity of the second rationale depends on the viability of the first. Unfortunately, the first founders on reality. Yes, people who live near BART, bus and streetcar stops, “can make use of the region’s major transportation infrastructure investments,” but the unfortunate truth is that less and less of them are doing so. The problem isn’t limited to the Bay Area: despite massive public investments, transit use in California is generally declining. Though nobody in the Bay Area knows whether transit-oriented development (TOD) is working, dozens of TOD projects are underway in the region.

But of the three rationales, it’s the third—public land offers the private affordable housing industry unique opportunities for financial gain—that’s the most extensively articulated and the most concerning. To justify the exploitation of those opportunities, the “Memorandum” employs the same bait and switch rhetorical device that Hood and Rao used to acknowledge and then dismiss Prop. 13 as a major source of cities’ reluctance to approve housing: Nod toward an essential problem, and then advance a course of action that ignores, when it doesn’t worsen, the problem.

First, the nod—in this case, to the Bay Area’s population explosion, its built-out character, and public agencies’ “financial responsibilities”:

In the face of a growing regional population and a constrained supply of developable land, public agencies must be cautious about disposing of land they may need over the long term, if not the present or immediate future. Public agencies also have financial responsibilities to their constituents and taxpayers, and offering their land for less than market value and/or for developments that may not generate significant property faces can be difficult to justify from a fiscal standpoint.

Then the brush-off: “Nevertheless, many jurisdictions and agencies in the region have identified affordable housing as a key objective, and public land remains a unique asset to advance that objective.”

And finally, the aggravating plan of action: Take steps to ensure that cities surrender their land, an irreplaceable asset, to the private housing industry. To this end, the “Memorandum” makes six recommendations:

-

Declare that housing trumps all. “Cities, school districts, transit agencies, and other public organizations” should “make clear to their entire staff and constituency that they are adopting a pro-housing position and that inevitable conflicts should be resolved as favorably for housing as possible.”

-

Offer public land for less than its market-rate price. Public agencies should go beyond the Surplus Land Act’s requirement “that any California jurisdiction seeking to develop surplus land must first offer the property to developers of affordable housing” and “creat[e] policy-level flexibility to offer land for either fee simple sale or long-term ground lease, and…offer such land at prices below market-rate appraisal value to the extent that such discounts are required for affordable housing and can be recognized as a local match for other available subsidy programs.”

-

Impose new taxes to subsidize private housing developers. To fund affordable housing “production and retention,” cities and counties should levy property and/or sales tax and use “tools such as Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts,” which partly replace “previous Redevelopment resources.”

-

Deregulate local housing development. Cities and counties should reduce costs and risks of housing development by “establishing ministerial permitting or ‘by-right’ zoning for projects meeting objective standards defined by the local jurisdiction, providing program-level environmental clearance”—thereby avoiding the need for an Environmental Impact Report—“waiving or deferring certain impact fees, making public investments in requiring infrastructure or replacement parking,” “allowing affordable housing developers to acquire land at below-market prices” and “to defer the acquisition costs until a project has advanced on approvals and external funding efforts.”

-

Raise densities and lower parking requirements. Cities and counties should “enhance project feasibility” by “increas[ing] the allowed densities on both public and private land,” “encourag[ing] form-based zoning, and “allowing affordable housing projects to provide fewer parking spaces per unit.”

-

Condition transportation funding on housing production. This is the hammer and deserves to be fully cited: “MTC should use its leverage to strongly encourage jurisdictions to aggressively pursue housing development on surplus public lands. As a regional organization controlling significant funding for transportation and the responsibility to implement a sustainable development pattern for the Bay Area, MTC should direct discretionary funding to jurisdictions that have proven capable of producing housing, invest proactively in projects that face major infrastructure hurdles, fund technical studies and staff support for agencies seeking to develop their land, create flexible funding mechanisms to offer low-cost financing, and lobby for State laws that encourage the use of public lands for housing.”

MTC is already using its “leverage,” i.e., its control of millions of dollars of public monies, to pressure cities to approve new housing or forego funding. See its Housing Incentive Pool scheme, adopted in November 2018.

The “Technical Memorandum”’s concluding list of “Potential Actions for MTC” ends with an even more aggressive proposal: Adopt legislation that either adds affordable housing on public land to instances in which local land use “sovereignty” may be overridden by a state department, multi-jurisdictional regional entity or special district; or that retains land use authority in the current jurisdictions but limits their ability to reject proposals for housing development on public lands.

The Enterprise Community Partners’ report is more restrained about designs on local sovereignty. “Elephant” only cites the need for “greater enforcement mechanisms” and incentives—money, technical support—that a regional housing entity could use to remedy the current situation, in which “localities can get away with not building their fair share” of affordable housing “without consequences.”

Dispensing with such niceties, the “Memorandum” makes clear that the growth lobby wants to divest local jurisdictions of far more than their “underutilized” public lands. It also wants to usurp the land use authority of public agencies—not just cities but also special districts overseeing transit, water, and other services and infrastructure.

In another respect, however, “Elephant” shows less solicitude for public authority per se: Hood and Rao suggest that the regional housing finance entity could be overseen by a new department within Bay Metro or a “quasi-public” agency “similar to the Bay Area Toll Authority (BATA) and Resilient by Design (RBD),” also housed within Bay Metro. “

In the second approach, the quasi-public regional agency acts with the transparency and accountability of a public agency, but is empowered to play a strong role in administering additional housing resources, providing educational tools to local cities and other housing stakeholders, and intervening, when necessary, to advance affordable housing projects that may be facing financing, zoning, building code, or community hurdles.

“Elephant” says nothing about how to ensure that a quasi-public entity’s actions would be transparent and accountable. And the reference to BATA as quasi-public is disconcerting: the agency’s board is identical to MTC, a public agency, albeit one that favors stealth policymaking.

The elephant in the “Elephant”

Enterprise’s analysis of the Bay Area’s housing debacle has a major flaw: it omits the tech boom’s inflationary effect on residential real estate. The price of housing has been bid up, up, up by the tens of thousands of highly compensated tech employees who’ve streamed into the region. But what UC Geography Professor Emeritus Richard Walker has termed “insane demand” has no place in “Elephant,” where tech makes its sole appearance as a prospective partner of a regional housing finance authority. The report lauds the industry, calling on the “dynamic” sector to “bring its propensity for innovation and risk-taking to guide capital in ways that bring not only economic but social returns as well”—specifically, to help the new regional housing entity “in delivering affordable housing outcomes.” Given that the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative funded the report, the tech whitewash is perhaps only to be expected. It’s also another reason to discount “Elephant”’s analysis of and remedies for the Bay Area’s housing woes.

Next step: CASA

A 40-page report seems like a poor return on a $500,000 investment. Not to worry: the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s grant to Enterprise Community Partners yielded much more than “The Elephant in the Region;” it also facilitated the push for a Bay Area regional housing finance authority at the staging ground for many of the key housing bills introduced in the Legislature this year: CASA, the Committee to House the Bay Area.

Secretly convened and managed by then-MTC Executive Director Steve Heminger (and not also, as the CASA website states, by ABAG), the Committee to House the Bay Area formally existed from July 2017 to December 2018. It had an ambitious goal: to formulate and lobby for pro-growth housing policies that would be embodied in state legislation, some targeting the Bay Area but most applying to all California.

CASA’s proceedings exemplify the furtive character of the shadow land-use government. The group had two formal subdivisions, a Steering Committee, which was steered by Heminger; and a Technical Committee, which, with the ample aid of consultants and MTC resources, did the policymaking work. The rosters of these groups are posted on the CASA website. Not so the names of the participants of the Technical Committee’s three working groups, other than each entity’s two coordinators.

The meetings of the two main committees were noticed online, but numerous other events occurred behind closed doors and in secret, including the working group sessions and a 42-person trip to New York City. Even the two big committees’ public meetings, save the first, lack minutes. The only way to learn what transpired is to watch the videos posted on the CASA website—unless you’re looking for documentation of the Steering Committee’s April 25, 2018 meeting, which focused on taxes and housing finance. Documentation of that event has been expunged from the CASA meetings schedule and MTC Legistar records. (I have a hard copy of the agenda and notes I took on the disappeared video of the meeting.)

48hills had to sue MTC to get the agency to release documentation of the money it had disbursed for CASA. According to documents finally obtained by 48 hills, as of March 6, 2019, the figure appears to be at least $3 million. It’s hard to say exactly, because in some cases, CASA expenditures are lumped together with other costs.

CASA also exemplifies the makeup of the shadow government. Dominated by representatives of the real estate industry, it’s 50-odd-member roster also included representatives of tech, equity advocacy groups, organized labor, environmental advocates, and philanthropy, as well as a handful of the Bay Area’s 101 cities and nine counties. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative had a seat; so did Facebook and ten CZI grantees. (For more details, see the first installment of the “Facebook money and California housing” series.)

Enterprise did not have a regular seat at CASA but was deeply involved in the group’s proceedings. Documents obtained by 48 hills include a February, 28, 2018, letter from Heminger to CZI Chief of Staff and CASA Technical Committee member Caitlyn Fox and San Francisco Foundation CEO and CASA co-chair Fred Blackwell regarding “Cross-Sector Partnership on Select MTC/ABAG Housing Initiatives.”

“This letter,” wrote Heminger, “follows up on our telephone conversation before the holidays.” He identified three of his agency’s housing initiatives that “lend themselves to cross-sector partnerships with non-governmental funders/partners:”

— Regional Infrastructure Bank: would provide a low-cost financing tool to local jurisdictions to accelerate construction and delivery of infrastructure projects and that could serve as a model for “a similar tool that could potentially be used to support housing projects.

— Housing Incentive Pool, a $76 million challenge grant program that “will reward jurisdictions that build and preserve the most [very low, low, and moderate-income level] housing units between 2015 and 2020, based on the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) for the 2014-22 cycle.

— Regional Housing Trust Fund: would pool resources from multiple sources to fund affordable housing projects in Priority Development Areas and Transit Priority Areas, helping to fill the funding gap left by the dissolution of redevelopment agencies

Heminger invited Fox and Blackwell to contact Bay Metro Planning Director Ken Kirkey for more information, suggesting that “we could meet after the next Technical Committee meeting on March 28.”

Another document obtained by 48 hills is a letter dated March 22, 2017—is the 2017 date a typo that ought to be 2018?—on ECP letterhead from Hood and Rao to “Ken Kirkey and Team, Metropolitan Transportation Commission” re “Scope for Bay Metro to Support CASA with Research.” The letter begins by thanking its recipients

for entrusting us to be a thought partner as your team advances a variety of housing solutions….We would glad to support you in this important work. We estimate the total cost for the following work to be $50,000 and can contribute $25,000 of that time and materials in kind (paid by grants we have already secured).

Presumably “grants we have already received” refers to the CZI award.

Hood and Rao list six “Topics Enterprise’s Northern California office can assist MTC on research and analysis, and potentially explore policy options for CASA:” “Regional housing trust fund,” “Redevelopment 2.0, “Infrastructure Bank,” “Tax on Vacant Units/Parcels,” “Numeric Targets for CASA,” and “Research Priorities for Incentives and Tools”— the last specifically addressing “Public and surplus lands.” They offer to produce “3-10 page summaries for each topic, along with many meetings.”

48 hills also obtained a contract in which MTC agreed to pay Enterprise Community Partners $25,000 “for the performance of professional services in connection with research and analysis support on CASA” to be provided between May 30 and July 31, 2018. Along with project management and coordination, the scope of work involved developing a fact sheet and action plan for four topics, to be reviewed by the CASA Technical Committee:

— Redevelopment 2.

— Regional or sub-regional housing trust fun

— Regional tax on vacant parcel

— Publicly-owned surplus lands

EPC staff did the assigned work, apparently in concert with the other future co-sponsor of AB 1487, the Non-profit Housing Association of Northern California. The agenda of the Technical Committee’s May 16 meeting included a proposal from the Affordable Production Sub-Work Group to “Support the Creation of a Robustly Resourced Regional Housing Fund” and to “Capitalize on the oversupply of vacant and/or underutilized commercially-zoned properties across the Bay Area” via new state legislation creating “an emergency, 15-year zoning overlay which makes housing an allowable use on sites zoned for commercial, retail, and institutional uses.” The accompanying attachments were produced by NPH.

The agenda for the Technical Committee’s July 18 meeting included proposals to “Recreate Redevelopment Agencies with a Focus on Affordable Housing” and to “Promote the Creation of Affordable Housing Authorities in Each County and at the Regional Level,” both presented by NPH staff; and proposals entitled “Modify State Housing Element Law to Require Public Land Identification and Incentivize its Development with Affordable Housing” and “Regional Actions to Support, Incentivize, Enforce Housing on Public Land,” both presented by Hood and BART Transit-Oriented Development Program Manager and CASA member Abby Thorne-Lyman.

ECP staff made one more public appearance at CASA. At the end of the Technical Committee’s long meeting on September 19, 2018. Hood spoke for five minutes about the need for a regional housing trust fund, focusing on possible funding sources and the legal status of a Bay Area fund.

The agenda for that meeting included a two-page recommendation to “Create an [sic] Regional Housing Trust Fund that collects revenue, creates programs, and disburses funding at a regional level” and to “[p]air it with the incentive and capacity building work of a proposed regional housing entity.” The document mentions “a recent forum hosted by Enterprise Community Partners and Nonprofit Housing Association of Northern California, a forum of practitioners that included MTC and ABAG staff, as well as Michael Anderson from the Center for Community Change (an organization that hosts the national initiative to help track the challenges and successes of HTFs).” To my knowledge, that forum was never publicly noticed, nor was a record of its proceedings posted by either of the two public agencies in attendance.

The agenda of the Technical Committee’s September 19 meeting included the first draft of what would become the bundle of proposed state legislation known as the CASA Compact. The Compact’s initial iteration comprised seventeen “elements,” each a proposal for state housing legislation. Element 6, “Significant Regional Revenue Streams,” and Element 17, “Creation of a New Regional Housing Entity,” contained rudiments of AB 1487.

The secret CASA junket to NYC

Hood’s presentations to CASA were warmups for Enterprise’s star turn, a performance that took place thousands of miles from the Bay Area. Documents obtained by 48 hills show that in early December 2018, ECP teamed up with MTC and the San Francisco Foundation to co-host a three-day trip to New York City for a 42-person delegation that included Hood, Rao, Fox, Non-Profit Housing Association of Northern California Executive Director Amie Fishman, Facebook Policy Programs Manager Maya Perkins, Assemblymember Chiu, and his then-Chief of Staff Judson True (shortly after returning from New York, True was appointed Director of Housing Delivery by San Francisco Mayor London Breed). True had addressed the CASA Steering Committee at its April 25, 2018 ,“Tax and Fiscal Policy Workshop.” Chiu’s and True’s travel expenses were paid by MTC.

An entry in the Enterprise blog described the trip as “a learning session on New York’s housing funding and finance system.” The agenda for the trip, never posted by CASA or MTC, was obtained by 48 hills (a partial version appears in the Enterprise blog piece). It shows that the visitors were greeted at ECP’s New York office by Hood, Rao, and Enterprise’s then-CEO, Terri Ludwig. The CASA delegates also hobnobbed with public and private notables in the city’s housing finance industry. Back in the Bay Area, none of them publicly shared what they’d learned.

“Elephant” hints at the curriculum. The ECP report cites New York City as “a great example of how to create a range of housing from preservation to new construction, from extremely low- to moderate-income, and from small-to large-scale” that could be emulated by “high-cost, coastal regions that face similar affordable housing needs, funding challenges, and a comparable political climate.” It showcases the New York City Housing Development Corporation (NYCHDC), “a supplementary and alternative means of supplying financing for affordable housing independent from the City’s capital budget” that

issues bonds and provides subsidy and low-cost loans to develop and preserve a variety of housing types and scales, including home-ownership. Its authorizing statute includes flexibility for NYCHDC to amend its programs and goals in response to changing economic climates.

The 50-year-old agency has availed itself of that flexibility and created “several subsidiaries and new bond programs,” to the extent that it’s “become the leading local finance agency in the nation, outperforming many of the country’s largest banks in terms of volume and dollar amount of bonds issued.” As of 2014, NYCHDC’s Multi-Family Housing Revenue Bond Resolution, established in 1993, had “over $4 billion of bonds and more than $62 billion in multi-family loans, reserves and other assets.” Since 2003, The agency “has provided over $1.4 billion in 1% subordinate loans funded from its corporate reserves since 2003.” (Subordinate loans rank below other loans with regard to claims on assets or earnings. If a borrower defaults, creditors who own subordinated debt won’t be paid out until after senior debt holders are paid in full.)

In New York, the CASA delegation attended a panel moderated by ECP staffer Judi Kende that included NYCHDC CEO, Executive Vice President, and General Counsel Richard Froehlich and NYCHDC Executive Vice President for Development Anthony Richardson.

As “the most recent example” of the “ambitious affordable housing programs” that have been enabled by “[t]he existence of an independent finance entity like NYCHDC,” “Elephant” offers New York Mayor Bill de Blasio’s “ten-year, 200,000-unit housing plan,” Housing New York, that was unveiled in May 2014. As of December 2017, NYCHDC had issued “roughly” $4.5 billion in bonds to support Housing New York. The ECP report links to the city document describing the plan, “Housing New York: Three Years of Progress,” a predictably roseate account.

NYCHDC was cited as a model for a “Bay Area Regional Housing Enterprise” on an item that appeared on the September 19, 2018, agenda of the Technical Committee. The entity “would be structured to implement the CASA Compact advancing Protection, Production and Preservation” of affordable housing—the so-called 3Ps. The same citation also appears in the second draft of the CASA Compact, posted on the November 13, 2018, agenda of the Technical Committee, and the final version of the Compact, published in mid-December 2018.

Housing New York debunked

To state the obvious, space does not permit an in-depth look at New York City housing. But given ECP’s and CASA’s commendation of Housing New York as a model for the Bay Area, it would be remiss to ignore the incisive assessment of the program made by planning scholar and community activist, Hunter College and CUNY Graduate Center Professor Emeritus Tom Angotti.

Writing in June 2014, Angotti characterized HNY as two plans, one for new housing development and the other for “keeping rents down and preserving neighborhoods.” The problem,” he said, is that the two plans contradict one another, and it looks like the development plan will be the priority.”

On the one hand, Housing New York is “a giant development scheme” that would promote “the creation of 200,000 new affordable housing units…over the next 10 years, 40 percent of them in new construction,” plus “promises of new opportunities for luxury development.”

The city would rezone in strategic areas to promote new building, allow for taller buildings, let landowners transfer their development rights to hot locations, continue tax and infrastructure subsidies to developers and streamline land use, environmental and building regulations. It’s no wonder that Crain’sreported that the city’s largest real estate developers are gushing with praise for the plan. Construction unions are also satisfied.

Like Enterprise Community Partners, Housing New York takes an elastic approach to affordability:

The new plan would shuffle definitions of affordability, making a larger proportion of units available for people in low-income brackets without changing the way “low-income” is defined (50-80 percent of the Area Median Income, which can be up to $67,000 a year for a family of four).

The preservation plan, by contrast, “speaks to the widespread frustration and anger of renters and homeowners who were and are victims of the speculative real estate fever that forces them to move out of neighborhoods they have lived in for decades and generations,” promising “that new housing, better services and community involvement will allow more residents to stay” and “tak[ing] a step away from using homeless shelters and toward creating decent housing opportunities for people in greatest need.” But as always, the devil is in the details, and “when you get down to the details,” Housing New York offers “only small steps forward and vague promises.” Ultimately, “creating new housing remains the overriding mission, not saving neighborhoods.”

As we shall see, fostering new development rather than saving neighborhoods is also the overriding mission of AB 1487 and other bills emanating from the CASA lobby. It follows that as an aid to understanding that lobby’s agenda, Angotti’s critique is most valuable when it debunks the supply-side position at large. The “trickle-down approach,” he writes,

conceals a fundamental truth: the market driving everything is the land market, not some mythical housing market. Developers and investors choose areas where future land values are higher than current ones and try to build on this land so they can make a profit from rising land values….[That is] why “dislocation” or “displacement” is a virtually inevitable companion to new development. It is the reason our neighborhoods need better means for controlling land use, not just more housing.

Angotti homes in on “de Blasio’s outspoken commitment to public-private partnerships as the basic underpinning of city housing policy.” Aiming to “’leverage markets,’” the mayor “expects that the vast majority of the funds, $30 billion, will come from the private sector, which is of course in the game to build more, make money, and produce affordable housing whenever it helps their bottom line and buys community support.” Shades of Enterprise Community Partners’ playbook.

Angotti concludes by urging “progressive individuals, groups, and coalitions” fighting for affordable housing to resist the impulse “to accept power of developers as inevitable,” an acquiescence that

leaves us to negotiate for what we can get from the development plan—more “affordable” housing or other community benefits. This defeatist notion forces us to accept the bedrock neoliberal philosophy that private power is not only a given but the only legitimate power. Government, therefore, must follow the lead of private capital.

The CASA “learning session” panel entitled “Protecting People in Place” included a presentation by ANHD Research and Policy Associate Lucy Block. I’d love to know what she said and how she was received.

From the CASA Compact to AB 1487

The only members of CASA’s New York City delegation directly associated with the state Legislature were Assemblymember Chiu and his chief of staff. On February 22, Chiu introduced AB 1487, the Bay Area Regional Housing Finance Act. Since its introduction, the bill has been amended six times. The most substantial version, containing amendments made on July 3, reflected key recommendations put forward by the ECP report and the Compact.

Stating that “a regional entity is necessary to help address the housing crisis in the San Francisco Bay Area by delivering resources and technical assistance at a regional scale,” the July 3 draft authorized the establishment of “a regional financing mechanism for affordable housing development and preservation” that could, among other things

–“Raise revenue and allocate funds throughout the San Francisco Bay Area

— “Assemble parcels and lease or acquire land for affordable housing development

— “[M]onitor progress on meeting regional and state housing goals,” an

— “Provide support and technical assistance to local governments in relation to producing and preserving affordable housing.”

Dubbed the Housing Alliance for the Bay Area, the new regional entity would be authorized to raise revenue through a parcel tax, gross receipts tax, sales tax, employee head tax, commercial linkage fee, and bonds. It would also have the authority to “[a]ssemble parcels and lease or acquire land for affordable housing development” and to “collect data on housing production and monitor progress on meeting regional and state housing goals.”

The July 3 draft bill favored production over both tenant protection and the preservation of existing affordable housing, as indicated by the following requirements for allocating revenue:

— A minimum of 60 percent of production of housing units affordable to lower income households

— A minimum of 5 percent and a maximum of 10 percent for tenant protection services

— A minimum of 15 percent and a maximum of 20 percent for preservation of housing affordable to low- or moderate-income households

— A minimum of 5 percent and a maximum of 10 percent for general funds awarded to a local government that achieves affordable housing benchmarks established by the entity, good for staffing costs to help accelerate the production of housing in a jurisdiction; infrastructure needs associated with increased housing production, including, but not limited to transportation, schools and parks; and homeless shelters.

The new entity could change these allocation percentages “if it adopts a finding that the region’s needs differ from those requirements.”

Meanwhile, another policy championed by the ECP report, embedded in the CASA Compact, and ancillary to the proposed regional housing entity—eased privatization of public land for “affordable” housing—was incorporated into San Francisco Assemblymember Phil Ting’s AB 1486. Like AB 1487, AB 1486 is moving forward in this session of the Legislature. Both bills have been endorsed by Enterprise Community Partners and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

The July 10 evisceration

As noted above, on July 10, the Senate Government and Finance Committee gutted most of the text in the July 3 version of the bill and sent a skeletal measure to the Senate Appropriations Committee. Consistent with the housing cabal’s secretive style, a backroom deal had been negotiated by Chiu, his office, and an ad hoc ABAG-MTC AB 1487 Committee. Gone were

— definitions of lower income and low or moderate income household

— a procedure for reviewing the implementation of an initial ballot measure that would fund the new regional entity

— specifications of the authority’s powers

— the entire section on revenues measures that the authority could enact

— rules governing the authority’s expenditures

Absent this drastic surgical procedure, which shrank the bill from sixteen to two and a half pages, AB 1487 likely would have died on July 10, done in by pushback from Bay Area cities and counties. By stripping out the bill’s most controversial sections, the dealmakers hoped to quell local opposition and move a bare-bones measure to the Senate Appropriations Committee before the Legislature went into its monthlong summer recess on July 12. “All the things that gave folks heartburn about the original AB 1487,” Heather Hood told the ABAG Ex. Board on July 18, “have been taken away.”

At the same time, according to an MTC ABAG staff report dated July 12, Chiu agreed to add amendments sought by the Joint MTC Legislation Committee and ABAG Legislation Committee

— Exclude sales tax from revenue option

— Ensure no new responsibilities are assigned to MTC or ABAG without a guaranteed source of ongoing funding and bill includes a provision allowing dissolution of HABA (now renamed Bay Area Housing Finance Authority), if not enough revenue is generated to be meaningful

— Authorize ABAG and MTC “to determine whether to place [revenue measures] on ballot and set tax rates, thereby determining what level of revenue is ‘meaningful’”

— Budget at least $25 million to ABAG for ‘flexible housing planning work”

— Ensure the bill doesn’t require MTC staff to report to a newly structured board but instead split up new entity’s duties between MTC and ABA

— Develop a distribution formula that distributes more than 25 percent of any employer-based revenue to a regional pool

— “[P]rovide that ‘at least 50 percent’ of head tax shall be distributed to counties, with up to 50 percent for regional pool.”

The July 12 MTC-ABAG staff report included an attachment dated June 28, 2019, detailing recommendations from the ABAG-MTC AB 1487 Ad Hoc Committee. Again, the request was not to create a new regional entity but “to rely upon the existing governance structures, strengths, and areas of expertise of MTC and ABAG.” The ad hoc group further proposed that the ABAG Executive Board and MTC share decision-making responsibilities for

— “Developing ballot expenditure plan (including setting tax rates and revenue sources, setting minimum; shares for 3Ps, criteria, potentially minimum shares at county level)”

— Project selection/programming of funds for specific purposes

— Commercial linkage fee nexus study and expenditure plan

Responsibility for “placement of measure on ballot” and “Financial administration (including collecting revenue, authorizing payments and issuing bonds)” was delegated to MTC.

The Ad Hoc AB 1487 Committee recommended three changes to the revenue allocations specified in the July 3 draft:

— Lower production allocation from 60 to 50 percent.

— Eliminate caps.

— Retain flexibility in bill now to modify the regionwide 3P shares (subject to board action and 30 day notice), but require a 55 percent vote requirement of both bodies to make changes.

The Ad Hoc AB 1487 Committee further recommended drawing a distinction between distributing monies from an employer head tax and from the other taxes in the bill, asking that at least 50 percent of head tax revenues remain in the county of origin based on revenue, leaving up to 50 percent available to be spent regionwide. Other taxes in the bill should be distributed so that at least 75 percent of the revenue goes to the county of origin based on revenue, leaving at least up to 25 percent for a regional fund. The Ad Hoc Committee wanted to “broaden where the [commercial linkage] fee revenue can be spent, not just in [the] local jurisdiction where it was imposed), consistent with whatever [the] legal nexus study determines.”

Furthermore, county share funds should be administered at the county level—“with one big exception—big cities.” The details of that exception are worth citing in full:

For the first five years, the four biggest cities in the region [Fremont is Number Four] should get a direct allocation of their county’s share based on their share of the county’s RHNA their share of the county’s RHNA. This can be extended at the option of the ABAG EB and MTC. Counties may want to also use RHNA in some manner for distributing within their county, but the bill should not mandate a formula distribution for smaller cities, as this could result in funds not being put to use as efficiently as on a first-come, first-served basis for qualifying projects within each county.

In other words, the four biggest cities would be guaranteed funding; the others would have to get in line.

Finally, the Ad Hoc Committee recommended removing the land acquisition and assembly authorization from the bill, “since neither MTC nor ABAG have experience or skill set in this regard. The regional funds can instead help support local agencies which do have such expertise.” Goodbye, regional land bank.

July 18: Professedly seeking to check MTC’s power, ABAG Ex. Board supports AB 1487 if further amended

On July 18, the ABAG Ex. Board voted 22-3-1 to support AB 1487, if amended as recommended by the two Legislation Committees and the Ad Hoc Committee, and as follows:

— Change the Ad Hoc Committee’s recommendations to direct automatic allocations to the three, rather than the four, biggest cities in the region.

— Add language to the findings portion of the bill acknowledging the severe imbalance between jobs and housing and the intent for the funding in the bill to address this problem.

— Modify the governance portion of the bill to require that ABAG be the “lead” agency by requiring that where action of both ABAG and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission is required, the ABAG Executive Board acts before MTC acts; and, should there be any difference in the subsequent action by MTC, the ABAG Executive Board would have to confirm that change through affirmative approval action; and, if the actions are in alignment, no subsequent action by the ABAG Executive Board is required.

These amendments, particularly the last, reflect ABAG’s effort to check MTC’s mission creep. Indeed, readers may have been wondering what business the Metropolitan Transportation Commission has in formulating housing policy in the first place. Good question.

MTC is a state agency created by California Legislature and, as the region’s Metropolitan Planning Organization, the designated conduit for federal government’s designated conduit for federal transportation funds. It administers more than $2 billion a year in mostly public funds, including more than $600 million in bridge tolls, for the operation, maintenance, and expansion of the Bay Area’s surface transportation network. Its 21-member board is dominated by the three biggest cities of the region.

ABAG is a voluntary association of the Bay Area’s cities and counties. It is the poor relation of the duo, subsisting on its members’ voluntary donations, grants, and MTC’s largesse, such as it is.

In 2016, with the collusion of ABAG Executive Board leadership, MTC engineered a hostile takeover of ABAG that resulted in the merging of the two agencies’ staff. That seizure signaled MTC’s ambition to become a one-stop regional planning agency that oversees transportation and land use planning for the region. Since then, ABAG has gotten its services from MTC staff via a contract with the MTC board. MTC’s surreptitious convening, oversight, and funding of CASA, the Committee to House the Bay Area, a process in which ABAG had virtually no say, was a second major offensive in the transportation agency’s quest for dominance. As the ABAG Executive Board tacitly recognized, AB 1487—itself a product of CASA—could further extend MTC’s sway.

The July 11 version of the bill retains language from the July 3 draft that arguably puts MTC in the driver’s seat of the Bay Area Housing Finance Authority. The text says “[t]he authority shall be governed by the same board that governs the Metropolitan Transportation Commission” and “staffed by the existing staff of the Metropolitan Transportation Commission or any successor agency, with the understanding that additional staff with expertise in affordable housing finance will be needed to administer the funding authorized in this chapter.”

At the same time, however, the July 11 version of AB 1487 also says that the Authority’s projects shall be “review[ed] and “approve[d]” by its “executive board….prior to review, approval and allocation by the authority”; and that “’Executive board’ means the executive board of the Association of Bay Area Governments.” Huh?

The ABAG Ex. Board’s third amendment sought to untangle the governance conundrum and make MTC the subordinate partner in BAHFA. Curiously, nobody on the Ex. Board said anything about removing the passage in the bill about the regional housing finance authority being governed by the same board that governs MTC.

Moreover, as per the Ad Hoc Committee’s recommendations, Chiu presumably agreed to give MTC the “responsibility”—translation: the authority—to place revenue measures on the ballot, to collect revenue, authorize payments, and issue bonds, all in behalf of housing. Whoever holds the purse strings holds the real power. Here’s another question that didn’t come up, at least not publicly: If MTC alone is authorized to place revenue measures on the ballot, will ABAG have acquired taxing authority? And something else that nobody remarked at the ABAG board meeting: MTC currently lacks the authority to directly fund housing; ABAG 1498 would give it that authority. That would be a major step in the agency’s drive to oversee transportation andhousing for the Bay Area. Perhaps that’s why on July 24, the MTC board approved the amendment without discussion.

The other two proposed amendments more subtly express ABAG resistance to MTC encroachment. The MTC board is dominated by the region’s three biggest cities; automatically guaranteeing allocations to the region’s four biggest cities, as recommended by Ad Hoc Committee, would extend Big City dominance; cutting the number to three counters, albeit weakly, that extension. Requiring that AB 1487 acknowledge and address the Bay Area’s severe job-housing balance tacitly recognizes that the region’s tech towns, including San Francisco, have approved enormous amounts of new office space but nowhere nearly enough housing for the people who will work—indeed, thousands of whom are already working—in such offices; and the resentment of other cities that are being asked to compensate for that dereliction by approving housing to accommodate those office workers.

Chiu refuses to make AB 1487 a two-year bill

In the story being purveyed by Chiu, his office, the CZI/ECP operatives, and the leaders of both MTC and ABAG, the Assemblymember appears as a collaborative legislator eager to hear out local Bay Area officials and to amend AB 1487 accordingly. At the ABAG Ex. Board’s July 18 meeting, Clayton Councilmember Julie Pierce gushed, “This is one of the most gratifying experiences we’ve had. Our assemblymember has been willing to hear every concern that we’ve had.” As a member of the Ad Hoc Committee and the ABAG Legislation Committee, Pierce had been deeply involved in negotiations with Chiu.

The local officials on the MTC and ABAG boards in turn come across as conscientious defenders of their constituents’ interests and the prerogatives of the regional agencies that purportedly represent those interests.

Both characterizations are questionable. For all his purported tractability, Chiu has dug in his heels in opposition to a key issue: making AB 1487 a two-year bill that the Legislature would take up again in 2020. The MOU that instituted MTC’s 2016 administrative takeover of ABAG left the question of governance unresolved. The agencies’ two staffs have been consolidated, but the two boards proceed as independent entities operating under different statutory terms. The MOU requires the governance issue to be decided by next July.

AB 1487’s Section 605410(e), which survived the July 10 gutting, hints at this volatile situation: “It is the intent of the Legislature that the entity be staffed by the existing staff of the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and the Association of Bay Area Governments, or any successor agency…”

Beginning this spring, and continuing through the most recent meetings at Bay Metro, numerous Bay Area city officials have argued that since the governance of ABAG and MTC may well be profoundly altered in a year, seeking state authorization for a major new regional entity is ill-timed. Why not delay the final revisions to and passage of AB 1487 until 2020, when the governance arrangements between MTC and ABAG will have been decided?

Here’s why: Chiu and the rest of the CASA cabal see the 2020 general election as a signal opportunity to put a revenue measure, if not two—one for housing and a companion for transportation—on a regional ballot. Indeed, the campaign for a 2020 $100 billion regional transportation revenue measure, “Faster Bay Area,” has already been kicked off by the Bay Area Council, the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, and SPUR. Both measures require state legislation giving a regional agency taxing authority, just as Regional Measure 3, levied by MTC in 2018, had to be authorized by SB 595; and Measure AA, levied by the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority in 2016, had to be authorized by AB 746.

Chiu says that waiting until 2020 to pass AB 1487 would be too late to mount an effective campaign. But that doesn’t seem to have fazed the corporate power brokers pushing “Faster Bay Area.” According to the Chronicle, the “initial bill” enabling the transportation measure “would have to pass early next year;” no such bill was introduced in the Legislature’s current session. Why, then, the rush to enact AB 1487 in 2019?

Technically, there’s no good reason, so the rationale has to be political. We can assume that a 2020 regional transportation revenue measure would be levied by MTC. If the measure turns out to be a 1 percent sales tax, as the Chronicle suggests it might, there’s likely to be opposition from local officials. But the governance issue would not be contested by MTC. On the contrary. By contrast, governance of MTC and ABAG itself remains a contentious matter.

In light of that contentiousness, the sooner a law authorizing the creation of a Bay Area housing finance authority is enacted, the better—and all the more so, given signs that the economy is softening, a development that augurs poorly for voter approval of new taxes. Go for certainty, at least in the legislative sphere.

Free lunch or poisoned carrot?

The leaders of ABAG, for their part, are also going for certainty—the certainty of housing funds for at least some Bay Area jurisdictions. At the July 10 hearing at the Senate Governance and Finance Committee, ABAG Vice President, member of the Ad Hoc AB 1487 Committee, and Berkeley Mayor Jesse Arreguín joined Enterprise’s Geeta Rao as one of the two supporters of AB 1487 seated at the table before the Senate committee. Arreguín put the money issue front and center. “The medium- and small-sized cities in the Bay Area,” he said, “desperately need additional resources to preserve existing housing, protect tenants from displacement, and build new affordable housing. That’s why AB 1487 is so important…”

Following up on Arreguín, Rao said: “Right now, we rely on local jurisdictions to solve the regional housing crisis.” That’s not realistic. Rendered “anemic after the dissolution of redevelopment,” cities and counties lack the requisite funding, staffing, and expertise—all of which AB 1487 would provide. And, not the least of the bill’s attractions: “It’s all carrot.”

At the May 16 meeting of the ABAG Ex. Board, Rao elaborated on the bill’s free lunch aspect:

This bill is all carrots: it’s money, it’s funding, it’s help with land assembly and data tracking. There is no sticks of land use authority or eminent domain. So many of you know that your housing departments have been gutted post-redevelopment. And we know this, because we [Enterprise Community Partners] spend so much time with your housing departments trying to help…with building a pipeline of affordable homes and creating protections, and so what this bill does is provide those resources.

Just in case the ABAG reps needed a bit more reassurance about their authority, Rao wheedled further:

The author has made so many amendments around the governance issue. It’s been punted until 2020, so you can still work on merging your boards, and you can create HABA, the Housing Alliance for the Bay Area, it can go away, once those board structures have been merged. [Note: it’s unclear whether those board structures will be merged or whether the MTC and ABAG seek such a merger.]

This sounds too good to be true, and as with most things of this sort, it is. The price of acquiescence is already apparent in the retention of the MTC board as the finance authority’s governing board and as the entity holding its purse strings. What remains to be seen is what else the newly amended AB 1487 will exact from local jurisdictions in return for the promise of money.

Much of the talk at the ABAG Ex. Board about amending various revenue options suggested that the revenue sections of the bill, which were wholly deleted on July 11, are going to reappear in some form in the draft that the Senate Appropriations Committee will consider in August. when Hayward Mayor Barbara Halliday asked if “the distribution” issue would “be in the final bill,” ABAG President and “The bill in front of us is a work in progress,” said ABAG President and Sonoma County Supervisor David Rabbitt at the ABAG Ex. Board’s July 18 meeting. “It’s going to change until the last minute.”

If certain provisions in the July 3 text of the bill—provisions that were not publicly flagged by ABAG-MTC staff, the Ad Hoc Committee, the ABAG MTC Joint Legislation Committee, the ABAG Ex. Board or the MTC board—are reinstated and enacted into law, they will further erode local authority over land use.

The governance sticks

Commenting on AB 1487 at SPUR’s July 16 lunchtime forum on “The State of Housing at the State,” Chiu asserted, “We’re not talking about changing land use or zoning.”

Really? It’s true that AB 1487’s Section 64522, deleted on July 11, stated that “the authority shall not…[r]egulate or enforce local land use decisions” (Section 64522). But in my reading, that section authorized the regional housing finance entity to enact and implement regionwide zoning, which is to say, to override local land use prerogatives.

On June 5, I emailed Chiu’s staff, noting that passages in AB 1487 seem to grant the entity regulatory, if not enforcement, authority over land use decisions. Under “Chapter 3. Expenditures,” for example, Section 64650(a), also deleted on July 11, along with the rest of the “Expenditures” chapter, stated that revenues allocated by HABA (now BAHFA) would serve “as an incentive to achieve affordable housing benchmarks established by the entity.”

Establishing benchmarks sounds like regulatory authority to me. Housing benchmarks presumably refers to the state-mandated Regional Housing Needs Allocations; RHNAs are all about zoning for housing. And jurisdictions that are not meeting their RHNAs—and virtually none are—will presumably be ineligible for funding. Doesn’t that fall under enforcement?

Section 64650 also listed the allocations by percentage according to which the housing finance entity “shall distribute the revenues” it gets from “any special tax…and the proceeds of bonds” for five years after revenue is approved by voters. Section 646509(a)(2), also deleted on July 11, stated that “[t]he entity shall change distribution requirements…if it adopts a finding…that the region’s needs differ from those requirements.” How, I asked Chiu’s office, does that not fit the definition of regulatory authority?